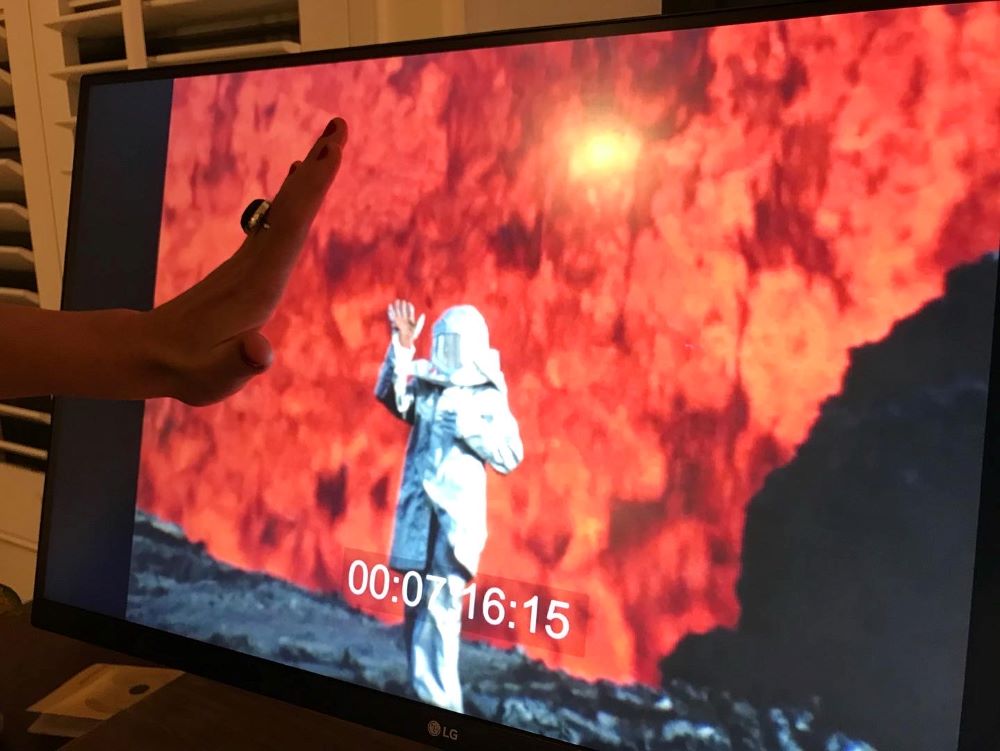

Sara Dosa and her film team visited active volcanoes as part of their research for “Fire of Love.” (Photo courtesy Sara Dosa)

By Vanessa Zimmer

Talk to Sara Dosa about filmmaking for an hour or so, and, even before she says it outright, you get the feeling she’s discussing something spiritual.

The director of the Oscar-nominated documentary Fire of Love came to the film world from a household steeped in anthropology. It was the stuff of everyday dinnertime conversation — the dynamics of meaning and power among humans, the relationships among people.

“My mother, she’s now retired, but she was a professor of anthropology, and I love her very much and always wanted to be like her,” Dosa explains with a laugh. In fact, Dosa earned her master’s in anthropology and was on her way to a doctorate when she got distracted by the collaborative storytelling aspect of film.

“I think I’m endlessly curious about how people make meaning with, and out of, relationships with each other and with nonhuman nature,” Dosa begins. “And, for me personally, the stories that are resultant from the process of meaning-making help me feel deeply connected to what it means to be human.” She pauses and laughs.

“That may sound too heavy or dramatic, but it’s really true,” she says, laughing again. “It’s like making films, it’s almost akin to a kind of religion for me. It’s how I feel connected to others and to ideas.”

Her transition to filmmaking from an anticipated career in academia was fairly seamless: Dosa’s first directorial effort, The Last Season, was inspired by an anthropologist who delivered a lecture at Dosa’s school on mushroom-picking communities and ultimately introduced Dosa to members of that group.

