by Matthew Eng

In the opening sequence of Joyce Chopra’s 1985 Smooth Talk, three teenage girls wake from a late afternoon nap on the beach and hitch a ride in an older man’s pickup, lest they be caught straying out of bounds by the mom assigned to fetch them from the mall. The coming-of-age drama that follows could conceivably follow any one of these characters. But it’s Connie, the long-legged blonde in the group, whom we’ll ultimately get to know. She’s the one who insists on riding solo in the flatbed, who throws her hands up in the air as they hit the road and serenely watches the sun set, western wind in her hair, as the trio hightails it homeward. She’s unforced and unburdened, just one of the girls.

She’s also, unmistakably, Laura Dern. Chopra’s first narrative feature, which earned the Grand Jury Prize at the 1986 Sundance Film Festival, marked the actress’s first starring role after several years of supporting parts. A year before, Dern proved so convincing as a sightless, lovestruck adolescent in Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask that when she showed up to shoot David Lynch’s Blue Velvet not long after, her co-star Isabella Rossellini proceeded to guide Dern around the set, believing she was actually blind. (Barbra Streisand also allegedly asked Bogdanovich, “Where in the world did you find a blind girl who can act?”) This story speaks to the immensity of Dern’s dedication to her roles — a value ingrained in her by two consummate, Method-trained character-actor parents, Diane Ladd and Bruce Dern — but also to an ingenuity that only looks ingenuous, an artfulness under the cover of effortlessness.

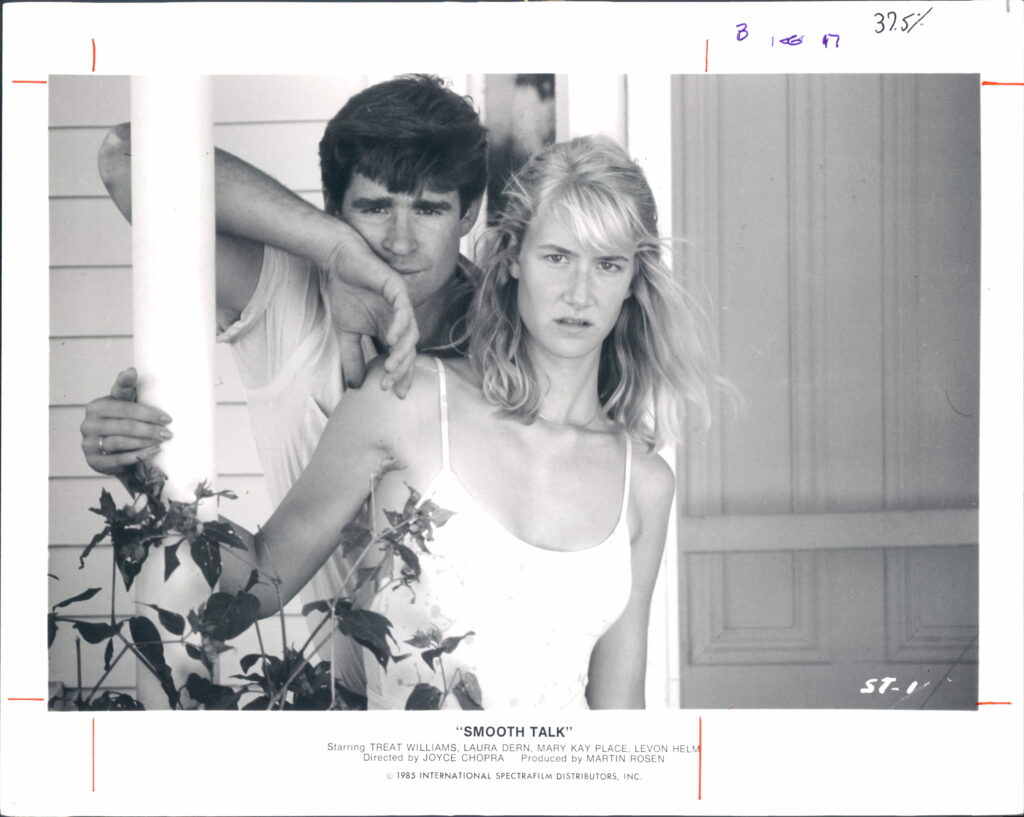

No early effort of Dern’s encapsulates this quality quite as vividly as Smooth Talk, a potent and perceptive adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ 1966 short story “Where Are You Going? Where Have You Been?” Part of a bumper crop of homegrown American indies helmed by women in the eighties, Smooth Talk heralded the arrival of an angular and energetic screen presence in its leading lady, who won the role days before production began after a friend of producer Martin Rosen spotted her on the beach in Malibu. Chopra’s film follows Connie, its 15-year-old heroine, through a formative, hormonal summer in her small Northern California town before her sophomore year of high school. She feuds with her fed-up mom (Mary Kay Place) and starchy elder sister (Elizabeth Berridge). She dons low-cut tops, sneaks into a roadside joint, and rides in cars with boys for the first time, thrilling to their tender attention. And then, when Connie’s home alone one afternoon, a hunky and increasingly hair-raising stranger (Treat Williams) shows up at her doorstep and insists on taking her for a drive in his gold convertible, the teenage dream of a gentleman caller warped into a waking nightmare.

