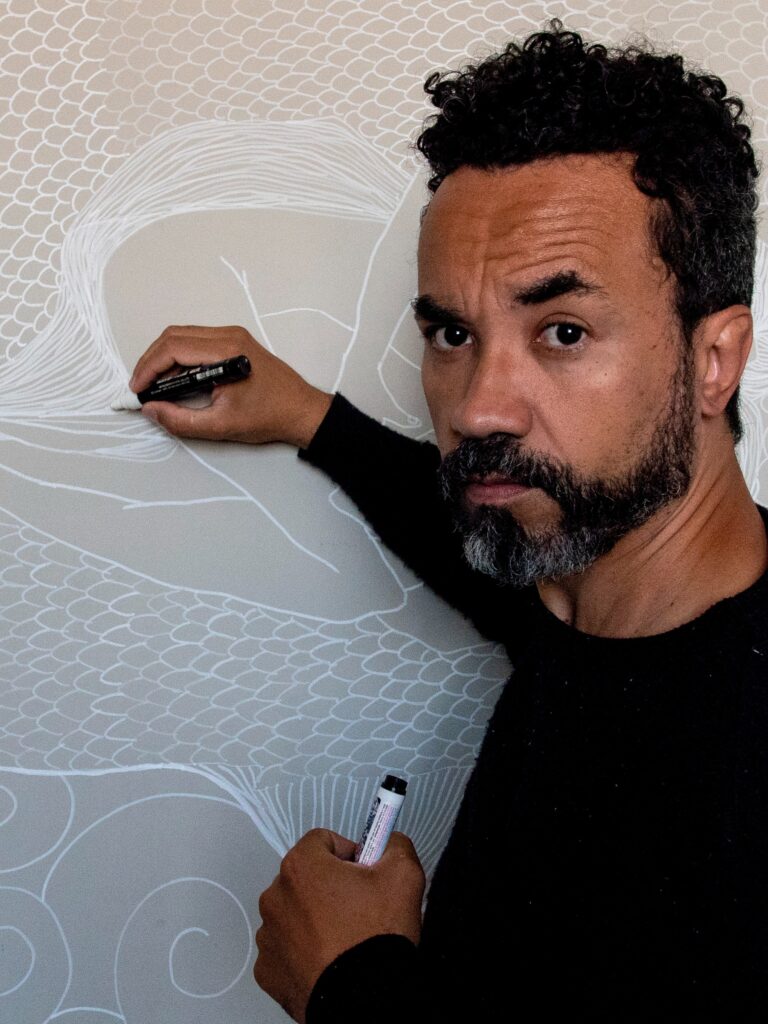

A still from Daniel Barosa’s “Boi de Conchas (The Shell Covered Ox),” which screened as part of Short Film Program 4 at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival.

By Lucy Spicer

One of the most exciting things about the Sundance Film Festival is having a front-row seat for the bright future of independent filmmaking. While we can learn a lot about the filmmakers from the 2024 Sundance Film Festival through the art that these storytellers share with us, there’s always more we can learn about them as people. This year, we decided to get to the bottom of those artistic wells with our ongoing series: Give Me the Backstory!

As we continue to celebrate Latine artists this September and October, we’re diving back into the 2024 Sundance Film Festival Program to revisit the varied projects by Latine filmmakers. The 2024 Festival lineup featured 17 such projects, including seven short films across four different programs. Below, we’ve compiled insights about four of these shorts and their filmmakers. Daniel Barosa (Boi de Conchas (The Shell Covered Ox)), Nico Casavecchia (Border Hopper), Catapreta (Dona Beatriz ÑSîmba Vita), and Margaux Susi (guts) drew from personal experiences, folklore, historical figures, and more to create nuanced and thought-provoking works with cinematic breadth — despite their short run times.

Exploring topics such as coming of age, immigration limbo, Afrocentric history, and eating disorders, these four filmmakers employ innovative uses of animation, genre-bending, magical realism, and more to craft stories that reflect their unique voices. Read on to learn more about four of the Latine filmmakers who brought their fascinating projects to the 2024 Sundance Film Festival Short Film Program.

What was the biggest inspiration behind this film?

