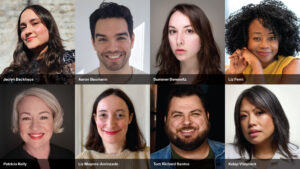

From left, Luella Brien, Matthew Galkin, Razelle Benally, Mary Kathryn Nagle, and Lucy Simpson attend the 2023 Sundance Film Festival “Murder In Big Horn” premiere at the Egyptian Theatre on January 22 in Park City, Utah. (Photo by Steven Simione/Getty Images)

By Vanessa Zimmer

There’s an epidemic on Native American ground, and residents on the Northern Cheyenne and the Crow reservations in Big Horn County, Montana, don’t think it’s hypothermia.

The body of Henny Young, 14, was found in fairly open country within 200 yards of the house where she was last seen in Lame Deer, about three weeks earlier. The official cause of death? Hypothermia. But the body was untouched by coyotes and other predators, surprising given the length of time she would have been exposed. Her parents thought her nose looked broken, and they observed bruises and scratches. And she wasn’t wearing her own clothes, mother Paula Castro says: “I know something happened to her out there.”

Henny Scott’s case is just one story told in Murder in Big Horn, a three-episode documentary about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women that premiered January 22 at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival. Directors Razelle Benally (Oglala Lakota/Diné) and Matthew Galkin present a multilayered exploration of the country, culture, and local law enforcement.

“The sheriff’s office clearly was stonewalling [the families of victims],” Galkin says in the Q&A following the film. “And they ultimately stonewalled us. So we felt like there was a story to tell.”

Natives say their missing-person reports are ignored, and that cases are sometimes lost in the gap between jurisdictions of local authorities and federal agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the FBI.

At the Q&A, journalist Luella Brien calls for better representation of Natives in federal agencies and other government bodies, to look out for the welfare of the tribal population. Indigenous people are “invisible” in our country, says Lucy Simpson, executive director of the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. “We’re seen as people who existed in the past.”

“So much of our reality in Indian country is in the hands of the federal government,” adds Simpson. “There are actually few in our federal government who actually know what’s going on.”

Busy Interstate 90 plausibly offers opportunities for a quick grab and exit from Big Horn County for sex traffickers and drug cartels. Threats can also come from within the tribes themselves, according to the documentary, given that Native culture has been damaged by a reservation system that created dysfunctional individuals and dysfunctional families.

In one episode, Brien, editor of the Big Horn County News, remembers when her father’s sister went missing in 1977. “It feels like we’re born to it,” she says sadly.

Still, she continues investigating and reporting, even though officials consider the cases closed. She won’t give up pushing for answers, from outside and within: “I think my community deserves to know.”