Dern not only appears in every scene of Smooth Talk but it’s her character’s mercurial moods — her goofy, aroused, and sullen states — that determine and alter the tenor of these scenes. This would be a mighty undertaking for any performer, especially one tackling her first lead role. But Dern is innately comfortable and confident in front of the camera. In the film’s domestic scenes, her casual line readings and relaxed bearing suggest an actress conscious of what the camera requires of its subjects in a given moment, permitting her to simply be within the confines of the frame and, in doing so, become Connie. Elsewhere, Dern is gleefully, simperingly insolent, sprinting through the mall, blowing through stores, bending her body over the escalator handrail to ogle the bulges and backsides of the guys eyeing her. She makes us understand how much of our teenage years are spent strenuously delineating separate lives, the one we present to parents and the one we unleash on the rest of the world.

As Connie embarks on her romantic escapades, Dern’s unvarnished realness grounds Connie without idealizing her. She is neither a temptress nor a babydoll but an average girl in the midst of an awakening. There is a moment when Chopra trains the camera on Dern’s pellucid face in close-up as Connie recounts her recent amorous encounters. The actress delivers this monologue in a trancelike state, imbuing these memories with a warm-blooded, soft-spoken earnestness so profound that the viewer may very well blush. Dern’s rising intensity cuts straight to the core of Connie’s need to be embraced, sung to, cherished. Dern holds Connie’s dual selves at once—balancing the girl eager to experiment with the girl who has adorned her bedroom walls with James Dean posters and dances with ungainly pep to James Taylor (who served as Smooth Talk’s music director), no matter who’s watching. The actress captures and conveys all of Connie’s contradictions, her need to break away from her mother’s stern rule and, at the same time, be accepted and loved by her harshest critic, to be a worthy daughter in her eyes.

Dern was seventeen when she played Connie and hardly removed from the incidents and feelings depicted in the film. She had graduated high school the year prior after doubling up on classes and was living on her own for the first time, having gained legal emancipation in order to work adult hours. (Her roommate at the time was future presidential candidate Marianne Williamson.) Smooth Talk demanded a great deal of Dern, who has established herself as one of the screen’s most emotionally unfettered stars, capable of enacting a character’s complete transformation on her iconically pliable visage. When Dern expresses herself at full-throttle, she is without peer. In one scene, Connie gets stranded at the mall after hours without a ride to be found and Dern’s nerve-splitting panic makes the moment feel downright cataclysmic. At night, when shooting had wrapped for the day, Dern found herself alone and discouraged in her hotel room, thinking, as she recounted for Buzz Magazine in 1991, “‘I know that we’re doing something good here, but I’m feeling so much pain.’” But the work itself—the life being created on set, for the camera—excited and inspired her. “I learned what my parents had known for a long time, which is that what actors do is quite extraordinary,” Dern said. “As an actor, you can take experiences in your life and qualities in your nature and use them to explore and learn about yourself and other people… figuring out why we do what we do.”

The centerpiece of Smooth Talk is the lengthy tête-à-tête between Connie and Williams’s predatory Arnold Friend. Dern is indivisible from Connie across these twenty-five minutes, passing through modes of intrigue, alarm, petrification, and docility, sobbing and stretching her mouth into a ductile grimace as Arnold intimidates Connie into taking a ride with him, the details of which are decisively left off-screen. And yet, even within this final moment of submission, Dern injects nuance into the proceedings. As Connie gets into Arnold’s Pontiac, Williams coos, “My sweet little blue-eyed girl,” and something in Dern’s deportment stiffens and strengthens. “What if my eyes were brown?” she scoffs, making this ironic response into a tiny act of defiance amid the psychosexual terror.

Even as Connie stares down the Big Bad Wolf, Dern endows the character with fragility and fortitude, her vulnerability coexisting with her moral fiber. In the final scene of Smooth Talk, Connie, unsure how to process what occurred on the drive with Arnold, shares a dance with her sister. In this rare moment of communion between sisters, Dern’s face plays out an inner struggle, fighting back a memory or just a tremor of something darker. Her eyes are newly open to the world and its masculine dangers. And our eyes are locked on Dern, here and evermore.