By Nick Joyner

“Todd Haynes’s Poison is a vision of unrelenting, febrile darkness.” Thus opens Hal Hinson’s 1991 damnation of the film in The Washington Post. Hinson was right — sort of. The film is about darkness, but that’s hardly negative. Perhaps darkness is Poison’s guiding light. Darkness and its attendant themes do not poison a film’s glow, but rather they add the contrast necessary to see its contours of desire. One wishes Hinson might have plumbed the depths of this gloom to discover Poison’s otherworldly logics, where there is hope in suffering and pride in shame.

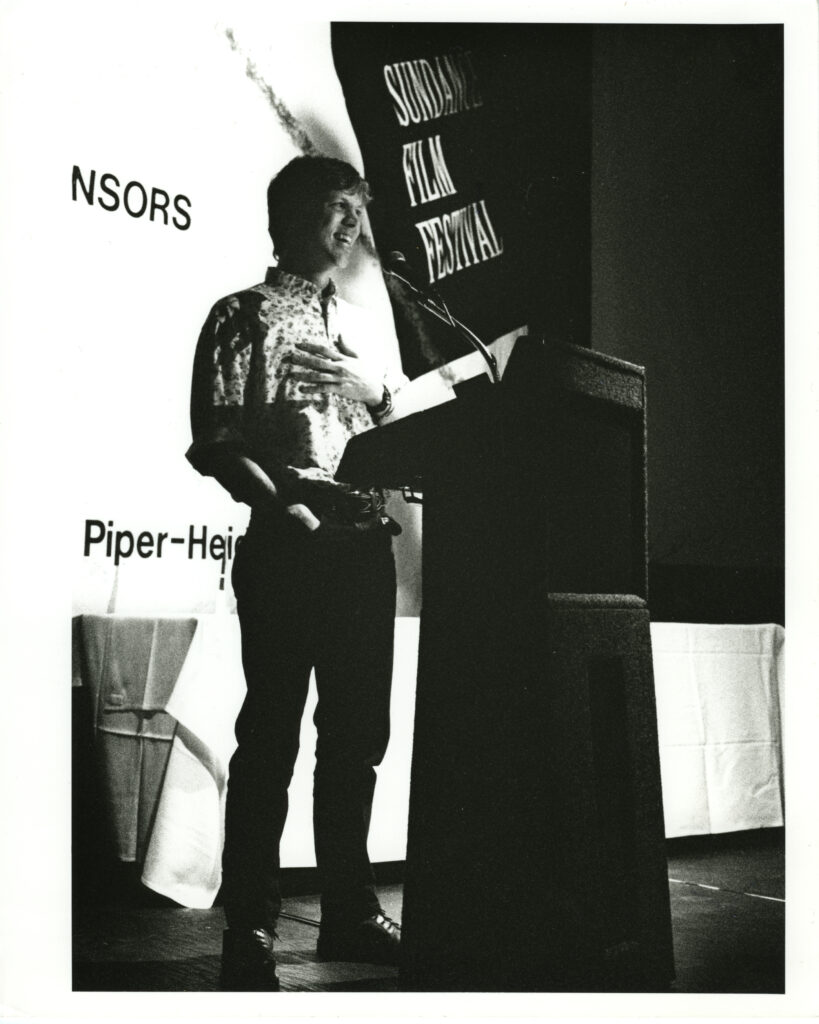

Poison is a formal and political triumph, and over 30 years later, it remains the most audacious film to win the Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic at the Sundance Film Festival. Today, its luminance is often overshadowed by the controversy surrounding its federal funding and the historiographic conversations about New Queer Cinema, conversations that would rather relegate the film to “torchbearer” status than recognize it as an arrival in its own right. Viewed today, Poison still retains its same power to shock and awe, especially given how much of modern queer cinema has doubled back on the trails that Haynes blazed for them.

Released in 1991, writer-director Todd Haynes’ first feature was a formal exercise in upending traditional “straight” film language. It features three non-overlapping storylines — “Hero,” “Horror,” and “Homo” — told in chronological order and intercut every few minutes. The threads themselves explore different pathologized outsiders who are grappling with forms of interpersonal or societal violence. They are victims of citizen surveillance, suburban mistrust, medical injustice, carceral punishment, and the like.

“Hero” appears to be a straightforward television documentary about a patricidal schoolboy named Richie Beacon, whose disappearance turns into a cerebral Freudian tale. His ditsy, fundamentalist mother maintains that Richie shot his father and “flew” out the bedroom window, while his classmates and school administrators mutter about a perplexing child who seemed to provoke and enjoy physical harm. “Horror” is black-and-white sci-fi schlock à la Carnival of Souls that follows a scientist — Dr. Thomas Graves — who mistakenly drinks the essence of human sex drive. This mini monster movie can most clearly and obviously be read as an allegory for the AIDS crisis, as it follows a “leper sex killer” whose kisses leave deadly lesions. It is perhaps the least subtle of the three, but a fun genre play nonetheless. And then there’s “Homo,” an elegiac look at the life of lifelong convict John Broom. The present timeline follows his admission into a penitentiary in the 1940s, where he encounters an old acquaintance and slips into an obsessive rêverie about their homoerotic years in child detention.

