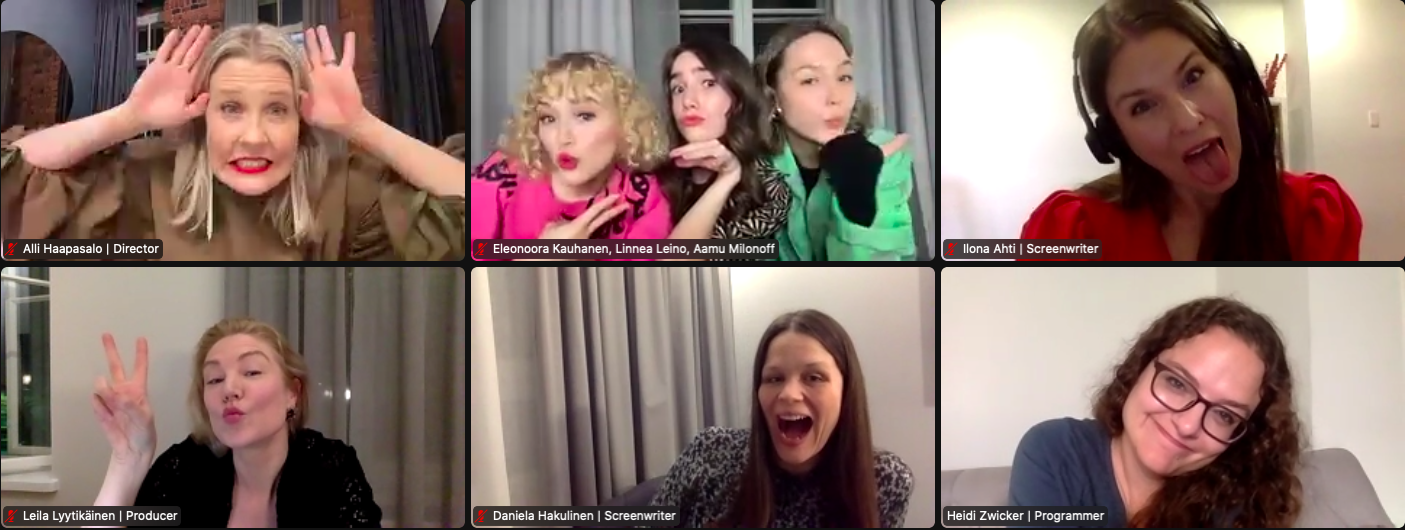

By Katie Small

Finnish director Alli Haapasalo wants to reclaim the word “girls.”

“I love the term ‘girls’ — it’s a very positive word for me,” she explains during the post-premiere Q&A of her film Girl Picture (whose Finnish title, Tyttö Tyttö Tyttö, translates to Girls Girls Girls).

“I’ve been told by some people in the beginning of this process that I should say ‘young ladies,’ but I just want to explain that I use the term ‘girls’ with a lot of empathy,” Haapasalo says. “If they think that ‘girls’ is belittling, I say, ‘I want to take it back!’ I don’t want ‘girls’ to be belittling — I think there’s nothing negative about that term,” she explains with a smile.

Haapasalo’s free-spirited exuberance is reflected in her film. Set in Finland and taking place over three consecutive Fridays, Girl Picture follows three college-age women as they navigate the liminal space between childhood and adulthood. The energetic coming-of-age film is an intimate fragment-of-life character study of young love and female friendship, delivered via the amplified, complex emotions of teenage life.

Best friends Mimmi and Rönkkö are the closest of confidants, divulging their sexual frustrations and romantic aspirations while working at a smoothie kiosk in a Helsinki shopping mall. The volatile and edgy Mimmi begins a sudden romance with Emma, a driven but repressed figure skater with a disciplined training regime.

Meanwhile, the whimsical and playful Rönkkö awkwardly navigates an ever-expanding dating pool of young men, determined to experience sexual pleasure. In one of many memorable scenes, she breaks out of her native Finnish to coquettishly proclaim, “I came to come!”

Girl Picture is as charming, sweet, free spirited, and fun as its main characters. It explores female sexuality without relying on trauma or danger to spur the plot, which Haapasalo says was intentional. “We’re so accustomed to girls on screen being seen through other people’s eyes,” she explains. “We’re used to seeing girls defined by boys, defined by adults, or representing a one-dimensional character that’s serving the story, be it the spectator, the woman who asks questions so the man can answer them, or girl-as-victim. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen many complex stories of girls center-stage, on their own terms, as their own strong subjects.”

Screenwriter Daniela Hakulinen chimes in: “We had the realization that many times we see teenage girls as victims or in danger in a man’s world. We wanted to avoid that. We wanted to give them a safe place to experience and explore themselves.”

“It was really important for all of us to have that world Daniella mentions, which is a world where girls don’t get in a dangerous situation,” Haapasalo adds. “In Finland we have a cliche, almost a joke, about all the TV series that start with a female body dead on a beach somewhere, and that’s where the story begins. We [made] the choice that in this world, there are no predators.”

In the film, all sexual situations are initiated by the girls themselves. “We all know that women are often seen as objects in film, but, even when they’re subjects, we still see them as nymphomanicas or women whose desire is punished by suicide in the end. Lolitas or hookers or whatever else,” Haapasalo continues. “I can’t name very many films where women are just exploring [sexuality] as a normal, sometimes problematic part of life.”

Girl Picture’s refreshing, honest, joyful take on sexuality allows its characters to explore their desire with impunity. “Sexualtiy belongs to absolutely everybody,” Haapasalo says. “The so-called ‘good girl’ is also a sexual being — everybody should be able to explore their sexuality freely and safely.”