Daniel Barosa (Boi de Conchas (The Shell Covered Ox)): My wife, whom I’ve been with for 18 years, was born in Bertioga, where we shot Boi de Conchas. Since we met each other in our late teens, we always visited the small fisherman town. I always wanted to film there and tell a story in this unique region located a few hours away from São Paulo, one of the biggest cities in the world. It wasn’t until the pandemic, when I found out that one of the nearby beaches was overrun by oxen, that the idea came to me. Coincidentally, I read about the folkloric Boi de Conchas manifestations soon after: a festivity in the region that tells the story of an ox that runs away to the ocean.

But long story short, my biggest inspiration is my wife and the place where she grew up and where our relationship evolved over the years.

Nico Casavecchia (Border Hopper): It all began in the mid-2020s. My wife, who is also my co-writer, and I found ourselves in what’s often referred to in immigration jargon as “green card limbo.” Our immigration status was approved, but the necessary documents were never issued, held up by a mix of Trump-era policies and pandemic-induced delays. Then, an urgent opportunity to film a project overseas came up, and I applied for an emergency travel permit, as people do in cases like this. The situation became so absurd and chaotic that we began jotting down notes for future use. It was evident that we were in the midst of an ordeal perfect for a film. We couldn’t settle on a genre — the situation oscillated between a horror movie, a comedy of errors, and an early 20th-century surrealist film.

As I prepared for the shoot, I kept coming back to Jim Henson’s Labyrinth, a film I used to watch obsessively as a kid. In the movie, Sarah, the protagonist, must endure a series of challenging trials thrown at her by Jareth (played by an über-’80s David Bowie) to emerge transformed. In Border Hopper, I aimed to strike a similar balance of darkness and whimsy in its tone. The mix media approach of our film, with its blend of live action and animation, comes from there. In the short, Laura is so desperate to assimilate into the system that she willingly endures a series of bizarre challenges akin to a video game, risking her very soul to become the ideal immigrant.

Catapreta (Dona Beatriz Ñsîmba Vita): The film is a free adaptation of the story of ÑSîmba Vita (Kimpa Vita), an African historical figure born in the Congo region who lived in the 17th century. ÑSîmba Vita was a political and religious leader regarded as a prophetess with magical and supernatural powers capable of performing miracles and astonishing feats. ÑSîmba Vita became a controversial figure persecuted by the Catholic Church during the Portuguese occupation of the Congo region.

Margaux Susi (guts): guts is inspired by the writer’s own experience in eating disorder recovery and the kindness of strangers (i.e., guardian angels) who have helped them stay on the beam. Recovery is not linear, and no two people have the exact same experience, but anyone who has time away from the cruel, frightening, and dangerous illness will tell you that their worst day in recovery is better than their best day when they were sick.

Films are lasting artistic legacies; what do you want yours to say?

Barosa: I want my films to give teen angst a new look. There is some wisdom in our teen years that we seem to forget over time. While shooting this short, I was amazed how this new generation (most of the film’s cast is barely 20) has a clear mindset about what matters in life, where one should spend their energy, and how to avoid toxic environments. Despite all the specific problems each generation faces — and these young people do have their share — we can learn from them.

I want older viewers to see my movies and say, “Wow, I never thought of that this way…” and I also want younger filmgoers to see my movies and say, “Yeah, I get that.” If my movies serve as a connection between generations, I’d feel fulfilled.

Catapreta: My wish is that the film sparks an interest in other historical figures, different references, both geographical and cultural, so that we can build an alternative understanding of our origins as a people and as a country. The history we learn in school is the history told from a Eurocentric white perspective, and the result is an erasure of our ancestry and a lack of real understanding of the origins of prejudice, racism, and income inequality.

If history is, in a way, a narrative invention based on a certain perspective, it is time for us to reclaim and invent other heroes and other enemies so that we can gain clarity on what we should preserve and what we should fight against in order to build a more egalitarian society.

Susi: I hope this film makes at least one person struggling with an eating disorder feel seen. I want them to feel like recovery is possible.

Describe who you want this film to reach.

Casavecchia: I hope to reach as broad an audience as possible and discover their reactions. As a filmmaker, it is impossible to experience the work for the first time, but watching with an audience is as close as it gets. I think people with an immigrant background will catch the inside jokes and relate to the experience. I hope the film bridges the gap and immerses all kinds of audiences in the wild roller coaster of absurdist immigration bureaucracy, which is quite a ride, let me tell you.

