[Editor’s Note: This interview is part of a larger feature about the women documentary filmmakers who blazed trails for the craft by premiering their films at the Sundance Film Festival in the 1980s. Please read the main introduction to this feature here.]

By Bedatri D. Choudhury

You are currently restoring the film but tell me what made you want to make it, back then?

PDK: When I was in art school, I remember a teacher took me aside and he said, ‘You have talent, but you really need to marry, stay home, and raise children.’ This was in 1972. And I was so shocked. Here he’s teaching at Pratt Institute, and you have men and women working together. We were looking at the women’s movement, and here was this very blatant expression of sexism. One of our producers, who has since passed away, Lynne Campbell founded Women Against Pornography in in Manhattan. Lucy and I, and a bunch of women were able to go through 42nd Street, and visit the sex shops. While women’s voices were censored, we saw pornography and these expressions of exploitation. We believe in First Amendment rights, but you don’t want to be surrounded by these images and this kind of abuse. And so we realized we wanted to find out the roots of sexism, and other forms of oppression, racism, and exploitation of women. We wanted to cover the ground and show that there’s a continuum. What is being said in sexist images of women in advertising, in pornography, is perpetrating violence against women in real life.

LW: There was so much hurt and anger in a moment like that. We were raised with lip service being given to ‘you can do anything, and the sexes are equal.’ And that as a woman artist, you have every opportunity that a male artist does. That was absolutely not the case. That was a really rude awakening.

We went around and interviewed men who produced images that we thought were sexist. And asked them what they’re doing, and why they’re doing it. And the answers were not surprising, except in their honesty. As Paula pointed out, the values that informed the mainstream advertising, and the men who put that advertising out in the world, were the same values that we found in the pornography shops. Same values expressed in a more extreme way.

That must have been a hard film to make?

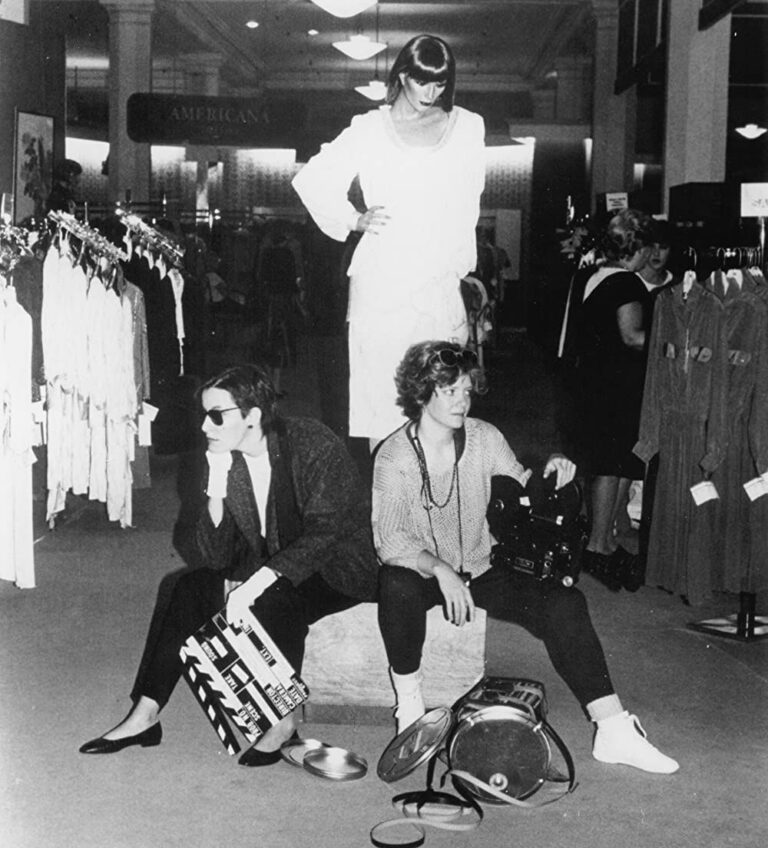

PDK: In some ways, it was kind of easy as well. We bought a 60 millimeter camera with another woman, and we shared it around. It got a lot of use. It was sort of like guerilla filmmaking; we just went out there with our lights, extension cords, and an old secondhand Nagra tape recorder.

This is all to say, with very little money, we had great freedom. We rented a Steenbeck editor, and Lucy edited the film. Then we got some money from British television, $30,000 or $40,000. Which meant we could actually buy the Steenbeck and put it in Lucy’s living room.

What would you say has gotten easier down the years?

LW: Technically, the thing that has made the biggest difference in terms of the making of the film is nonlinear editing. I am sentimental about cutting celluloid but the ease with which you could lose a frame of film was horrifying. I don’t think anybody who hasn’t done it, can imagine how different it once was.

The film is going to be rereleased. Back then, we simply released it, and it was very successful, and also very controversial. Now, we are all feeling like the film might not land perfectly with younger audiences. And of course, we want young women and young men to see the film, and that it requires some context to let people know what we’re about. So I find that shift to be fascinating. This adding of some context so people are prepared for what’s to come.

PDK: It really was amazing what we got away with!

How was the film received?

LW: I would say overall in the progressive left art world, we got enormous praise and fantastic reviews. But in settings like Sundance — we are very grateful to them for programming our film and funding the restoration — I remember feeling sad that it wasn’t more warmly received, that there was a kind of a reservation.

Do you remember some of the criticism?

PDK: That we were being sexist by not having any women in the film.

LW: I had forgotten about that! That was not the point. Yes, both sexes are sexist but we wanted to understand this situation. The male sex was the dominant force. We wanted to find out what their motives were, what their values were, what their understanding was, what their perceptions were.

Were you ever thinking of making money when you made the film? Wondered who would buy it?

LW: Well, no. Actually, let’s circle back just a moment. It was beyond us to imagine that we could actually do this. That two women, two lesbians could be making independent movies that the public would see. Absolutely beyond belief. We didn’t even know if we could finish. And then if we finished, would anybody look at it? Let alone find value in it. That was beyond our wildest dreams. But that happened, and that was extraordinary. On a certain level, as a young filmmaker, I just said, ‘If we can just finish this movie, and if anybody watches it, I will die happy.’ I think it’s really important to take into account just how outrageous it was to make a movie.

PDK: When the film was made, it was this feeling of relief. Because it was done and I could go ahead and be a limousine driver and earn good tips! I thought I certainly wasn’t going to have a career in films but I loved experimental films. And just to be able to have a little Motorola and to look at my experimental films, that was wonderful. And I was very satisfied to do that. But we were really struggling artists, starving artists. And that has changed. Goodness knows, there’s some wonderful independent films now. And the generation of young filmmakers are getting attention, and it’s so beautiful to see that.