By Vanessa Zimmer

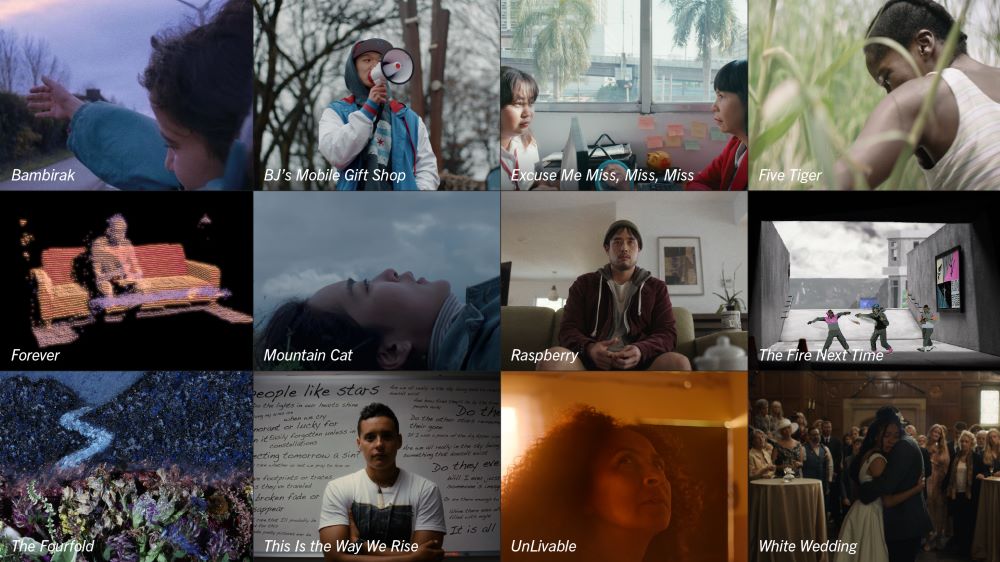

Welcome to part two of our four-part series introducing the short films and directors from the 2022 Sundance Film Festival Shorts Program.

All Members of the Sundance Institute get their own private screenings, from the comfort of their own homes, of these 12 short films from past Festivals. If you’re not a member and join by our extended deadline of July 18, you can also receive access to this curated selection.

Just recently, we covered the 2021 Short Film Jury Award winner Bambirak, as well as the charming BJ’s Mobile Gift Shop and the alarming Excuse Me, Miss, Miss Miss. (Click here if you missed it or want to review.)

The Sundance Film Festival Shorts Program, presented by XRM Media, allows Members online access to watch the collection, which also includes UnLivable, Forever, Raspberry, Mountain Cat, This Is the Way We Rise, and White Wedding. And that’s not the only benefit of joining. Membership also offers invitations to in-person private screenings, early access to Sundance Film Festival tickets, and more ways to stay connected with other Sundance-supported artists throughout the year.

So, it’s time to get excited about one of those year-round benefits — this summer shorts collection. In this installment, we introduce three very different animated films and their directors.

The Fire Next Time, directed by Renaldho Pelle

In his short film The Fire Next Time, director Renaldho Pelle seizes upon rough, colorful animation, the sounds of city streets, heavy percussion — and the absence of dialogue — to convey the culmination of economic blows and social oppression that eventually boil over in violence.

Pelle based the film on the 2011 London riots, but he wanted the themes to be universal. He intended the story to be relatable, for instance, to “people feeling trapped in their surroundings, and how social issues manifest as unrest if left unaddressed.”

“These are things that are common problems the world over,” he adds. “We felt that having the film be silent would allow people from all over the world to relate more to the feelings of the characters.”

Ditto the animation: “For millennia, drawing has been humankind’s way to record and communicate. It is deeply entrenched in us to understand that language,” says Pelle. “Film is the new medium in that respect, and so I trust animation to communicate emotion even when dealing with difficult subject matter.”

The animation process was long and complicated, involving painting characters on glass, stop-motion backgrounds, projection to create shadows, plus much, much more. Pelle says he was lucky to have a group of dedicated people and the backing of the National Film & Television School.

“When I was finding it difficult, and doubting what we were doing, there was always a supportive and encouraging voice to keep me on track,” he says. “I can’t begin to say how thankful I am for that.

“The other ingredient that is key is to make stories about things that are important to you. It really helps you to fight through the hardship if you believe in the value of what you are trying to say.”

Five Tiger, written and directed by Nomawonga Khumalo

Deeply religious Fiona struggles to support a sick husband and young daughter in her South African community. She resorts to a relationship that involves sex for money to help pay the bills.

Director Nomawonga Khumalo says the story was inspired by an encounter with a prostitute who also sold firewood to bring in income. “She didn’t fit the stereotype popularized by the media of a cheeky, high-heel stomping ‘lady of the night,’ ” Khumalo explains. “Her tattered clothing made her broad daylight endeavors hard to believe…. Our interaction informed me of her quest to make a better life for her daughter who wasn’t privy to how hard she had to work to make her money and spent it on nonsense, a naivety she both worries about and envies. She was a devout Christian who believed her poverty was not in vain.”