Catapreta: In addition to individuals who are tainted by intentional or passive disregard for the history of African and Latin American countries, I sincerely hope that this film reaches people, whether Black or nonwhite, who overlook the connection between racism and their own depreciated socioeconomic condition. Here in my country, many Black individuals have been ensnared by the idea that racial issues are unimportant or even corrosive and dangerous, responsible for dividing the nation. I believe the opposite; I think that Brazil has always been divided precisely because of racial issues, which separate poor Black individuals from wealthy white and privileged individuals in various ways.

Susi: It goes without saying that I hope the film reaches anyone who is struggling with disordered eating/body dysmorphia. I also hope this film reaches people who know someone who is struggling but might not know how to support them or what to say. Sometimes people just need to talk. Sometimes people need meal support. It doesn’t have to be a secretive recovery process.

Why does this story need to be told now?

Barosa: I believe this story shows an exacerbated version of our world. We can trace metaphors of concurrent problems through fiction. With Boi de Conchas, we’re giving voice to teens who lost so much in such a short time living in this world. This is a film about depression, grief and different ways to deal with it, and I think this is something always worth discussing.

Catapreta: To prevent the complete extinction of ancestral African culture in our country and in Africa. To ensure the perpetuation over time of figures like Dona Beatriz ÑSîmba Vita and thus, to open space for a real and honest critical sense about colonialism that still subjugates nations around the world today.

Susi: Eating disorders affect people of every age, race, size, gender identity, sexual orientation and background. 9% of the U.S. population, or 28.8 million Americans, will have an eating disorder in their lifetime. 35–57% of adolescent girls engage in crash dieting, fasting, self-induced vomiting, diet pills, or laxatives. I could go on and on. The statistics are horrifying. It can feel really helpless. All I can do is try to break the cycle with my own future children and make some art in hopes that it can reach one person struggling.

Tell us an anecdote about casting or working with your actors.

Barosa: To cast this film was challenging. The ending sequence demands a musician, someone with natural musical talent. While anyone can dub a bass solo, only a true musician (or someone with months of practice) will know how to understand a musical instrument. So, I decided that for the leading role, I’d seek musicians instead of professional actresses. That’s when I found Bebé. I had seen her concerts and knew of her talent, which is overwhelming, especially considering her young age. She did have some very brief experience acting, but the fact that she came in so fresh was beautiful because we could create a lot together from scratch. She gave it all, and I couldn’t be more proud and thankful to have her in the film.

As for the other young talent in the film, we decided to work with nonprofessional actresses and actors, focusing on people from Bertioga, the coastal town where we shot the short. They all frequented amateur theater provided by the state, and I have to say, they were so comfortable and sure of themselves in front of the camera that this has got to be the most efficient amateur theater school in the world. It was inspiring to see everyone just dive into the film, even though it was their first venture in cinema.

Catapreta: During production, our film was sanctified by the Nkisi, African deities worshiped in Brazil, through specific rituals that are better kept secret…

Susi: By the time we got to the wide shot of the actors at the dinner table, they’d already eaten so many PB&Js. Because of this, we only did one take in this set up. They both come from a theater background, so we treated it like a play and went through all 10 pages in one go. When you have brilliant actors like the legendary Kate Burton and the fearless Angela Giarratana, half your work is done for you.

Tell us why and how you got into filmmaking.

Barosa: I have wanted to work with films since I got a toy camera that recorded directly to VHS players (through an incredibly long cable) when I was 10. I grew up, studied marketing, dropped out, went to Argentina to study film, and 17 years later, I’m here. It hasn’t been easy, but I never thought of giving up, because I love making films too much.

Casavecchia: In 1999, at 19, I used all my savings to leave Buenos Aires for a backpacking trip in Europe with two childhood friends. Just weeks before returning, Argentina’s economy collapsed. There was, suddenly, no country to return to. We chose to stay and make our lives in Barcelona, but soon our visas expired, and we became “illegal immigrants.” Regular jobs were off-limits due to our immigration status, but we found that making music videos and commissions was less scrutinized by the government. Each of us had some knowledge of filmmaking; we taught each other animation, filming, and editing. Filmmaking became my survival mechanism.

Catapreta: My audiovisual background is essentially the result of the TV culture in the 1980s. I was born in 1976 and experienced the significant role and impact of Brazilian TV content on people’s lives, shaping culture, political thinking, language, and the way entertainment is consumed. I wanted to pursue filmmaking (audiovisual) because I was captivated and wanted to tell stories that would be seen on TV.

Susi: I come from the theater. I’m a classically trained actor and currently the associate artistic director of IAMA Theatre Company in Los Angeles.

