By Vanessa Zimmer

Welcome to part three of our four-part series introducing the short films and their directors from the 2022 Sundance Film Festival Shorts Program — access to which is just one of the perks of joining a like-minded community of independent film-lovers.

All Members of the Sundance Institute get their own private screenings, from the comfort of their own homes, of these 12 short films from past Festivals. If you’re not a member and join by July 18, you can also receive access to this curated selection.

Last week, we covered three short films, The Fire Next Time, Five Tiger, and The Fourfold. (Click here if you missed it or want to review.) The first blog introduced the 2021 Short Film Jury Award winner Bambirak, as well as the charming BJ’s Mobile Gift Shop and the alarming Excuse Me, Miss, Miss Miss. (Click here if you missed that blog or want to review it.)

The Sundance Film Festival Shorts Program, presented by XRM Media, allows Members online access to watch the collection, which also includes UnLivable, Forever, and White Wedding.

And that’s not the only benefit of joining. Membership also offers invitations to in-person private screenings, early access to Sundance Film Festival tickets, and more ways to stay connected with other Sundance-supported artists throughout the year.

Read on to learn about three more films in the collection.

Mountain Cat, written and directed by Lkhagvadulam Purev-Ochir

A young Mongolian girl is taken into the rural countryside by her mother, who seeks a blessing from a shaman they call “Grandfather” so that the ailing girl will survive a life-threatening heart condition.

Feeling hesitant from the outset, the young girl feels exploited by the shaman, whom she observes after he has removed his robes and headpiece to be a man as young as, or perhaps younger than, herself and wearing a man bun. Her mother has left the family’s hard-earned mo

Purev-Ochir says Mountain Cat was inspired by a real-life personal experience with a shaman: “Shortly after the grim ritual with the Elderly Spirit finished, I came upon the shaman who had taken off the ceremonial

robes and headdress. I was shocked to find someone not only younger than me but also someone sporting tattoos and earring on one ear.”

“I found out that he had become a shaman a few years before when he was still a teenager,” Purev-Ochir continues. “Remembering how my own adolescence was filled with teenage turmoil, I tried to imagine how my life would have been if I had been a shaman at the same time. Being a shaman brings a host of new problems, obligations, and emotions on top of the usual growing pains.

“This short film and the feature film connected to it are my way of exploring modern-day Mongolian youth, as well as the dual identity that we carry as a people with strong ties to our history and tradition but with a razor-sharp focus on progress and becoming ‘Western.’ ”

Purev-Ochur says it doesn’t matter that the young woman doesn’t believe in shamanism: “Shamanism is a way of life and doesn’t require belief. It’s a way of orienting oneself within the universe, especially in regards to nature… And regardless of what she believes, my intention was to show that shamanism exists to the present day because its topics of concern are perennial topics.”

Purev-Ochir is developing a feature film on the character of the shaman and his adolescent and spiritual turmoil.

Raspberry, written and directed by Julian Doan

An older man’s labored breathing is the only sound on a black screen as the opening credits roll, before any characters appear on screen. Then the wife and adult daughter and son are shown standing bedside in tasteful street clothes, tearfully clutching one another once the breathing stops.

“Your father has left,” sobs the wife. Across the room, sitting in a chair near the door, is a silent and uncertain younger son (Raymond Lee), in stocking cap, T-shirt, hoodie, and shorts.

The short film, written and directed by Julian Doan, is mostly about how this young man chooses to say goodbye to his father. At just over seven minutes in length, with only three minutes of dialogue, the film’s emotion is primarily conveyed in the faces of Lee and the

others as two undertakers arrive to take their father away.

“During the shoot and even months into the edit,” says Doan, “I felt my face contorting whenever I watched (Lee’s) moment; there’s so many emotions twisted up in just seconds of screen time. We were floored.”

“I wrote it very much how I pictured it being cut together, and tried to build the speed into the writing,” adds Doan. “When the son walks into the room for his turn to say goodbye, I imagined it being like man stepping on the moon for the first time, like this arduous journey that, in fact, only covers like 8 feet.”

The grief of the young son and the rest of the family contrasts with the gentle but rote, business-like tone of the undertakers. “The story is based on the very real experience of literally watching my dad take his last few breaths one morning,” Doan explains. “It was incredibly anticlimactic, which made it very surreal, and I wondered what I even expected; so I wanted to capture that feeling of utter mundanity that I think few people are ever prepared for.”

