photo courtesy of American Promise

by Aramide Tinubu

Education has always been seen as a golden ticket in this country. In 2015, the Schott Foundation for Public Education released a disheartening report stating that only 59% of Black males graduated from high school in the United States. While Black girls — who share many of the same risks as their male counterparts — have fared better on average in the U.S. education system, anti-Black racism in our schools is failing Black boys.

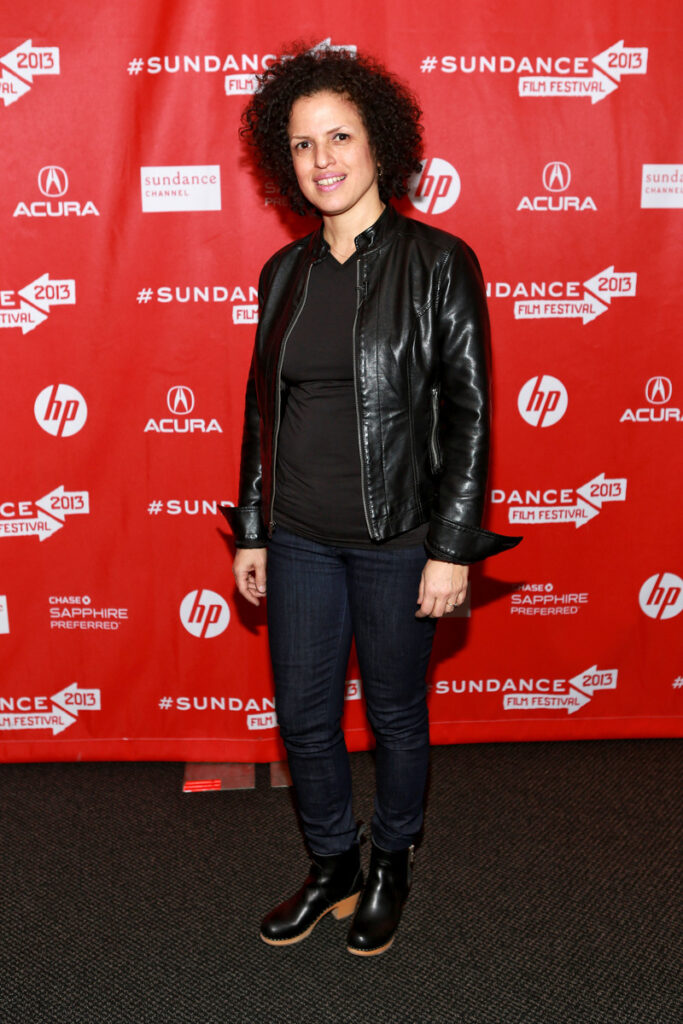

Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson, a Harvard-and Stanford–trained psychiatrist and a Columbia Law School graduate and filmmaker, respectively, knew the statistics. As their son, Idris Brewster prepared to enter kindergarten; the couple knew they needed to take charge of his education. The Dalton School — a private, predominantly white school located on Manhattan’s Upper East Side — seemed to offer avenues for the brightest future for Idris. After being criticized for its lack of diversity, the school was actively seeking Black and brown students.

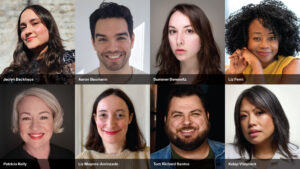

In 1999, Idris and his best friend, Oluwaseun (Seun) Summers, entered kindergarten at Dalton. Over the next 13 years, Brewster and Stephenson documented Idris and Seun’s educational and family experiences in their compelling and intimate documentary, American Promise.

In the film, the boys grapple with feeling othered, the pressures of academic performance, familial changes, puberty, and everything in between. American Promise debuted at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, spotlighting the fractures in our education system. It won the U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award.

Now a decade after the film premiered and nearly three decades since they first began filming, Stephenson and Brewster are looking back on how the landscape of education has shifted, how American Promise radicalized their filmmaking, and where Idris and Seun are today.

“There are lots of things we’d change,” Brewster explains over Zoom , when reflecting on making American Promise. “And we radicalized as filmmakers over the last 10 years. Thanks to the impact of the film, the questions that were raised, and the trajectory of our kids — meaning our two sons and Seun.”