In 2020, during the COVID-19 lockdowns, IAMA was forced to pivot to a virtual season. This led me to develop, workshop, and direct a one-woman show called Anyone But Me starring Sheila Carrasco for the screen. Once I got a taste for film, I couldn’t stop. When the camera broke through the proscenium, I had more control over the story I wanted to tell. In theater, after you give a note, you have to sit back, say a prayer, and hope the actor takes it. With film, I’m able to craft the performances. I love puzzles, and film is just that — one delicious puzzle that’s begging to be solved.

Why is filmmaking important to you? Why is it important to the world?

Casavecchia: I was raised on films. My dad is cinephile and had me watch the big European directors of the ’50s and ’60s at home, while I would watch all the American pop films in the cinema with my friends. In many ways, I’m still trying to reconcile these two major schools of cinema.

Marcelo Piñeyro, the famous Argentine filmmaker, once told me cinema is like a giant ball of clay, several feet high. We can aspire to put our fingerprint on it, but it changes only over time, generation after generation. Individual films might not aspire to change the world, but cinema as a whole has the power to influence world events.

What is something that all filmmakers should keep in mind in order to become better cinematic storytellers?

Casavecchia: Your quirks are your signature move. You need to fine-tune your intuition to distinguish the good quirks from the bad. But sometimes, repeated mistakes plus time equal artistic style. Odd choices are at the heart of good artistic expression. Don’t just replicate what feels right; defend your weirdness. Nobody may understand it in theory, but they’ll get it in execution. So, go out and actually make things happen.

Catapreta: Honesty!

What three things do you always have in your refrigerator?

Barosa: Ice cream, beer, and cheese — the order and quantity vary depending on the mood.

Susi: Cholula, Tapatio, and Sriracha.

One thing people don’t know about me is _____.

Barosa: I hate drinking anything hot. Coffee, tea, hot chocolate, you name it. I like it ice cold.

Susi: I once drove a press van in President Obama’s motorcade.

Early bird or night owl?

Barosa: Night owl. Filled this form out at 2 a.m.

Casavecchia: My brain calls it quits after 6 p.m. Nothing constructive comes out of me at night.

Tell us about your history with Sundance Institute. When was the first time you engaged with us? Why did you want your film to premiere with us?

Barosa: As any self-respecting film buff, I’ve known of the Festival since I got into movies in my teens. When I eventually started making movies myself, I submitted everything I shot to the Festival. Guess the 17th time is the charm.

Boi de Conchas is the film I’m the most proud of. To premiere it at a Festival I have always admired is a dream come true. I wish I could text myself in the past, 17 years ago, to give a pat on my back and keep up the good work.

Casavecchia: My history with Sundance dates back over a decade, to when I was writing my first feature, Finding Sofia, and dreaming of showing it at the Festival. That dream didn’t come true, but three years later, BattleScar, which I consider my second film, was accepted into the New Frontier program. Since that experience, I’ve felt nothing but gratitude toward everyone at the Institute. The Festival introduced me to the only film community I’ve ever had, and many people who worked on Border Hopper I met at the Festival over the years. For all of us in the project, it was clear that this was the best home for the film and a dream launchpad for the kind of ideas it discusses.

Who was the first person you told when you learned you got into the Sundance Film Festival?

Barosa: I read the selection email at night while my wife was with my daughter, making her sleep. I invaded the room and told them both the news. My 2-year-old had no idea what I was talking about but was super cheerful because she knew my wife and I were overly excited. Thinking back on it, it wasn’t a good idea, since it took a couple of hours to make my daughter fall asleep after that.

Casavecchia: My wife and co-writer Mercedes Arturo <3

Catapreta: I told my production partner, Daniel Nunes, who has been in charge of all the sound aspects of my films since 2010.

Susi: My boyfriend was next to me when I got the news. There was a lot of screaming and crying and laughing. I immediately Facetimed Angela and [producer Grayson Propst]. When I told them, their faces were priceless and I have the screenshots to prove it. It was a really special morning.

What’s your favorite film that has come from the Sundance Institute or Festival?

Casavecchia: I’m an obsessive archivist! I had to check my lists because there are so many films that impacted me over the years that came out of Sundance. While working on my first film, Mike Cahill’s Another Earth struck me as the perfect film — a vast premise in a tight, intimate package. It’s still one of my favorite films by a contemporary director.

Catapreta: Precious!!!

Susi: Oh there’s too many to count. CODA and Whiplash are two films that left me both speechless and inspired.