[Editor’s Note: This interview is part of a larger feature about the women documentary filmmakers who blazed trails for the craft by premiering their films at the Sundance Film Festival in the 1980s. Please read the main introduction to this feature here.]

By Bedatri D. Choudhury

Your first feature made it to the Sundance Film Festival and then had an Oscar nom. What was that like?

We really got lucky with that film. I have to say, I was so young that I didn’t quite get a lot of the hoopla. I was 29, which was pretty young back then because people making documentaries were all older. I made the film with Christine Choy who was older. It was exciting!

What do you remember from that first Sundance Festival?

I was living in New York but was in LA during the weeks before the Festival to shoot a new film. My LA-SLC flight was booked, lodging was fixed — we were going to be sharing a house with Stephen Soderbergh, and I was going to return to NYC after the Festival.

Then I happened to meet a guy in LA, Armando and we went out a few times, and there was something about him. I knew if I went to Park City, I’d end up back in NY and would never see this guy again. So, I decided not to go to Sundance and stuck around in LA to see where the relationship would go. Every twenty-something female filmmaker I’ve ever told this story to is aghast. I’m aghast when I tell myself.

But we’ve been married forever and have a kid and two cats. Professionally, not all was lost — my film Calavera Highway that was on POV is his family’s story. I did go to the Sundance in Tokyo festival with the film, which was a blast. I love festivals as much as the next filmmaker and I know how important these venues are to your career, but I will say that sometimes it’s a drug you don’t have to take.

Would you say that is a kind of privilege, though?

Yes, that was a big luxury for me to choose not to go to these festivals. I think about Set Hernandez who can’t go to screenings outside the U.S. for Unseen because of their undocumented status.

You’ve been steadily making films since. What’s changed?

There has been a very logical trajectory of resistance and organizing. That’s been going on since before I even joined the business, of course, but things are much more open now. People have crashed through the gates, but it all goes back to organizing over the years. People at Visual Communications… at Brown Girls Doc Mafia… they bring people to festivals. The same thing was done in the ’80s, but at a much smaller scale, we had less power. But that was the foundation.

The organizing now has become professionalized. It’s an effective advocacy space and it’s organized and professional, and that’s very good and very powerful. People have to make a living while making films that make change happen.

There is so much that’s said about Oscar campaigns and how expensive they are. Did you have one?

We didn’t have an Oscar campaign. Yes we submitted the film, things were very different back then. We didn’t take out ads, we didn’t know who was on the committees, who the members were. There probably were very few women. I remember in the 1980s, I thought that to get nominated, just finishing a feature length film was enough. It was so hard to do a feature length film, that I thought making one automatically bolted you into these possibilities.

But the real question is not when an Asian American film documentary has a campaign, but when did an Asian American documentary have a theatrical release? So if you look at the ’80s, the ’90s, and the early 2000s, there were very few Asian American films that got a theatrical release. And the theatrical release, of course, was dependent upon things like getting into Sundance or getting into Cannes, or whatever. So the gates were closed at every single step.

We’d be lucky if Karen Cooper took the film at Film Forum, or the Laemmle on the West Coast. But they weren’t taking a lot of our films. I guess, the equivalent now is the market for streamers, who only buy a certain kind of documentary.

What advice do you give to younger filmmakers?

I was talking to a young filmmaker whose film got into a few film festivals but they got dozens of rejections. And I said to them, ‘Your film is going to have such a long life, because it’s the only film about that subject.’ People will want to see that film. Programmers may not like a film, every film will not have a festival life. But then, for years and years, people will watch it because there’s an audience that wants to connect to the story, to the issues. It’s completely ok to separate that audience from the audience of cinephiles and festivals. Everybody wants to have a career, everybody wants to sell their film. But you know, that’s not necessarily the way to get the film to the people who you wanted to make the film for in the first place.

I’ve been making films for almost 40 years and I’ve been fairly successful. I can’t survive without a day job. Some people are better business people, some people come from money but I have never inherited a penny.

