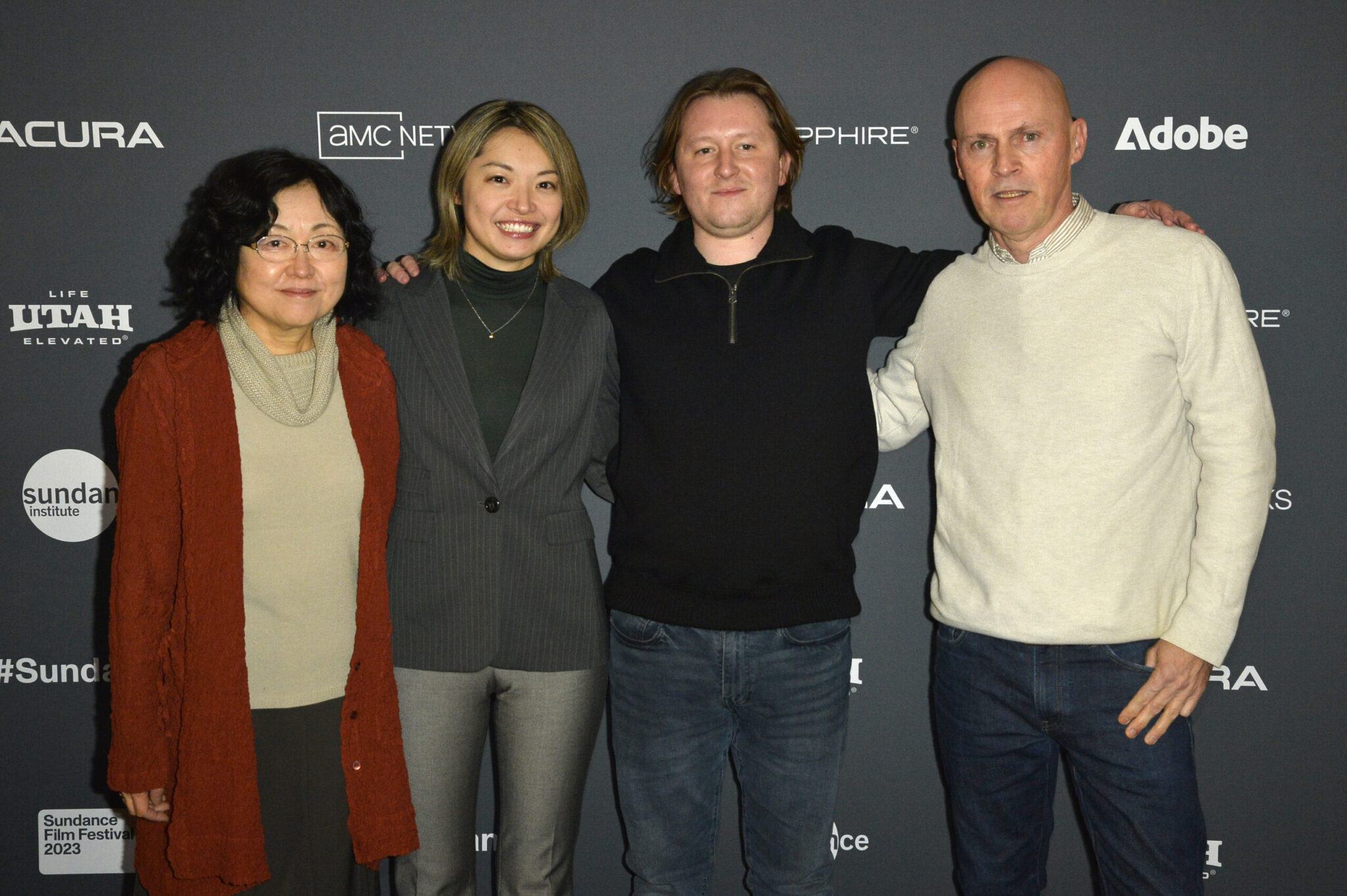

PARK CITY, UTAH – JANUARY 20: (L–R) Shoko Egawa, Chiaki Yanagimoto, Ben Braun, and Andrew Marshall attend the 2023 Sundance Film Festival “AUM: The Cult at the End of the World” premiere at the Library Center Theatre on January 20, 2023 in Park City, Utah. (Photo by Jerod Harris/Getty Images)

By Lucy Spicer

During the morning rush hour on March 20, 1995, chaos broke out in the Tokyo subway system. Sarin, an extremely toxic nerve gas, had been released in multiple subway cars. Thousands were injured, and 14 in total died as a result of the attack. This harrowing event was the culmination of a decade of sinister activities at the hands of Aum Shinrikyo, a doomsday cult helmed by Shoko Asahara.

Ben Braun and Chiaki Yanagimoto’s directorial debut, AUM: The Cult at the End of the World, is an unflinching portrait of Aum Shinrikyo based on the book The Cult at the End of the World: The Terrifying Story of the Aum Doomsday Cult, from the Subways of Tokyo to the Nuclear Arsenals of Russia by David E. Kaplan and Andrew Marshall. Through an abundance of damning archival footage and interviews with individuals affected by the cult (including one former disciple of Shoko Asahara), the documentary chronicles Aum’s transformation from a seemingly innocuous yoga school to a terrorist organization.

In the film’s post-premiere Q&A at the Library Center Theatre on Friday, January 20, Yanagimoto, who grew up in the same prefecture in Japan where Aum had its laboratory headquarters, explains what drew her to this story. “When the subway attack happened, the whole nation was in shock,” she recalls. “I was in middle school. I remember my mom and all the parents telling their kids, ‘Be careful of these people roaming in the mountains in white robes.’ It was really vivid in my memory, and yet I didn’t really know why it happened, or who were these people.” These questions led Yanagimoto and Braun to create a story-driven documentary.

Though most of Aum’s story is told through people who tried to dismantle the cult from the outside, the film lends crucial historical context to the nefarious group’s creation, detailing how it was able to operate so successfully (and visibly) in Japan at the time by adopting an eccentric image and establishing contacts in the media, the police force, the military, and beyond. Shoko Asahara appeared harmless in silly TV appearances, and cult recruitment materials in the form of books and cartoons circulated freely.

AUM divulges what it can about the inner workings of the cult, but some things remain shrouded in mystery. “Aum itself, as it’s portrayed in the film, is kind of meant to be opaque,” explains Braun at the post-premiere Q&A. “It’s sort of like a faceless monster to a certain extent.”

Testimonies from journalists and lawyers provide valuable, insightful analysis nevertheless, while accounts from relatives of cult members reveal how deeply damaging the consequences of Aum’s acts were and how they continue to reverberate in Japan today.

In its final scenes, the documentary’s relevance is driven home by Andrew Marshall, who prompts audiences to examine how there is ample opportunity for another group like Aum to establish itself today: “When you look at how polarized politics is in the U.S. and the UK, there’s a cult-like element of that where you have both sides that have their own sort of alternate reality, if you like, where they have their own facts and they’re really, you know, immune to outside influence or what the other side would call the facts. So it is a worrying time and you can see elements of Aum in our modern lives.”