Nate von Zumwalt, Editorial Manager

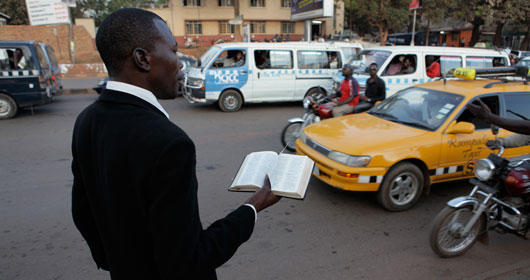

In making his alarming, often outraging documentary God Loves Uganda, director Roger Ross Williams embedded himself in the eye of a cultural thunderstorm—one marked by stanch moral and religious adherence and a shocking code of ethics surrounding homosexuality.

God Loves Uganda plays like nothing less than an investigative thriller, penetrating a potent American evangelical movement taking place in a vulnerable East African country. Perhaps the only thing more rousing than the mission itself, is the man crusading it. Williams is, in America, an openly gay filmmaker. In Uganda, where a bill is up for vote to make homosexuality punishable by death, he is considered a “monster.” Below, the Oscar-winning director shares the details behind the treacherous making of his 2013 Sundance Film Festival Audience Award winner, which opens in theaters this Friday. Here are 5 Things You Should Know About God Loves Uganda:

1. Despite their vast moral differences, Williams and his religious subjects maintained amicable relations.

“There’s a group of religious leaders who are the driving force behind the bill. It was rough going at first. But as we got to know each other, we actually grew to like each other and enjoy each other’s company, even though philosophically their idea is that I don’t have a right to exist as a gay man.”

2. Williams, who hadn’t explicitly revealed his sexuality to the Ugandans, was exposed as a gay man during the production of God Loves Uganda.

“We didn’t talk about me being gay, but there was one hairy moment when the Ugandans found out. I was outed, so to speak, in Uganda when I was invited to dinner at the home of an antigay pastor. I was terrified. Someone who wanted to expose me sent them an email that said I’m gay. They’d pulled an interview I’d done from the Internet. The Ugandans said, “We love you and we want to pray for you and cure you.”

3. While many of the Evangelical leaders in Uganda do not commit violence, they also don’t preclude it.

“The film is about something much bigger than me and my personal experiences. It’s about the bigger Evangelical movement. It’s OK to believe that homosexuality is not God’s way, but it’s not OK to condone or support or even look the other way when there’s violence against LGBT people. Many of the Evangelicals who are missionaries in Uganda, even though they’re not directly participating in violence, will look the other way and pretend it’s not happening.”

4. Building trust in his subjects was a protracted process for the director.

“It happened over time. When you go into a project like this you’re the mainstream media and there’s a lack of trust. Over time you get to know each other and have meals together and those walls start to fall down and people begin to speak openly. It takes time— a year or two years—to develop those relationships.”

5. With his film, Williams hopes that American Evangelicals will reconsider their approach to spreading the gospel in different cultures.

“I want American Evangelicals to understand the language they use may not translate the way they think it will to a different culture. I hope we can screen the film in churches across America and people will say that’s not what we want. I want Christian audiences to hold their church and pastor accountable and when they put money in the collection plate that’s going to help an orphan in Africa, that it’s really going to help an orphan in Africa, not fuel hatred.”