Claiborne Smith

You hear something often enough, and it starts to seem true. And as the directors of Russian Lessons have known for at least as long as the Putin administration has been in power, when you’re part of the government-allied Russian media, people believe what you say even if it is rather strange.

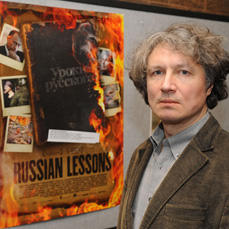

As becomes immediately clear in Russian Lessons, investigative filmmakers Andrei Nekrasov and Olga Konskaya, the husband-and-wife directors ofthe hard-charging documentary, are not part of the mainstream Russian media. In August of 2008 they kept hearing on Russian TV that Georgia, the tiny U.S. ally at the bottom of Russia’s southwestern edge, had attacked its own region of South Ossetia, whose people have consistently allied themselves with Russia despite the fact that Georgia declared its independence from Russia in 1991 as the old Soviet Union was dismantling.

Mainstream Russian journalists kept saying that because Georgia had attacked South Ossetia, the United States had thus attacked Russia. “What concerned me was the amount of lying that was going on,” Nekrasov says. “I find it really off-putting. Some cynics say, ‘That’s just the style of [Putin’s] regime,’ but it’s not a matter of style; for every lie, there’s a lot of suffering out there.”

Splitting up to better cover what became known as the Russia-Georgia War, Nekrasov and Konskaya quickly document—through determined, old-fashioned gumshoe reporting—that Russia had moved its tanks into Georgia well before the conflict began, throwing into question Russia’s claim that it had been attacked and suggesting that Russia stoked the war to permanently move its troops and war equipment into the territory of its enemy.

“You can’t make films about all aspects of life,” Nekrasov points out. “As a filmmaker, you inevitably focus on the things that absorb the most important issues. And I just so happened to be in a place where the stakes are at their highest.”

Nekrasov and Konskaya met in Frankfurt, where Konskaya was acting in a Chekhov play produced by a Russian theatre company. Nekrasov had a layover and went to see the play with a friend. Their relationship eventually encompassed love, work, and now death. Konskaya died from cancer on May 28, 2009; she had been editing Russian Lessons as late as four days before she died.

“We were more than just partners in life—we shared everything: love for each other, love for our work; our work was our baby,” Nekrasov says. “She had that deadline in the most literal sense of the word and she wanted to finish it. She wasn’t spending her time watching spring; she spent it in the cutting room.”

Nekrasov, who has screened his films at the 2002 and 2004 Sundance Film Festivals, says that although “there’s nothing like a sense of good citizenship” in Russia, and thus no incentive to question the dominant Russian media, “there is hope that the Russian people can be moved” given the two successful small screenings he has given of Russian Lessons, one in Moscow and one in St. Petersburg, where he lives. The other reason Nekrasov has hope is perhaps more cynical: The Russian government doesn’t feel as threatened by its political critics as it does by wealthy enemies. “It’s a state mafia that really looks after their own interests and gets serious and violent when there’s a big threat to big economic interests,” he says. “That’s why I’m still alive, because I’m an ideological enemy, not an economic one.”