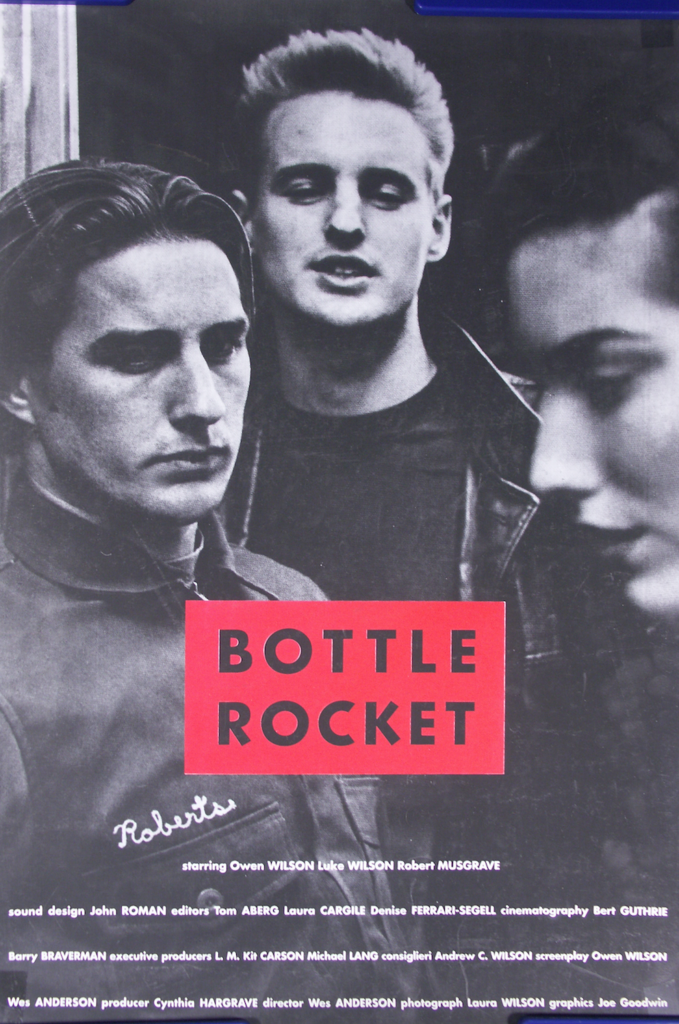

Wes Anderson puts up the poster for his new short film Bottle Rocket at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival.

by Laura Studarus

At the 1993 Sundance Film Festival, Wes Anderson premiered Bottle Rocket, a scrappy short film about two petty criminals planning the ultimate heist, only to walk away with a hundred dollars each. The black-and-white short contained hints of what would later become the director’s hallmarks: ragged emotional exploration couched in off-hand humor, stylized camera movements, self-aggrandizing characters, and the Wilson brothers. But no one could predict the legacy he’d craft out of these extremely purposeful building blocks nine more films and a handful of shorts later.

If there’s one criticism lobbed at Anderson’s work, it’s the lack of realism. But to reach for that complaint is to miss the point completely. These are modern fairytales, told by a man with so much enthusiasm for putting on a show, 2021’s The French Dispatch — a post-World War II story of a newspaper shuttering after the death of their beloved editor — moves through colorful set pieces and story vignettes as if we’re watching an actual play. Why reach for realism when you’ve got this level of old razzle-dazzle?

Emphasis on razzle-dazzle. From a sherbet color palette and symmetrical shots, to sets crafted with a hyper-attention to specificity, you know when you’re watching one of Anderson’s films. It’s a calling card so precise, his aesthetics have spawned an Instagram account aimed at finding equivalent real-world spaces, a memorable Saturday Night Live parody, and even an Italian café designed by the director where fans can caffeinate like one of his quirky characters.

Entering his hyper-specific worlds is incredibly appealing, whether it’s a house populated with geniuses (The Royal Tenenbaums), a train trip through India (The Darjeeling Limited), or a run through the history of a stately resort (The Grand Budapest Hotel). How often are you offered such hermetically-sealed, escapism-rich environments, free of real-world chaos and product placements? (Save for his 2013 short film collaboration with Prada, Castello Cavalcanti.) Anderson knows his strengths lie in idiosyncratic visuals, just as much as anything else in the script. (Most of which he also co-writes.) It’s no accident that the first act of most of his films include a tour through characters’ living quarters and daily routines as a narrative warm-up. At this point it’s become both storytelling and a well-deserved victory lap.

The stories he tells are also a direct contract to his characters, gloriously intense people, often on the verge of either a breakdown or breakthrough, that could never exist — let alone survive — outside of his precise worlds. Rather than rom-com-style resolutions or Hallmark-like sap, we’re handed the pieces of their desire and asked to put together the puzzle ourselves. That means sifting through beautiful moments that don’t quite add up, subtext-heavy dialogue, and — if we’re very lucky — a narrator who will remind us that people rarely say exactly what they mean.

However, Anderson isn’t bashful about showing us exactly what’s haunting his characters. Chas Tenenbaum might have not had the words to describe his childhood alienation, but the Dalmatian mice he created as a precocious, misunderstood teen still scurry through the house he left behind. Jack never fully described what he was running from, but in Hotel Chevalier, the short film sequel to The Darjeeling Limited, we watch along with Natalie Portman (in full Jean Seberg mode) as she scours his packed Paris hotel for clues. And the emotional release of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou comes not from getting drunk and killing the shark that ate Esteban, (as Bill Murray’s titular character predicts), but rather looking the creature in the eye, and realizing life is much bigger than he had ever imagined.

We have been shown, rather than told. Anderson’s films are often rejected because his narratives never feel fully tied up, instead being left artfully frayed. His characters are changed for the better, but never dropped at their final locations. Which is fine — the lives they lead and the beautiful playgrounds they inhabit, live on in our heads, long after the final reel.