By Shahnaz Mahmud

The power of dance lies in its ability to touch our emotions solely through the body’s expression. Wordless verse, poetry in motion, call it what you will, the art form viscerally moves us. Our senses heightening in the same way when the lights dim in a darkened cinema and the movie before us unfolds.

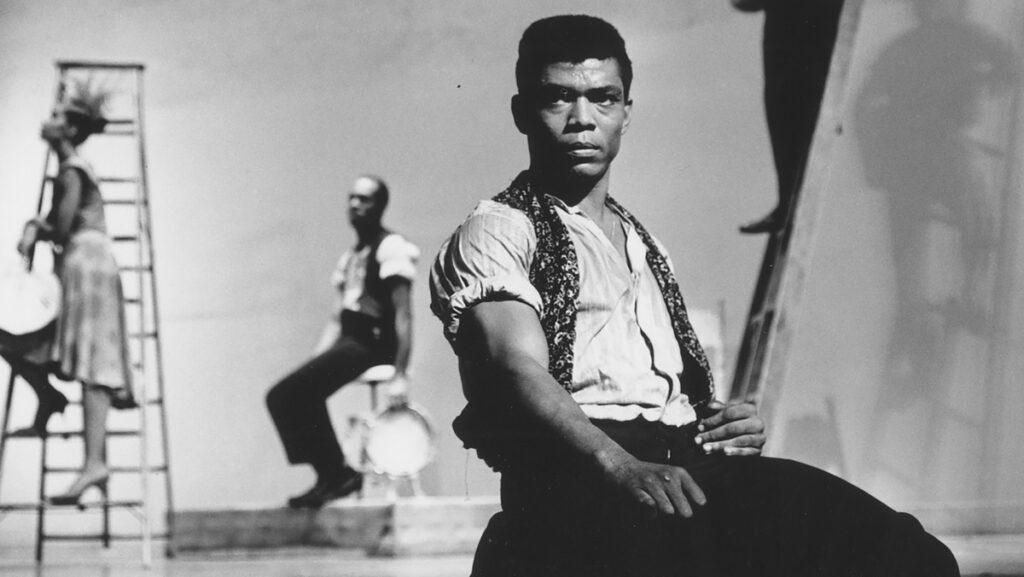

In Jamila Wignot’s documentary Ailey, which debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in 2021, the director not only aspires to give insight into the life of the celebrated — yet deeply private — choreographer Alvin Ailey, she desires to recreate the experience of watching Ailey’s choreography live on stage.

“In my body of work, I have tried to explore more ways that storytelling can be told visually,” says Wignot over the phone. “So with dance, and particularly with Mr. Ailey’s works, which are very narrative, it felt like there was going to be a way to let go of speaking to what the dance is doing, and create moments in which the dance could do its own work to speak for itself.

Ailey’s pre-eminence in 20th century choreography leaves a lasting legacy today — his name is still synonymous with innovation in modern dance. Ailey was an African American born into poverty in rural Texas in 1931 and, as the film shows us, recognized that the art form was his destiny when he was exposed to it as a young teen. He created the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater in 1958, in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, and offered emotionally rich dance pieces that spoke to the African American experience.

Wignot was introduced to the project through Stephen Ives and Amanda Pollak, both principals of Insignia Films. She was attracted by Ailey’s stature in modern dance and the fact that nothing substantive of him as an artist existed in documentary form. But, she also happened to be an ardent fan of the Ailey dance company. Wignot discovered it as a college student — in fact, this was the first company that led her to consider the creative importance of dance.

Living up to the art form

Wignot says her initial excitement was over the opportunity to make a film that would have dance in it. But, then came a greater desire: “If you’re going to do a documentary about an art form like dance, then you have to live up to that art form.”

The actual dance aspects featured within Ailey are many and varied — just as Wignot likes it.