While the couple’s perspectives as parents and filmmakers have changed over time, American Promise unfurled a conversation that desperately needed to be had. “I’m very proud of the piece, its message and storytelling also, its boldness and the risks that we took in how we told the story and how we decided to tell it on our own terms,” Stephenson says.

While the film focuses on Dalton School specifically as it was in the early 2000s into the early 2010s, Brewster reiterates that American Promise is not about a singular institution or even about the particular experiences of Idris and Seun. “We sometimes worry that there tends to be a focus on private institutions, as opposed to a clearer understanding that systemic racism is ubiquitous,” he says. “And you can point at any school and find what happened to our sons, be it private, public, or parochial. We learned that to some extent when we toured the film.”

The education gap and the school-to-prison pipeline built to entrap people of color — specifically Black males, are not new topics. However, American Promise offered a new language to discuss it, specifically regarding the Black middle class.

American Promise resonated with a new generation of parents and their Black children. Yet, Stephenson recalls some moments of apprehension while making the film, mainly since the film showcased some of the most personal moments of her family life. “We never stopped questioning it,” she recalls. “It was just the constant level of questioning: questioning our role, questioning the balance between parenting and filmmaking, questioning the level of vulnerability that was being exposed with regards to Idris and Seun, questioning our relationship with the Summers family and them questioning us. The self-doubt never really left. It was ever-present. It was also very much present in the editing process.”

Despite the success of the film at the Sundance Film Festival and afterward, some of Stephenson’s fears did come to fruition. She and Brewster received some pushback from their peers. “Questioning in terms of ‘Why would you subject these Black kids to this level of scrutiny?’” Brewster remembers. “‘Are you overthinking and exaggerating the impact of this?’ We had to make some decisions. We discovered that, as moderate as we think this film was, it was threatening to many people. We were told that it made no sense to certain communities.”

However, many people did resonate with American Promise. The film became a topic of conversation amongst educators, parents, families, and students, especially across the Black diaspora. “It’s very much about point of view, the way this film is appreciated and seen,” Stephenson says. “At the time, the idea of racism toward Black middle-class life wasn’t developed in the same way because we were fighting the onslaught of affirmative action that was being dismantled. There was this idea of a colorblind society. [President Barack] Obama was just elected. The film became part of that dialogue of the demystification of Black exceptionalism. So, the risk we took around vulnerability had a tenfold return because of how people were able to connect to that.”

Though diversity and inclusion are buzzwords still regularly used today, American Promise highlighted the illusion around the terms. “Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) doesn’t change the system,” Stephenson explains. “It’s sort of like, the system has these pressures, and then there are these valves that need to be open for the system to sustain itself. So, DEI is a way of opening it, so we don’t get riots, so we don’t get uprisings.”

Brewster adds that for diversity and inclusion to work, it must be expansive. “What do diversity and inclusion mean if you don’t diversify perspective?” he asks.

American Promise probably couldn’t be made in the same way today. Our society and the cinematic world are in very different places. “If it were to be done today, it would’ve been a series,” Stephenson says. “Because back in the day, we had to fight to get two hours when it could have been a three-part film or a limited series, very easily. There are so many themes that we left on the cutting room floor. And people didn’t want to hear anything about a series back in the day. That was not discussed. So, in that sense, it would’ve had a different life.”

For the subjects of American Promise, the film was just a tiny window into their lives. A decade after leaving high school and the film’s launch, Idris and Seun are thriving. “[Idris] has a collective in Brooklyn — Movers & Shakers,” Brewster says. “He’s got 10 employees. They create monuments to POC figures nationwide. He has a systemic understanding of how the system works, what makes sense for social justice, and what that looks like for his generation. We don’t speak to Stacey and Tony [Summers] much. But [Seun] is here all the time.” Seun has also been thriving. He still lives in Brooklyn and works as an editor for CBS. In his free time, he produces music beats and often works with Idris.

Reflecting on American Promise, one thing is paramount for the filmmakers. The American education system in both the private and public sectors should never be the foundation for learning, especially when it comes to Black people — and, in this case, Black males. “Growing up in a racist world means that you’re going to be racist against yourself,” Brewster explains. “And anti-Blackness breeds anti-Blackness. If the school is not working on anti-Blackness, the parents need to.”