Doan says he wants to convey to audiences the utter complexity of losing someone you love. He hopes Raspberry “prepares them for the reality of what it means to experience death — that it can be deeply tragic, painfully funny, and just really damn normal.”

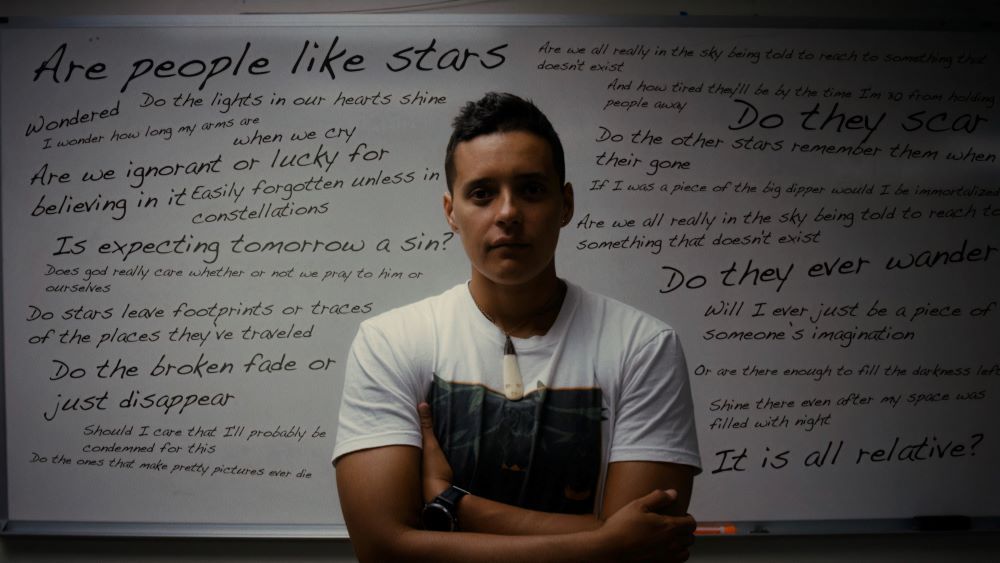

This Is the Way We Rise, directed by Ciara Lacy

Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio found a renewed voice on dormant Mauna Kea, Hawai’i. And fellow native Hawaiian, director Ciara Lacy, tracked her down to tell the story. What they create together packs Osorio’s earnest slam poetry and natives’ burning loyalty to Hawaiian culture into an affecting 12-minute film, The Way We Rise.

An activist and an assistant professor of Indigenous and native Hawaiian politics, Osorio early on realized that people listened if she expressed her views on the exploitation of Hawaiians and their land through a poem — and presented it through a dynamic, powerful performance: “If it doesn’t bring a tear to your eye, if it doesn’t conjure a memory, if it doesn’t give you chicken skin, the poem is useless to me,” she says.

Lacy says she had been following Osorio and her work. “I have a soft spot for poets and performers, and met her through friends,” she explains. Osorio had also heard of Lacy; the assistant professor used Lacy’s film Out of State, about native Hawaiian prisoners incarcerated in Arizona, in her classes. “So there was an immediate connection as fellow Hawaiians doing work in the community,” adds Lacy.

The film focuses on Osorio as a member of a group who chained themselves to a cattle guard near Mauna Kea to protest the construction of what would be the 14th telescope on the mountain — a peak that is considered sacred by natives. The experience reinvigorated her: “Being there, I had a voice again, I had something new to say.”

Activism also runs in Lacy’s family. “As a native Hawaiian, the protection of sacred sites is a responsibility,” she says. “This is something I learned from my own mother, who along with a small collection of women, moved into Halawa Valley on Oahu in the ’90s to protect sacred sites.

“In many ways, that activism shaped me. So, today, when I see the collective action in protection of Mauna Kea, I feel a connection to the people willing to set aside their time to do what they feel is right.”

What to Watch: 10 Films Led by Strong Characters to Screen During Women’s History Month

Film Festival Watch: The 22 Sundance-Supported Projects Showing at SXSW Film Festival