The Overnighters

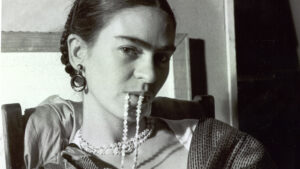

Tabitha Jackson

From Iraqi role-players to a demolition derby driver to an Ivy League impostor—provocative, unique, and emotionally compelling characters have always been central to Jesse Moss’s storytelling. The latest film by this award-winning documentary filmmaker and cinematographer is no exception. The Overnighters, which recently premiered at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival and was awarded the Special Jury Prize for Intuitive Filmmaking, follows a Lutheran pastor in the oil boomtown of Williston, North Dakota. Moss spent 18 months shooting in and around Pastor Jay Reinke’s Concordia Lutheran Church to capture a truly intimate story full of electrifying moments. Reflecting on how a small human story can transform into a riveting drama, Moss discusses the “revolutionary emotion” of empathy with Tabitha Jackson, the Director of Sundance Institute’s Documentary Film Program.

Tabitha Jackson: How did you get into filmmaking?

Jesse Moss: I met Christine Choy, who is a documentary filmmaker. At the time I was working in politics, and she came and showed a film called Who Killed Vincent Chin? I had been interested in journalism but hadn’t pursued that path, and I had been interested in politics and I pursued that path. And when I saw her film, I thought, “Wow, documentary filmmaking can be journalism. It can be political. It can be artistic. And I don’t know if I can do it, but maybe I can try.”

That year, 1994, there were two really influential documentaries that came out: Hoop Dreams and The War Room. I saw both in the theater. That was also a new experience for me – seeing nonfiction filmmaking that felt like it had the power, the force, of fiction, was eye-opening. That also inspired my interest in documentaries. So, Christine lived in New York City at the time, and I was living in Washington, D.C., and I said, “Can I come work for you?” And she said, “Sure. I can’t really pay you anything. But you can work on this film.” So I quit my job impulsively and I moved to New York, and I went to work for her on a film and haven’t looked back.

TJ: That’s amazing. I, too, had that experience of watching Hoop Dreams in a cinema and thinking, “This is incredible.” Did you have any sense of what kind of stories you wanted to tell?

JM: Well, I think even in that very first film that I worked on, Christine’s film, there was a storytelling that has been a through line in my own work – character-driven, and asking timely, provocative questions about our culture, about our politics, about the world we live in, but through a narrow, human-scale story. And in this case, it was a film about a Japanese exchange student who had been shot and killed by a homeowner in Louisiana, where it was considered to be justifiable homicide. What Christine was doing, and what really has always interested me, was getting inside the small human story that might have been a blip in the newspaper. But actually, when you really brought a lens to it and patience and artistry, it became an incredible human drama.

Then I went to work for Barbara Kopple, and inspired by her work Harlan County USA and American Dream, I began to think about making films that, like Hoop Dreams and The War Room, were told in the present tense. Christine’s film was kind of a forensic analysis of this crime. But Barbara’s work was also really influential and also political. I thought, “I don’t really know how you make films like this. I can learn something by working for Barbara,” which I did.

TJ: Can I ask what you learned?

JM: The lessons were very subtle in some ways. I didn’t really know anything about filmmaking, and I didn’t actually learn anything about the technical side of filmmaking. But what I learned from Barbara was, first of all, a kind of spirit that is evident in her as a person and in her work with people, and tenacity, which I saw in the field during production. She is an incredibly warm, nice person, and trusting of someone like me, who was kind of coming from nowhere, but also incredibly strong and determined and focused in her work. I saw how hard and tough you need to be when you’re making your movie, and how much will work against you. When I think about Barbara’s lesson to me, it’s fortitude. It’s fortitude that’s expressed in her work that she had made long before I went to work for her. She had a bravery in going to places, to unfamiliar communities, and to homes, with an empathy for people that was very inspiring.

TJ: Let’s talk about empathy for a bit, because for me, that’s what Hoop Dreams unlocked: that realization of the power of empathy. And for me now, that is the power of documentary, and why I enjoy the medium so much – that it can act as a kind of empathy machine, but also a time machine. It can take you all around the world into these communities. I want to peddle empathy and have it be something that we’re exporting through documentary. I can’t remember who said it, but someone said, “Empathy is the most revolutionary emotion.” It feels like for change to happen, you need to understand what it might feel like to be on the other side. How do you value empathy as a motivation or force in what you’re doing, or is something else going on for you when you tell stories?