The documentary focuses on Roger, a Vietnam veteran, and Kouy, a Cambodian refugee who fought the notorious Khmer Rouge. The two bond in Mushroom Camp — a tent community that pops up each fall in the woods of Oregon — and develop a relationship that begins to heal their emotional wounds of war. Their friendship is threatened when Roger becomes ill.

Jump forward to Dosa’s latest film, Fire of Love, a simultaneously heartwarming and heartbreaking documentary about Maurice and Katia Krafft, two playful French scientists in love with each other and with chasing erupting volcanoes. Their footage, images, and writings contributed volumes to present-day understanding of volcanoes. Sadly, they died along with 41 others in 1991 at Mount Unzen in Japan as they observed the eruption from a nearby hillside.

Dosa spent months on a robust promotional tour after the film premiered at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival and began collecting awards. The documentary opened in theaters in July, began streaming on Disney+ last fall, and now streams on Hulu. The film is competing for a Best Documentary Oscar on March 12, along with three other Festival docs (All That Breathes, A House Made of Splinters, Navalny) and a film by Sundance Institute alum Laura Poitras (All the Beauty and the Bloodshed).

Still, Dosa is prone to deflect any spotlights on herself to her film team as a whole and to the subject. “Documentaries are less about what I have to say and more about listening to other people,” she insists. It all starts with the people.

She is drawn to the stories of unusual, fascinating, and passionate individuals. A friend and colleague, Josh Penn, who produced The Last Season, once confessed his rule of thumb when choosing the subject for his next film. He considers the “characters” and asks himself: Do I want to go on a road trip with these people?

“And it’s such a simple but powerful idea,” Dosa says. “It’s like, ‘Do you want to dwell in these people’s worlds? Do you want to see through their eyes?’ And the answer is yes, I am up for the adventure. I do want to understand the world as they see it, as they understand it.”

Similarly: “It’s important to me … [to] show the people in my film in a nuanced and emotional light, where the audience can really connect to them, feel empathy, and have a sense of understanding of who they are and what their story is.”

Most often, nature is a component in her films — a person’s exploration and relationship to nature, perhaps taking a “form of myth or a metaphor, or allegory, or magic realism,” Dosa says. Consider The Seer and the Unseen (for which she received a Documentary Film Grant in 2018 from the Sundance Institute), told through the eyes of an Icelandic woman trying to protect a threatened landscape and her family’s home through generations. The film addresses the power of belief in elves and other invisible forces.

Elves aside, telling stories about the environment and nature is “super important in terms of combatting very dangerous narratives about the alienation of humans and nature,” Dosa says. If she can in some way, any small way, contribute to mending that relationship, it would be hugely satisfying.

Dosa doesn’t dismiss the possibility of someday directing fiction films — just days ago, Searchlight Pictures announced it wants to make a narrative feature about the Kraffts with Dosa attached as a producer.

At the same time, she is supremely committed to documentaries: “I think documentaries are important to the world in profound ways.”

“Everything needs to be questioned,” she says. “I’m just very much a believer in that. I think the way that history is often narrated, from the perspective of the ‘victor’ — that’s maybe cliché to say, but it’s really true — there absolutely need to be spaces created to uplift voices that have been actively erased or left out for various reasons. And I think that space of documentary filmmaking can very powerfully do that.”

And Dosa cannot envision ever becoming bored with the documentary format.

She loves to learn, and she has learned much with every documentary she’s directed or produced. She treasures a deep collaborative process with her subjects and with her film team: “That’s always brought a tremendous sense of meaning, joy, gratitude — often hilarity,” she says.

“The process of learning and creating that documentary filmmaking provides is something I want to do until the very end.”

Now that she’s been nominated for an Academy Award, it’s not entirely absurd to begin thinking about a legacy. Still, she is slightly taken aback by the prospect.

“I think it’s important to live your values, which is harder to do than to say, but it’s something to strive for,” she says.

“But I think the first thing that comes to mind: I want to be known for working well with my teams and making work that we all feel like we can really stand behind… I think I want to be, maybe, remembered as someone who was awed by the power of a story and awed by the power of nature.”