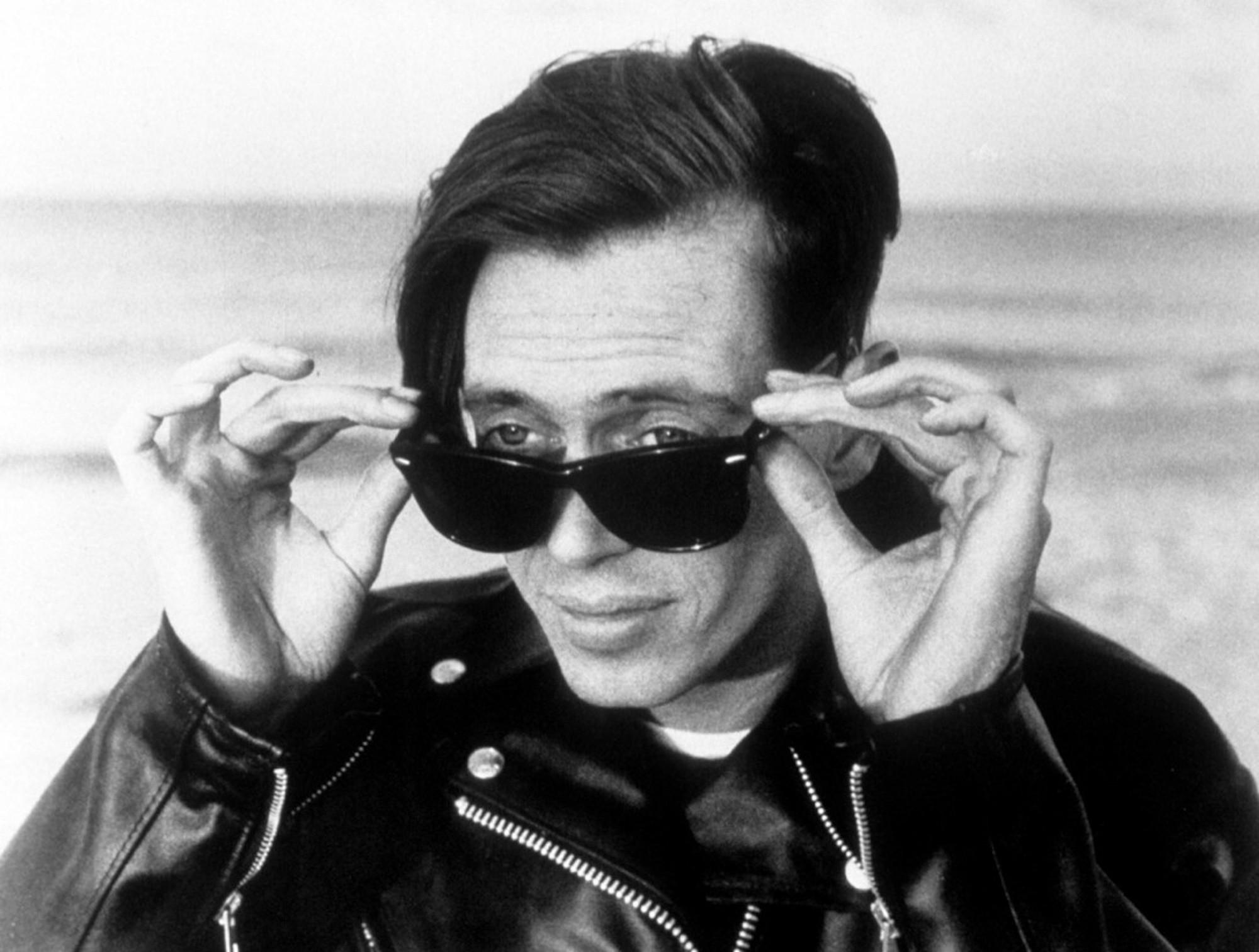

Parting Glances. 1986. USA. Written and Directed by Bill Sherwood. Courtesy First Run Features

By Matthew Eng

Parting Glances is at once an introduction and a valediction. Made for just over $300,000, this landmark of New Queer Cinema is the lone feature of writer-director Bill Sherwood, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1990 at the age of 37. Set at the height of the epidemic and unfolding over the span of 24 hours, the film follows a Manhattan social circle of gay men and the straight women who dote on them. The group has gathered together on the eve of rupture: Michael (Richard Ganoung), a stymied writer, is preparing to part ways with his boyfriend Robert (John Bolger), a bureaucrat for the World Health Organization about to embark on a two-year assignment in Africa. Sherwood’s debut earned critical praise (and Special Jury Recognition upon its premiere in the U.S. Dramatic Competition at the 1986 Sundance Film Festival) for its unapologetically frank treatment of gay male desire and devotion in the wake of a plague.