The filmmaker weaves in original performances from some of Ailey’s most acclaimed works. Among them is Revelations, which debuted in 1960, and is perhaps Ailey’s most beloved work. Ailey’s use of African-American spirituals, song-sermons, gospel songs, and holy blues within the piece speaks both to the grief and joys in life.

Wignot also brings contemporary dance into the mix, filming dance rehearsals of the current Alvin Ailey company. The choreography still speaks to Ailey’s bold choices, sometimes requiring the audience to reflect on race relations.

The movement throughout the film is all ultimately grounded in Wignot’s own artistic choices. She looks to Ailey’s mastery of craft, which was very much based in the search for truth.

“I always felt that dance was a natural part of what I wanted to express — what I can do with my body is a very important part of me,” he says within the film. “It creates movement. I am searching for truth in movement.”

An exercise in memory

These utterances are critical to Wignot’s own creativity. Ailey died at age 57 from AIDS in 1989. During her research, one of the film’s happy miracles was uncovering never-before-heard recordings of Ailey that were made while he was working with author A. Peter Bailey on his autobiography, Revelations: The Autobiography of Alvin Ailey. The book was unfinished at the time of his death, but was later completed and first published in 1995. The audio depicts Ailey’s frankness and honesty as he opens up about his youth, career, and private life. Wignot notes the quality of meditation to it, which became the underpinning of her film.

“To read it on the page and see Ailey’s poetic language as a kind of written text is one thing, but to hear him speak and to really feel the wild difference between the way he speaks when he has a press engagement, or is trying to raise money for the company, all of the ways that he speaks his public persona, versus in this real kind of meditation, it’s a real exercise in memory,” she says. “The minute we had it, we realized we had huge swaths of his story.”

Ailey references his “blood memories”: memories that speak of his family and life growing up in the poor South. Wignot’s poetic use of imagery, often through grainy celluloid, captures the feeling of the moment.

There’s a point in the film that begins to follow Ailey’s life as it starts to spiral downwards. Ailey stands on a subway platform quietly waiting. Soon his mental state begins to unravel. Bodies in motion are moving in reverse now, and there are harried shots of New York City adding to the freneticism Ailey was experiencing inwardly.

Wignot reflects on this artistic choice: “We just ran it backwards just to see — it really came about as a kind of experiment…and the way that shot works forward is that you kind of come around the corner and you push into Alvin. And I was saying to my editor, ‘I want us to be moving away from him. The world is moving away from him, he is further isolated. And so the goal of this is to feel like everything is not just moving backwards and is out of sorts, but it’s also moving away from him.”

The filmmaker adds that this particular rendering is one example of the film being experiential. As Ailey’s bipolar state is forcing a breakdown, Wignot sought to depict that in a meaningful way.

“I am always wanting in my own practice to try to lean more increasingly into the way that visual material can speak to the emotional moment, or the subtext, or the story,” she says.

Becoming emotionally available with the work

Ultimately, Wignot had a specific goal with the film: to go on a journey with Ailey and reconnect his works to his artistic practice, his ideas, and the ways in which he was making sense of his own life.

“Outwardly, Ailey was charismatic and magnetic — an ever inspiring figure,” she says. “And then behind closed doors, when he is alone, he is very much alone. Often because he hadn’t really fostered intimate relationships — platonic, romantic.”

There was this sense of how much he was struggling with internally as an icon, an artist, and being a gay man who hadn’t shared that with the world. Wignot says it was hard to see how much Ailey didn’t seem to have. “It made me question myself,” she says.

During the filmmaking process, Wignot found herself immersing in her work in a much different way thanks to the choreographer.

“Ailey, his life and his vision, and his own struggles required me to be emotionally available, which not all of my work has been,” she says. “I had to be extremely vulnerable in my process in ways that made me really uncomfortable — you know, to be open to saying I didn’t know what I was doing in certain moments, or to seek out help, which is really hard. And those kinds of things felt connected to Mr. Ailey’s own struggles.”