As the film progresses, the boundaries within the triptych blur, the subjects begin to interlace, and new meaning is created between each of the stories. It conjures incompletion; as the narrative strands intercut more frequently and converge in the film’s back end, the audience is encouraged to read across — rather than within — each thread for meaning. This was Haynes’ experiment: to call into question the conventional modes of heterosexual filmmaking itself, freely rejecting causal relationships, narrative closure, and inherent objective meaning, those age-old guides that critics like Hal Hinson would cling to. It is a film that staunchly believes that the political is inseparable from the aesthetic, that the two are mutually constructed.

Though Poison rejects conventional storytelling, it embraces genre with outstretched arms. It plays with generic tropes, adopting and working within them instead of subverting them outright. Rather than deconstructing 60 Minutes–style newscasts (“Hero”) and B movies (“Horror”), Haynes obeys their cinematographic conventions, turning them into Trojan horses for denser literary and psychoanalytic explorations. And in “Homo,” a loose adaptation of Jean Genet’s 1946 book Miracle of the Rose, Haynes plays up the fantastical melodrama with intentionally stagey set designs.

Genet is not confined just to this thread; the entire film — true-crime special, monster movie, and prison diary — is suffused with his ideas and writings. And Genet’s work contextualizes Haynes’ “febrile darkness” in no uncertain terms. Sandwiched between the final shot and the closing credits is a direct quote from Genet’s novel Funeral Rites: “A man must dream a long time in order to act with grandeur, and dreaming is nursed in darkness.” Darkness, then, is a generative force. And one must dwell within it before achieving bliss. Thus was Haynes’ project with Poison: spinning feverish lugubriosity into something sublime.

Beyond its narrative experimentation, Poison is a capital Q Queer film for the way it illuminates the darker sides of homosexual life and politics, of the more unsettling experiences and desires that, to date, had gone unprobed. Haynes is most interested in the linkages between deviancy, violence, disgust, and pleasure and how queerness entangles itself at these junctures. At times, it can be unpleasant, but it never feels untruthful. Poison is about queerness as the ultimate form of transgression. Like Genet, Haynes embraced this conflation of homosexuality as criminality; he took pleasure in being labeled deviant. As Haynes explained in a 1993 interview, “Genet wrote about a strangely united political and erotic charge that he experienced with regard to homosexuality that was violent, that was based on upsetting the norm and not about finding a nice safe space that society will give you.” For Haynes, exclusion is a method of survival, submission a means of control.

Haynes was not interested in making films about simple victims who fell prey to the violences of a homophobic society. Here are characters who are imprisoned but not broken, abused but not powerless, cast aside but not ashamed. They could name their suffering and learn from it without losing track of their desires to revisit or re-enact these sources of violence or punishment. The film is not about surrender, resignation, or quiet disobedience. It’s about transforming oppression into something far more fantastical, pleasurable, and ostentatious: power. James Baldwin put it best in a quote that Haynes paraphrased in an interview: “The victim who is able to articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be a victim: he or she has become a threat.”

Today, Poison is known in equal measure for the scandal and commendation it elicited upon its premiere and subsequent release. In cinephilic circles, its Grand Jury Prize win signaled the overflow of avant-garde queer cinema into the mainstream, especially following a healthy showing of LGBT films at the previous year’s festival. Like other festival winners of the era, Poison could have easily enjoyed early critical acclaim before being largely ignored by the public. The film’s censure by the religious right, however, was what immortalized it for many. Because Haynes received $25,000 from the National Endowment for the Arts to complete the film, he found himself at the center of a debate about federal funding of the arts. After attending the NEA-sponsored screening of the film in Washington, D.C., Jim Smith, a spokesman for the Christian Life Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, quipped that he’d “seen more artistically meritorious productions on America’s Funniest Home Videos,” before slandering it as “perverse and denigrating and violent and homoerotic.” While a damnation to most, disobedient queers saw this as the highest form of praise.

The Motion Picture Association of America handed down its own form of praise, rating the film NC-17 for its “explicit sexuality,” and forbidding minors from seeing it in theaters. In comparison to its NC-17 bedfellows, Poison is remarkably tame in terms of nudity. Indeed, it was strange that a relatively sexless film could engender such revulsion. But perhaps it was not the unabashed homosexual that Poison’s detractors were afraid to see onscreen, but themselves. They are the sadistic bullies tormenting Richie Beacon, the vengeful mob hunting Dr. Graves, the prison guard detaining John Broom. Maybe they were less disgusted by the scene of reformatory boys spitting on another student than with the suggestion that they might be implicated in enacting the same violence depicted on screen. Knee-jerk outrage is a power smokescreen against admitting culpability, but thankfully, the moralistic hand-wringing helped sell tickets.

Perhaps a portion of Poison’s notoriety lies in its unwillingness to “play nice” and construct “good” representation for the gay community. But any representation — good or bad — would not have mattered to its contemporary critics. They were too outraged over a few choice scenes to even notice Haynes’ more high-minded experiment in making an actually queer film, not a movie about homosexual characters that was “straight” in structure. And it couldn’t care less if its characters were warm and fuzzy.

Over 30 years later, Poison continues to repudiate these “positive image” debates that would rather art morph into false social propaganda that peddles sanitized and digestible mistruths about homosexual life. Poison is about the power of refusal, of embracing exclusion, and of admitting that queerness can be a threat to the norm. It refuses integration, acceptance, and co-optation. It seeks to be a ragged outsider. It is a film about ruin and rot, how pleasure and degradation become intertwined, how transgression becomes transcendence. Cycles of violence are ended, pride overcomes the shame of illness moments before death, and showers of spit turn into rose petals. Just like Richie Beacon, Poison had wings. It was fearless, jumping from the tallest of heights. And boy, did it soar.