By Stephanie Ornelas

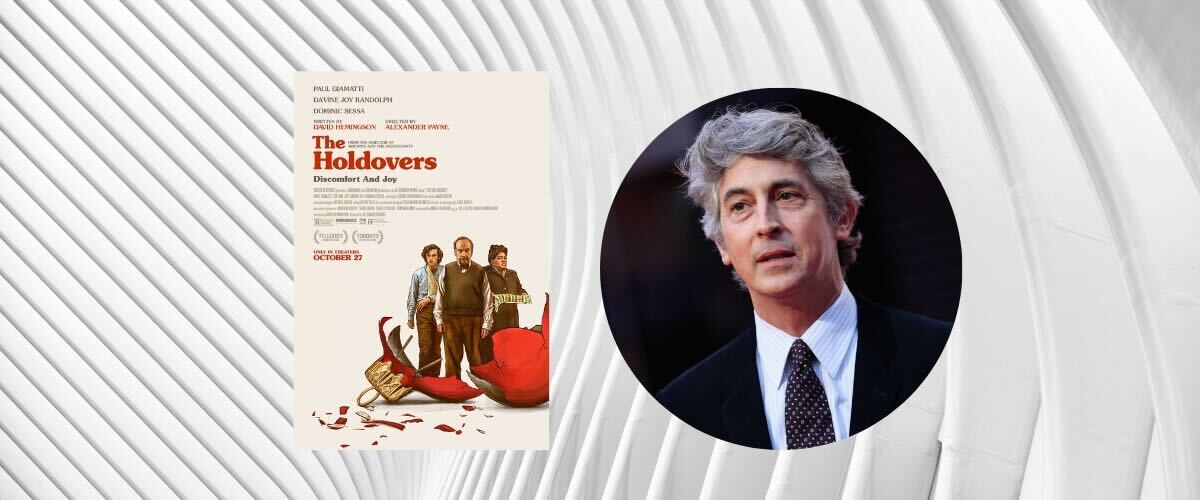

Alexander Payne has deep roots with Sundance Institute, having been a lab fellow, creative advisor, and a Festival juror over the last two decades. When he joined Sundance Collab for an Advisor Studio in November to talk about his hilarious and heartwarming Oscar-nominated film The Holdovers, the group was eager to hear about his process and filmmaking experience.

In the film, Paul Giamatti plays a grouchy New England prep school teacher who must remain on campus during Christmas break to look after a small group of students with nowhere to go. He soon forms an unexpected bond with a promising but troubled student (Dominic Sessa) and the school cook (Da’Vine Joy Randolph).

Payne knew he wanted to make a movie about boarding school students stuck with a reviled teacher over a holiday break when he first saw the 1935 film Merlusse. “I saw that French film about 12 years ago, and I thought the setup could make the premise for another movie, one that I’d be interested in making and seeing,” Payne says.

At the end of the virtual discussion, listeners had questions about everything from special effects to what surprised Payne most during production and whether he felt film school was beneficial to his career. Discover some of our favorite quotes from the Advisor Studio below, including Payne’s approach to releasing creative control and working with Giamatti once again — nearly 20 years after they teamed up for Sideways.

Advice for working harmoniously with writers:

“It’s like a relationship. Your relationship with your close collaborators in film, specifically [your] editor, cinematographer, co-writer — a lot of that is casting and just who you like, who you get along with, who will share your work ethic, and if you basically have a similar sense of drama and of comedy and drama.”

On giving actors creative freedom:

“A really beautiful thing [about] filmmaking is how many different artists you get to meet who each contribute his or her part to the film — his or her artistry. I’m there to direct the creativity of others, not necessarily come up with it all myself. I entrusted Paul with creating this character, this human being. And then I’m there to say, ‘Okay, here’s your mark. This is how we’re going to block the scene.’ Or if I need to say, ‘What you’re trying there is a little bit too much or too little.’ If the acting is good, the director then has four directions: louder, softer, faster, slower. You’re just tending to the dynamics of the performance. That’s what I’m able to do with good actors and was able to do specifically in this [film] with the three leads.”

On building chemistry between actors:

“Actors, when they’re supposed to have chemistry in a movie, part of their job is to create that chemistry — to spend time together, not necessarily with me, but to spend time together off screen, so that on screen, there’s a fluidity. I had that 19 years ago with Paul Giamatti when we made Sideways. He had never met [co-star] Thomas Haden Church. I usually have actors out about a week before we start shooting, but in this case [for The Holdovers], I told the bean counters I needed the money [to have the actors] come out two weeks in advance. Yes, to do some read-throughs with me, but more so that they could have time together — to go to the movies together, play golf together, have dinners together, and they did that. Part of it is the effort that the actors know they have to put into creating those relationships. And don’t forget that cinema simply has a wonderful capacity to lie. You just show something and suggest that that’s what’s happening, and that’s what’s happening.”

On collaborating with David Hemingson:

“I thought, ‘Here’s a writer who knows that world much better than I.’ He grew up in it. And maybe he would be the right person to get this script on its feet. I always get involved in rewriting and guiding it, but I thought he could get it up and running, and he accepted the challenge. We worked out the story together. He’d propose three, four, five different possible storylines. He’d show me drafts, portions of drafts, scenes, and run things by me. The end result is that we had a script that was directable by me and personal to both of us. [It was a] real rich experience. It was my first experience in, let’s say, directing a writer.”

On the impact of film school:

“Nowadays, if you have the discipline — big ‘if’ — you can teach yourself filmmaking with YouTube tutorials. The amount of material about how to make a film and how great films have been made is extraordinary. Similarly, the means of production is far more accessible financially than it ever was before in film history. To have access to a camera, to have access to sync sound, to have affordable lights, to then be able to edit at home on your computer, including sound design — these are extraordinary things available to the home director. But will you do it? Will you have the discipline to write a script and find actors? It’s like going to college. Could you buy all those books yourself and force yourself to write papers?

“[It] was the 1980s when I was in film school. That pre-dates the accessibility of equipment that I just referred to. I needed to go to a conservatory. What you have are comrades who, like you, are eating, drinking, sleeping, breathing film all the time. [Film school] was super valuable for me. I can’t recommend it for everyone. But I had an extraordinary experience.”

Check out the full discussion and Q&A for more from Payne, including his decision to bring on first-time actor Dominic Sessa, a high school student at one of the schools Payne was scouting. Finding Sessa “was a genuine discovery,” marvels Payne.

For more tips from filmmakers, check out the on-demand course Preparing to Direct Your First Feature Film with Andrew Ahn. And for updates on upcoming Collab events, courses, and discussions, sign up for Sundance Collab’s newsletter here.