Khumalo, a South African director and writer, has since expanded the story to develop a full-length feature, The Bursary, “which also interrogates the cultural, religious, and feminist spaces in the South African context.” “How The Bursary’s narrative adds to the conversation is by showing an appreciation of tradition while holding it up to the light against modernity and interrogating how the two co-exist,” she says.

Five Tiger is Khumalo’s first short film. But she never questioned tackling such weighty subject matter: “The stories have a way of presenting themselves to you and nudging you until you get them out. All I am is a conduit and so was not as active in the choice of subject matter as I’d like to believe. In many instances, the stories choose us.”

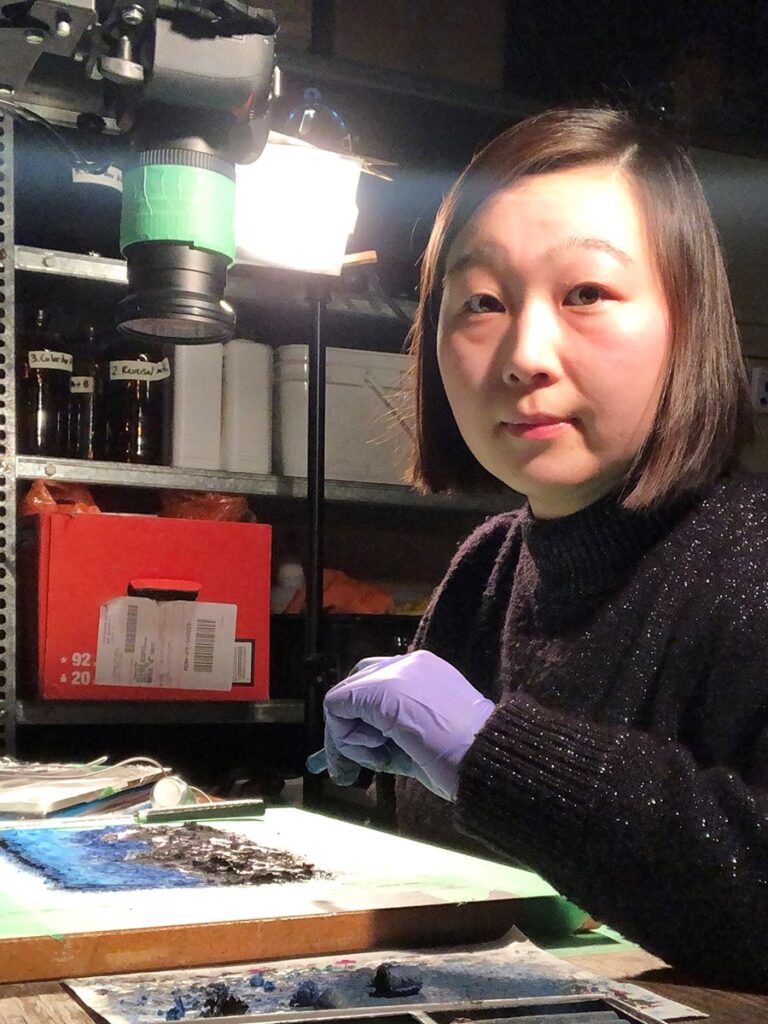

The Fourfold, written, directed, and animated by Alisi Telengut

A world of the Earth Mother, the ski deity Tengri, the Fire God, and other shamanistic traditions of Mongolia come alive in The Fourfold — a short animated film by Alisi Telengut. This is a worldview Telengut learned about through her grandparents, who lived a nomadic life on the Mongolian grasslands. So it seems only natural that her grandmother should be the voice that tells the story.

Accompanied by ancient songs and flowing, pulsing, vivid Van Gogh-ish colors, Qirima Telengut sounds just like a wise grandmother, plainly telling of Indigenous beliefs that attribute conscious life to all things, including the rivers, the trees, the flowers, and all inanimate objects.

Alisi Telengut, the granddaughter and filmmaker, witnessed a few of the rituals as a child — the Ovoo, in particular, a shamanic stone altar heaped with rocks and marked by bright blue, yellow, and white ceremonial scarves. There, the people circle the altar and honor Tengri, Mother Earth, and all of nature.

“The rituals and beliefs that I learned are performative acts that connect humans with the nonhuman in a more-than-human world, showing respect and honoring nature, in contrast to the anthropocentric and exploitative perspective that still dominates in our time,” Alisi Telengut explains.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that I should go back in time and live as my ancestors used to, but it is to learn from their wisdom and stories, and carry them to our present troubled world and to even project them into a collective future.”

Telengut believes that conveying the story through animation enhances it. “It brings an imaginary and speculative sense to the film,” she says, “with reconstructed, revisioned or imagined scenes that might carry more emotional connection to the story.”

Each piece of artwork for the animation is held in place, and a fixed camera from above records the images frame by frame. “It’s a process of time-lapse photography of painting/animating,” Telengut says. “The handmade aspect reminds me of embroidery, weaving, or knitting, which stitch stories, design patterns, and interconnectedness into the materiality of the artwork.”

Next week: Stay tuned for part three of our series on the 2022 Sundance Film Festival Shorts Program.

Everyone Is Cordially Invited to Celebrate Queer Joy in “The Wedding Banquet”

“The Ugly Stepsister”: A Cinderella Body Horror Story That Will Leave a Crowd in Shambles