For Native American Heritage Month, the Sundance Institute is proud to highlight conversations with former and current Indigenous Program fellows that focus on the bi/multiracial experience. Full Circle Fellows Anpa’o Locke (Húŋkpapȟa Lakota/Ahtna Dené) and Zoë Neugebohr (Odawa-Ojibwe) discuss their own unique experiences growing up in multicultural Indigenous households and how that shaped their experience and view on Thanksgiving.

Anpa’o Locke

Growing up, there were two different types of Thanksgiving. With my Native mom, it was a very radical and anti-colonial “celebration” of the holiday. My mother’s focus was making sure I understood the misrepresentation of Indigenous histories and perspectives. This meant making traditional Lakota foods such as buffalo soup, wozapi, and three sisters’ foods. I am not the greatest chef in the world so I have always watched (since my reputation for cooking isn’t the greatest). We celebrate with a meal and education.

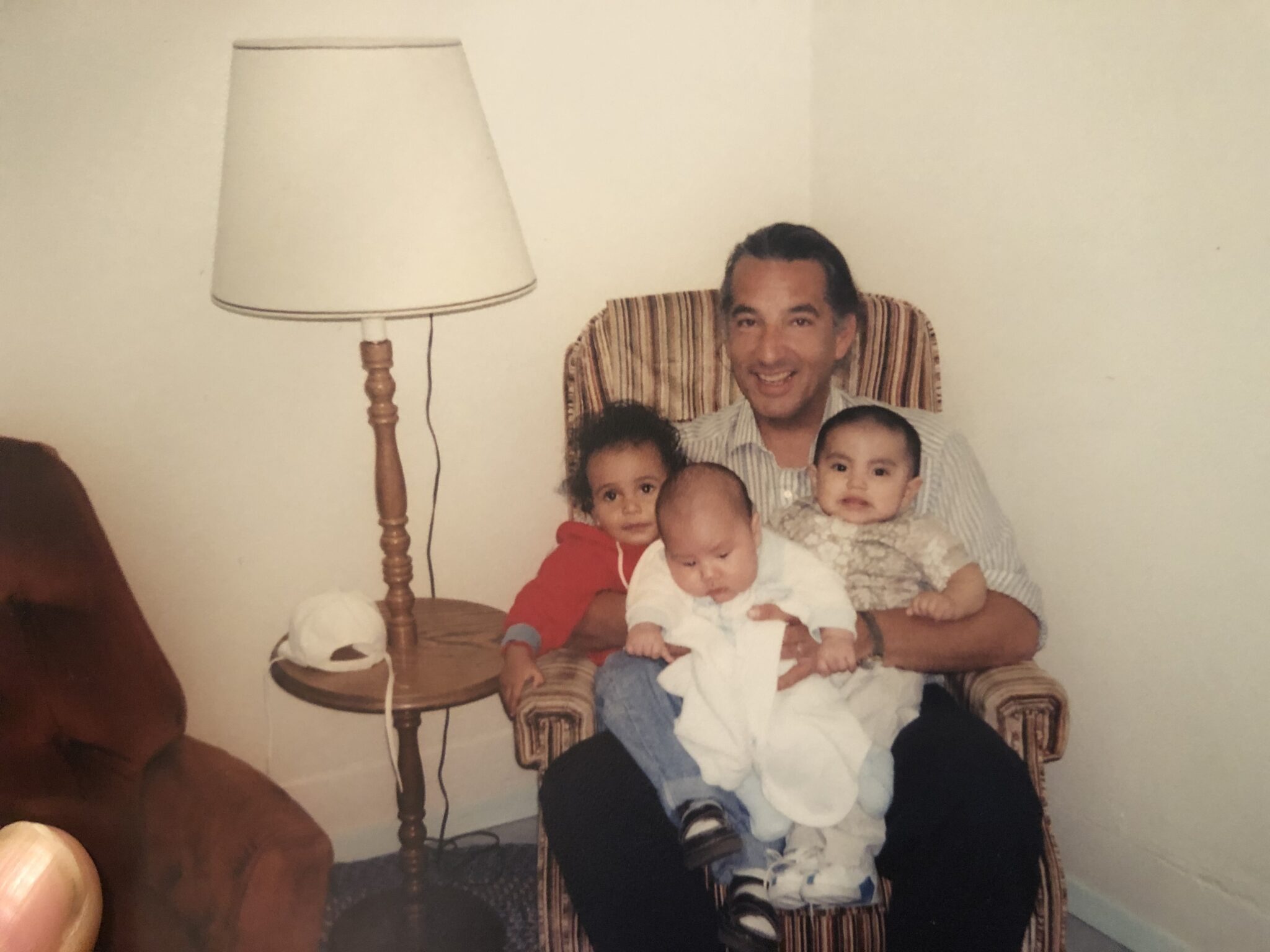

On the other hand, having Thanksgiving with my Black dad was a completely different experience. I would get the best Black soul food of my life. It would be filled with dancing, laughter, and a general sense of joyousness. However, I wasn’t holding the same type of conversations about Indigenous peoples because the focus wasn’t on Thanksgiving as a colonial concept, but rather a moment of reconnection with everyone. It was one of the few holidays where we could have a community gathering, see family, be surrounded by everyone all at once, and receive nourishment for the spirit and mind.