JM: Yeah, well that’s motivated my work. Fortunately, the camera affords that privilege to make a journey from my fairly comfortable, secure position in a community in which my views tend to be reinforced by everybody around me to a place that feels very different, be it a community or a life, a home, a country. I’ve always – and sometimes to a fault – embraced making that journey to the other side. For me, that comes from a set of questions and concerns about the world, because you can go with relatively little baggage as a documentary filmmaker – for me in Williston, I came alone, literally no apparatus. And it allows you to slip pretty easily into that place and…

TJ: And Williston, North Dakota, is the setting of your latest film, The Overnighters?

JM: Yeah. For me, whether it was the world of this racetrack on Long Island where I shot my first movie, which is so different from my world, or the Army’s Iraq War training simulation, I think maybe there’s something a little bit provocative about going to these places sometimes. They’re alien, I guess. Often these weren’t particularly politically motivated journeys, but I guess I react to the polarization of this country and feel like one thing I can do is to travel to the other side and to film what I see. I think hopefully what I see might be uncomfortably gray or complicated, but if it is drawn with humanity and empathy and compassion, there’s a universality that hopefully will bring us all there.

TJ: Can we talk a bit about your process? What’s the very beginning of the process for you?

JM: I’m in some ways a very slow starter and in some ways a very quick starter, and my wife would say I’m terrible at starting projects. It’s harder the older you get – the more you poo-poo and you second guess and question the commercial liability of projects. The more you know, the harder it becomes in some ways, even though it should be easier, right? But once I say, “OK, I’m going to go and see what’s here,” I just like to start and to shoot. And that’s the freedom that comes from shooting myself, which is there’s no need to wait for anything. I do like to write about what I’m interested in in the form of a treatment pretty early on.

TJ: Do you write it as a story?

JM: I write it as a treatment. So it could be a few pages. It’s both the ideas and the story. But I like to just shoot. I don’t play music, but it feels to me as close as I’ll get to playing music, where I can just be in the moment. I like to do that and to see: What do people look like on camera? How do they respond in front of the camera? What do they reveal about themselves? And that’s my process.

TJ: How long would you typically envisage spending with a character in order to make a film? What’s your comfortable production length, given all the constraints of budget and availability?

JM: I feel like I could just keep shooting forever. One film I made had an arbitrarily imposed constraint: The event took place over three weeks. Beyond that, we did go back and do some follow up filming, but really it was principal photography. It was like fiction: There is principal photography, and then you’re done.

TJ: I just got back from China, and the issues with the Chinese filmmakers –Taiwanese filmmakers, American, British filmmakers, independent filmmakers –are very similar. They translate. Often it is about: How do you know when to stop shooting? How do you know when you’ve finished your film? Sometimes you don’t know you’ve finished your film until you get into the edit. So that’s not very helpful when you’re shooting.

JM: Sometimes, you get into a film festival and then you’re done. That was a big question with this film.

TJ: The Overnighters?

JM: Yeah. I had trouble deciding when The Overnighters was over on one hand, because I ended the film in the midst of incredible turmoil in my character’s life. On the other hand, I knew exactly when the film should end, because the moment I shot the shot, I said, “That’s the last shot of this film.” It doesn’t mean there’s not an incredible story unfolding with the subject, but this film ends here.

TJ: What was that shot?

JM: It’s the pastor standing literally at the crossroads. It was sort of an accidental shot. I was up on the top of a car filming a church in Williston, N.D., and then out of the corner of my eye, I see him wander over to the road. And I just panned over. And he’s just alone, and that’s where he’s left in the film. He was geographically isolated in the frame, and he was looking at an oil rig. It’s actually two shots, but it’s a wide shot. And I just thought, “This is where this man’s story ends, right here in this shot.” But I love embracing the uncertainty of not knowing, actually, where the story ends and feeling pretty confident that we’ll find it and maybe it will be arbitrarily imposed because a festival will say, “Your film is finished and we want to take it,” or maybe it will be because we’ve reached that point. But I think what’s exciting about that kind of filmmaking for me is that it is longitudinal. You give yourself enough time if you have the resources and the patience to let life take its remarkable and unexpected course.

