Hadley Griggs and Sharon Knolle

Max Richter isn’t your average composer. Sure, he’s written plenty of dreamy film scores, but he’s also undertaken something a bit more complicated: an eight-hour composition meant to be listened to during a full night’s sleep.

Aptly titled Sleep, the album is quite a commitment to listen to—and even bigger of a commitment to perform live. But Richter and a group of performers have performed it several times, in continuous overnight concerts complete with cots set up for each audience member. One such performance, an open-air concert for 500 people in LA’s Grand Park, is the subject of a new documentary at the Festival: Max Richter’s Sleep.

Rather than a straightforward telling, Max Richter’s Sleep is a sumptuous dreamscape of Richter’s story with his creative and romantic partner, Yulia Mahr, interwoven between footage of the Grand Park performance and the whistling of wind through wheat. Director Natalie Johns explained, “It was a very vulnerable place for the audience, and [Yulia] and Max tried very hard to create a space that really was ‘space.’ That was something I wanted to capture, the guiding principle for how we approached the film.”

Max Richter was in attendance, and one audience member asked about his own experience with the music. “This piece is fraught with paradoxes for us,” he explained. “Because even though it’s about providing a space for relaxation, dream time—when you’re making it, it’s the opposite. It’s mostly about incredible exhaustion. It’s a little bit like when you have a tiny baby and you’re too tired to enjoy it; it’s only in retrospect you’re able to enjoy it.”

Another audience member asked if Richter himself uses the Sleep album at night. “I can’t sleep when there’s music on,” he laughed. “Because I’m working.”

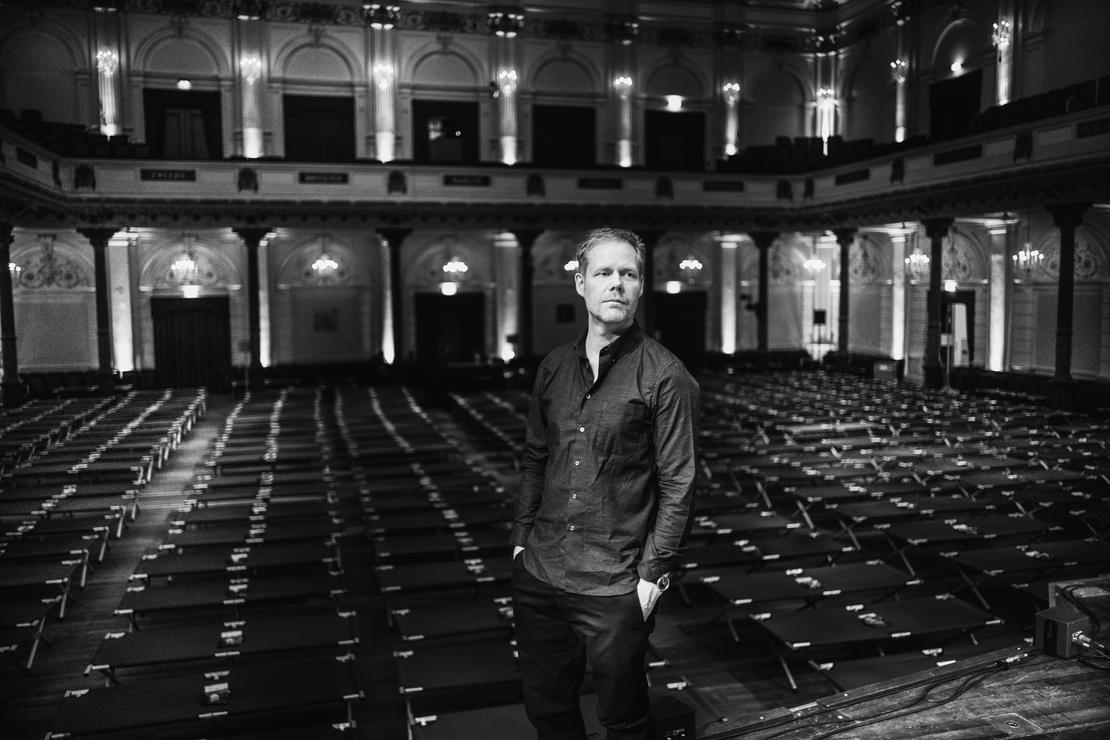

Max Richter at the premiere of ‘Max Richter’s Sleep.’ © 2020 Sundance Institute

Shooting during the concert presented difficulties of its own for the crew. “It was a challenge for sure,” said producer Oualid Mouaness. “The lighting levels were very low at the venue—intentionally, so that people could sleep. We had a strict policy of no additional lighting in the venue, so it was a lot of playing with shadow. We were shooting with really fast lenses, so the blur was inherent in the piece. We played with that, a lot of silhouette, a lot of flares to get that look.”

“The first two hours of the shoot were the most tense,” he said. But then something interesting happened. “As the music started, the entire crew seemed to mellow out. The entire tone of the shoot ended up being quite beautiful.”

Johns added, “Normally when you’re shooting, you’re working on a tight schedule—you have a certain hour with someone. We had eight and a half hours of music to shoot. And so you have to keep reinventing your shots. You’re gonna get bored with your image, so you get more and more experimental as the night goes on. That’s when you start to see these beautiful, abstract, extremely long focus pulls where everybody’s just completely sunk in and become enchanted with the music.”

The documentary wasn’t all that Richter was doing at the Festival. Later that evening, he performed a live, 90-minute concert version of Sleep with a string quintet from New York’s American Contemporary Music Ensemble. While most of the audience sat attentively in chairs, couches and rugs set up on the sides allowed attendees to drift off or actually fall asleep during the performance.

In a Q&A afterward, Richter acknowledged that people use the piece in many ways after someone shared that they’d written a short film while listening to it: “Some people have used it for sleeping, others use it for writing or for ante-natal care or palliative or end-of-life care. I really like the idea of artwork having utility. There’s an element to creativity that is a sort of cognitive tool to unlock things, to reframe things, to change our perceptions in some ways. That’s what music and creativity are, to change the way we encounter the world.”

One man asked the lead cellist, Clarice Jensen, if she got into a “drone” state while playing, similar to how he does when he’s running, or if instead she stays hyper-focused. “It’s both,” she replied. “I think all of us lose ourselves and lose track of time due to especially the repetitive nature of the notes and the economy of the material—the first cello solo is a D-flat 17 times, and the entire melody is four notes. I guess you get hyper-vigilant about creating each note perfectly, so you use everything inside of you. I don’t run, but maybe it’s similar. You are putting one foot in front of the other over and over again, so the expression comes from the same motion.”

In comparing the 90-minute concert to the full-length performance, Richter said, “It feels like we put eight hours of energy into the 90 minutes, it’s so different. Because the audience is [really] listening rather than just in this other place.”