For both sides of my family, our gatherings typically look like a chaotic mess that is grounded in love. Our moments of being a community where we come together for connection instead of the colonizer’s understanding of Thanksgiving. Using traditional foods as nourishment for our bodies and allowing joyousness and understanding to be our central focus. Food is the way that has brought both my Native identity and Black identity together.

Zoë Neugebohr

Growing up removed from a culture tends to throw a bit of a rock in the attempt to create stability within your mind that you do indeed belong to the culture, whether you grew up around it or not. I was raised in Southeast Michigan, a bit far from my ancestral lands in Northern Michigan. When I was born, my mother had grown apart from my grandfather, the bearer of knowledge when it comes to our Anishinaabe traditions and culture, not reconnecting with him until a bit later in my life as a pre-teen. So, when it comes to holidays like Thanksgiving, in the process of reclamation, there are important conversations we have decided to have about how to shift from celebrating a mindless, frankly ignorant, American holiday to intentionally getting in touch with your culture on a day of remembrance. A big thing for my mother and I is cooking together. It has always been a centerpiece within our relationship since I was younger. On my dad’s side, I’m Jewish, so the culture and tradition of cooking is an easy connection between the two.

In the last few years, we’ve loved finding ways in which we can incorporate our ancestral foods into our big, familial meal of gratitude. Not only does this help us honor our ancestors in a loving, prayerful way for us, but it helps us learn a bit about our health as well. What kinds of foods work best for our bloodline? How can we honor that more on a day-to-day basis? Breaks from work and school around the holidays offer us the perfect opportunity to find ways to decolonize the time we spend together as a family and find our roots again, especially in the kitchen.

Anpa’o Locke

Aŋpétu Wašté. Háŋ Mitákuyepi, Čhaŋté wašté napé čhiyúzape. Anpa’o Locke na Tawačin Wašte Win Emáčiyape. Waníyetu aké má wikčémna núŋpa aké núŋpa. Wikȟóškalaka hemáčha yé. Íŋyaŋ Woslál Háŋ Hemátaŋhaŋ. Akíčhita Háŋska El Wathí. Philámayaye. Anpa’o Locke is an Afro-Indigenous writer and filmmaker, who is Húŋkpapȟa Lakota & Ahtna Dené, and she comes from the Standing Rock Nation. She is currently located on Tiwa territory in Albuquerque. She graduated from Mount Holyoke College with a Film Studies major, whose work has been creating films on the Native diaspora experience and a critical analysis of Indigenous activism and environmentalism. From 2018 to 2019, she was a fellow for AWAKE Youth Media Fellowship. AWAKE Youth Media created the fellowship after the Mni Wiconi protests; as a fellow, she finished and fulfilled a film project based on Urban Natives living in New York City. In February 2021, She won “Best Experimental” at the Five College Film Festival for her film, “Representation.”

She is curious and driven to create films focused on screen sovereignty and self-determination as a mode for empowered Indigenous storytelling. Working with Indigenous communities is one of the more essential aspects of her professional career as she sees herself as a creative community organizer. As a person who operates with an Indigenous worldview, being a good relative is a central ideology.

Zoë Neugebohr

Zoë Neugebohr is an Odawa-Ojibwe writer/director from Detroit, MI, currently based in Los Angeles. She recently graduated from the Film and TV Production program at the University of Southern California and is now working on writing her first feature.

Zoë, not having grown up on a reservation and a bit removed from her culture, looks to find ways to reacquaint herself with her indigenous roots and carry forth Odawa-Ojibwe traditions of storytelling within her own stories. She also wants to help inspire Natives in similar situations to her own so that they may find their own reclamation paths and voices to help carry on our cultures and traditions.

She aims for her films to explore the spectrums of indigeneity to show the world what indigenous existence and persistence truly looks like, despite many obstacles to get where we are today. In the further future, Zoë plans to study tribal law and pivot her work towards documentaries.

[Editor’s Note: This post was originally published November 29, 2022]