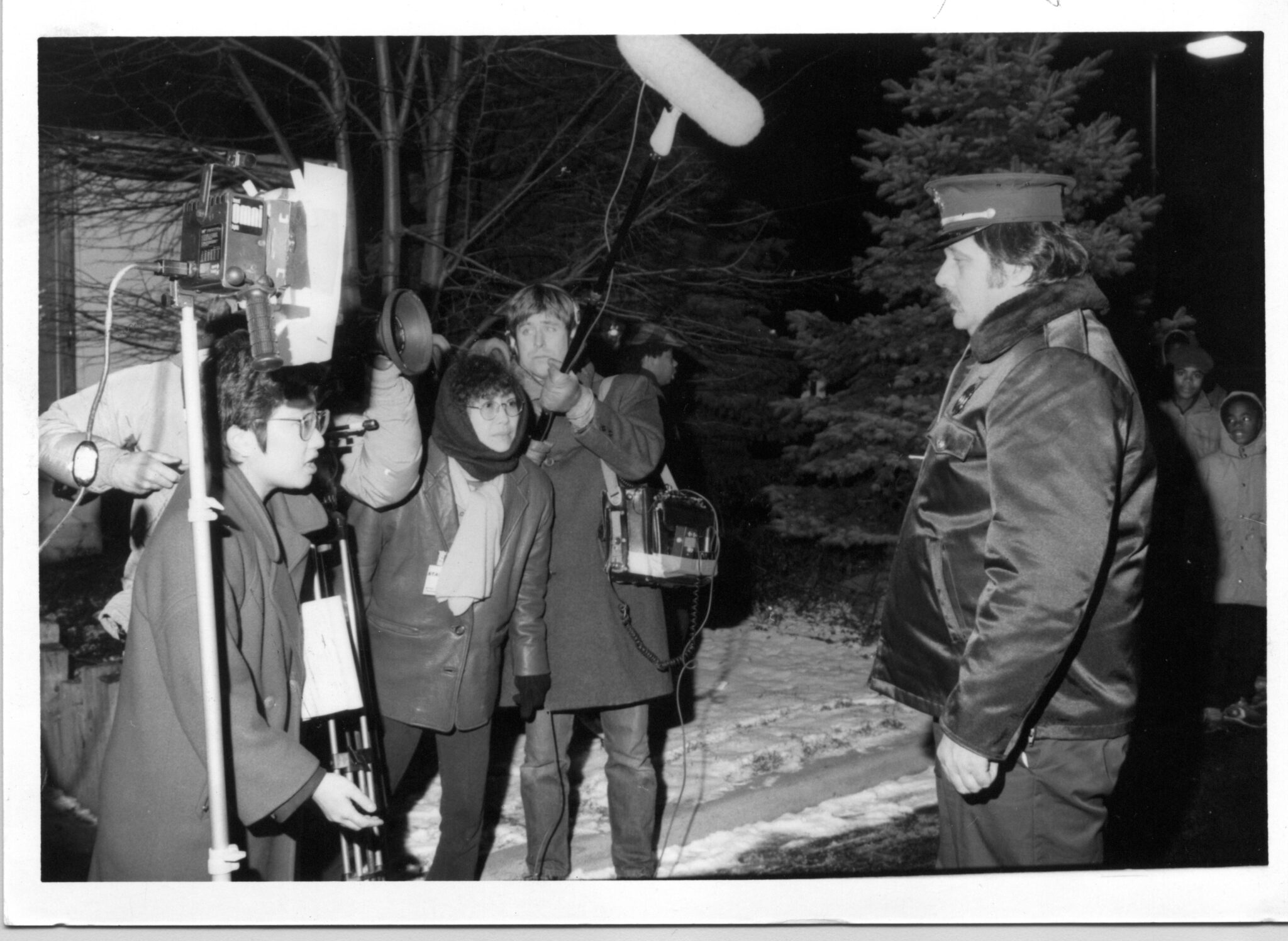

Why did you make Who Killed Vincent Chin?

Oh, the story pissed me off. When we first heard about the story we thought, ‘OK another racist person’ but when you look at the story in a deeper kind of way, it was infuriating. We went to Detroit for three months and it really blew my mind because there was so much nuance to the story that I didn’t realize. Every time we approached something, it got deeper and deeper, there are layers and layers, and that’s kind of the beauty of a documentary. Finding those layers. The Vincent Chin case was a social movement, involving community people, but also young journalists, the legal and civil rights organizations; they were also very young. And so the young attorneys got involved, so we were really looking at systemic racism within the ecosystem, which we were resisting. But then resistance is also an ecosystem. So you can see how that ecosystem mobilized during that time, but then, over the next 30-40 years, it had its own kind of activist trajectory.

But yeah, I did it because it just pissed me off. And now I want to make a million films because I’m in a constant state of rage.