TJ: Do you use a sound recordist?

JM: I do sound myself.

TJ: So it’s an incredibly intimate and intense connection that you have with your subjects. When you edit, do you use an editor?

JM: I do. I really need to because I’m alone and I have that intense relationship to the subject and to the material, so I think it’s all the more necessary to have a strong counterweight in the edit room who doesn’t have an emotional investment in any of the material but brings both editing talent and a rigorous impartiality. And I certainly bring my own investments – they get acted out in the process, and that’s healthy – but I need the counterweight. I do also think it’s very valuable for a filmmaker to edit themselves. The editing often takes a long time because of the specifics of funding, and people get fatigued, editors leave projects, you run out of gas, you pause, you go back, you shoot. So in those interim periods, I always end up with my movie or part of my movie on a stack of drives in my living room, looking at it thinking, “What the hell is wrong with this film?” or “Where does this need to go?” And being able to cut scenes is really important for me.

TJ: Yeah, I was just with Werner Herzog’s editor, Joe Bini, recently, and he was saying the same thing. He was saying anybody involved in film should learn how to edit, not because they should all edit their own films, but because it’s a language and there’s a grammar. Now you can just do it on your laptop. Learn the language and then you can speak the language more usefully, perhaps, to the editor.

JM: Yeah, I think owning the means of production is essential for a certain kind of work. I mean, I have always enjoyed my collaborations in production with cinematographers, and in some ways I would never represent myself as a cinematographer that one ought to hire, even though I’ve done a little bit of that. But I just feel like the freedoms that come from owning the equipment and having the wherewithal to use that equipment allows for risk. For me at least, the most rewarding, successful work has been the work that I have made with the most amount of freedom. So that means typically by myself without having to concern myself with what other people think about my subject or the story, or whether they’re tired and they need to go back to the hotel room, or whether they’re just bored. I get to surrender myself entirely to that experience.

TJ: Do you see the role of the documentary filmmaker to be an objective witness to things?

JM: The work is both objective and subjective, and I think the role is both. And that’s the power of the medium, because it is a combination of camera witness and human relationship with your subject. And sometimes it’s intense and profound. You can’t run from it, you can’t hide from it. It overtakes you, sometimes in ways that are really complicated. And that’s not a bad thing. In a way, that is both what makes the work powerful but also moves it from objectivity to subjectivity. How you negotiate it personally and professionally and within the frame itself is such a fluid process, and a fraught and challenging process. I still feel like I’m unpacking that and negotiating that in The Overnighters. And I think the wonderfully liberating but also challenging thing about documentary is that there is no set of rules. If you work at The New York Times there’s a code; there is a style template for how you say certain words. And there’s also [an established] code of ethics. And documentary is sort of perilous in that it’s one’s own sense of ethical boundaries, one’s own sense of common decency to guide you.

TJ: I think there is a sense of documentary ethics, this imbued sense within the community. But yes, there are these individual relationships, and it feels like that’s perhaps why it’s perilous making a documentary. But it’s also perilous being a subject in a documentary, particularly now with the ubiquity of social media: People can say anything about anyone. The ease with which people can now see documentaries means that there are interesting questions to be asked about the responsibilities of documentary filmmakers toward their subjects. Any thoughts on that?

JM: I’ve never had to think harder about that question than I have in the last six months making this film, and taking it out into the world, and with my subject, and all of the complications in his life, and his relationship and his family’s relationship to the film. Those are often competing interests. What you discover is that, first of all, what may be your legal right with regard to your film and your subject is not necessarily the moral right. And where your interests as a filmmaker may align for a long period of time with the interests of your subject, there may be a point at which those interests diverge. And how do you decide where your obligations lie as a filmmaker? As a human being? I have done some work in public health in which, when you work on a federally funded public health research project, there are strict guidelines about human behavior research. And I’m conscious of the fact that they don’t exist in documentary film, for better and for worse. Yet you are in a position to shine a harsh light on somebody’s private life, for better and sometimes, perhaps, for worse. And one of the questions I’ve been considering is the power of film to find the story with this person who is not well known, not a public figure, and to bring their story to the attention of the world – or the small corner of the world that we in documentary film occupy.