Nearly 40 years later, Parting Glances remains uncommonly wise and nuanced about death, domesticity, and companionship, its drama rooted in a particular time, place, and community, one opting for ebullience in the face of catastrophe. Michael and his pals make an after-hours detour to the defunct gothic disco Limelight while the rapturous sounds of the trailblazing U.K. synth-pop outfit Bronski Beat dominate the soundtrack. This world has all but ceased to exist, but Parting Glances preserves it forever as a snapshot, one made indelible, in part, by the vivacity of its best-known (and perhaps least expected) ensemble member: Steve Buscemi.

As Michael’s ex-lover Nick — a new wave musician dying of AIDS — Buscemi is a dynamic presence, putting his soon-to-be-signature stamp on a character for which, on paper, he was all wrong. Sherwood had originally envisioned Nick as tall, strapping, and middle America handsome, but as he sat in the audience of a two-man improv comedy show in 1985, his attention was seized by a slender, squirrelly performer with a Brooklyn accent and an entrancing pair of blue-green eyes.

When he was invited to read for Parting Glances, Buscemi was a former firefighter who had little professional experience but years of training at the Lee Strasberg Institute under his belt. The actor doubted his suitability for the project and subsequently blew his audition, but Sherwood had already made up his mind: the role was Buscemi’s if he wanted it. When asked about his decision to take the role decades before straight actors-playing-gay became a divisive norm, Buscemi told the LGBT newsmagazine In the Life, “I think any actor who would have turned down playing that part because the character is gay would have been insane.”

Nick spends much of the film relegated to an apartment that has become a cocoon for life’s final transformation. He subsists on Michael’s care and succor, biding his dwindling time listening to opera and hip-hop, watching himself on MTV, recording his will, and communing with an apparition of an already departed friend. He is starved for the attention and connection of which the disease has deprived him, but he is also, indisputably, a force of nature beaten into atypical repose.

It is impossible to overemphasize the power of Buscemi’s gaze, one of the most piercing and expressive in all of movies and television. However what’s so striking about his work in Parting Glances is the vibrancy of his unpredictable cadences and the roundedness of his restless physicality. Buscemi arrives on screen a fully-formed human being. One can easily imagine what Sherwood admired when he first discovered the actor: undeniable talent, certainly, but also an innate ability to carry a character in body and voice — sometimes casually, sometimes eccentrically, but always compellingly. He seems, even at this nascent stage of his career, to withhold nothing in the construction of a character.

Behind the scenes, Sherwood aspired to keep Buscemi in a state of near-perpetual agitation befitting his idea of the character. The pair could clash, especially when the director would pore over the script with the actor, studying it line by line and dictating his preferred readings, only to then reprimand Buscemi for not being spontaneous enough once the cameras rolled. (“Whatever he was doing he was doing it right,” Buscemi told LA Weekly in 2007, “because the role remains one of my favorite performances.”) The Bensonhurst-bred Nick has the air of the streetwise smart-aleck and the actor excels with some of the script’s drollest bon mots, as when Buscemi tells an overeager twink, “We had more fun in one weekend than the entire state of New Jersey’s had since the signing of the Declaration of Independence.”

But Buscemi gives the character dimensions that exist outside the written word, his presence signaling a world of play and conviviality lately eclipsed by unfathomable tragedy. This is not an impersonation of gayness beholden to the stereotypes most prevalent and legible in pop culture at the point of production, but an inside-out incarnation of a specific gay man, rooted in mordant humor, ardent affection, and lust for life. Nick can be brash and petty, arch and pugnacious, but he also radiates an effortless cool that derives from his very idiosyncrasy, his fluid embodiment of the impish and the angelic. The tender ease with which Buscemi leans on and locks his arms around Ganoung suggests an intimacy borne of years of inseparability, a love thick with history and without limit. And when Sherwood has the actor pose against a sunset in a black leather jacket, running a hand through his sweptback hair, Buscemi becomes what too few filmmakers have seen him as: a vision.

Buscemi’s performance made an unexpected fan out of Quentin Tarantino, who would go on to cast the actor as Mr. Pink in his 1992 debut (and Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize winner) Reservoir Dogs. “The memory of this too-cool-for-school New York underground rodent, sitting on his lover’s lap […] has stayed in my heart to this day,” Tarantino wrote in BOMB Magazine in 1993. For Tarantino, Buscemi’s acting was “so real” that the director assumed he was the kind of nonprofessional performer that one encounters in underground films of the era and never encounters again. On the day that Parting Glances was released, Buscemi received a call from an agent at ICM and the actor has seldom been absent from our screens since. Sherwood’s film runs the risk of being diminished in the scope of Buscemi’s extensive filmography, which has enshrined him as a king among character actors and the skillful writer-director of such Sundance Festival selections as Animal Factory (2000), Lonesome Jim (2005), and Interview (2007).

For Buscemi, it all begins with Parting Glances. His character is a totem whose heart still beats and whose blood still boils. As the film’s sole embodiment of life lived with AIDS, Buscemi’s Nick bears the radical promise that the infected, the suffering, and the dying will not go quietly. This promise is stated verbally, but it manifests most profoundly here in his spirit of defiant irrepressibility and a face impossible to forget.