Barbara Kopple’s Oscar-winning documentary “Harlan County, USA,” edited by Nancy Baker and Mary Lampson.

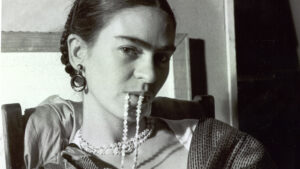

Mary Lampson

At the Sundance Film Festival last month, editor Mary Lampson presented a keynote highlighting the role of an editor and her journey through the ranks of the industry during Sundance Institute and the Karen Schmeer Film Editing Fellowship’s Art of Editing Reception. Below we’ve published Lampson’s speech in full.

First I’d like to thank Sundance Institute and the Karen Schmeer Film Editing Fellowship for asking me to speak today, and also Adobe for supporting this event.

So recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about editing. It’s something that formed in my twenties, something I returned to in my fifties and something I can’t stop doing in my seventies. I’ve worked on a lot of films but the truth is—and I think this is true for all of us—with each new job, even after all these years, I always start in the same place: Looking at a blank screen. And that moment is even scarier than standing up here today.

Kristin Feeley (Labs and Artist Support Director) knows I’ve been putting some of these thoughts down on paper and she asked me if I’d consider sharing some of it with you. At first I said no—I hate public speaking. But after thinking about it a bit more, I said yes because I was pretty sure I’d learn something by standing here and telling you “my story.” I guess I hope talking about some of the things I’ve learned along the way might help some of you in some small way as you think about how you do your work and why. So here goes… Starting in 1963. College.

I studied Russian for my first three years of college. Why? Because I loved languages and the Cyrillic alphabet was mysterious and cool. Without even knowing it, I was following in the footsteps of my foreign service parents and thank god, my Junior year, back from a semester in the Soviet Union, I realized the path I was on was leading me to a place I did not want to go: translator, academic, foreign service officer. So in my senior year I started taking theater and film classes. Why? Because that’s what some my friends were doing, and that’s how I discovered 16mm film.

I was very shy so directing was hard. But when a reel of developed film came back from the lab and there was an image frozen into the emulsion of each frame, that image reached out to me and I could see relationships between the shots. I liked the control and power of deciding where to make each cut. I also liked the tools themselves. The grease pencils which marked the cuts you made. The soothing monotony of rewinding the film on a set of rewinds. The bins that held the shots you chose. Even the “velvet” which cleaned the dirt from the cutting room floor. It was so deceptively simple. It was all so physical. I loved it all.

So in 1967, I moved to New York to look for a job as an apprentice editor. Using the yellow pages as my GPS, I pounded the mid-town pavements of Manhattan’s “film district” day after day, knocking on doors, for two-and-a-half months, one rejection after another. Finally, I knocked on the door of a commercial house, immediately after they had fired the “print break down girl” and they hired me on the spot. As I went downstairs to the cellar where the cutting rooms were, I heard a sexy voice saying: “Take it off, take it off, take it all off,” over and over and over again. It was the iconic Noxzema commercial, directed by Bert Stern, one of the original “mad men” of the 1960’s New York advertising world. The editors—who quickly became my teachers—were generous, funny, a little snide, and very smart. I learned a lot and I learned it fast. Two months later I was laid off, which was awesome because I would have been too scared to quit.

I knew just enough to pass myself off as an assistant editor, which landed me a job at Leacock-Pennebaker. My second job. I got that interview through a connection: I was teaching filmmaking to kids at night after work and one of the dads knew Ricky (Richard Leacock) and Penne (D.A. Pennebaker) from the early days at Drew Associates. This time I lied and said I knew a lot more that I actually did. But, a year-and-a-half later, when I met Emile de Antonio…my third job. I didn’t lie, so he knew I had never edited anything by myself when he hired me. I had just turned 23. I think he saw my inexperience as an asset. He liked working with young people because they were still free of all of the rules, the formulas, the baggage that often accumulates with experience, and then God forbid, success

D, as he liked to be called, was a political filmmaker. Point of Order, his first film, made when he was 45, is about the downfall of Senator Joseph McCarthy and is constructed entirely from the kinescopes of the Army McCarthy hearings. It had a long theatrical run, which surprised everyone at the time.

D was my mentor. He loved Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Buñuel, Kurosawa, and the Marx Brothers. And he hated everybody else’s movies; he criticized them all, even though he never saw any of them. He was an impossible guy and he taught me a lot. He derided the “perfection” of Hollywood films, the “balance” of television… He loved rough edges. He gave me the confidence to mess around—to experiment—and as I learned to play with footage on the first pass of a scene, I began to edit for real. With my heart in my throat, I’d ask him to take a look what I’d cut, and he could always see beyond the mess I had made and say, “Oh, that’s interesting, now maybe we could do this.” We had a tremendous collaboration and I began to find my “voice,” my style.

We went to the archives together and found extraordinary stuff. National Guard tanks and armed policemen invading African-American neighborhoods in Miami during the 1968 Republican Convention for our film Millhouse, A White Comedy, a pre-Watergate film about Nixon. I’m sure an archivist would have found many of the things we found, but would they have pulled the tiny moments? The head turn? The child’s face in the policeman’s arms looking straight into the camera? Maybe yes, maybe no, but I still would not want to have missed the moment of finding those shots. These newsreel out-takes were our rushes. That’s when I came to hate the term “B-roll” because I had learned by then that films are constructed in the spaces between the images and the words. When the images are demoted to “B” they become illustration, nothing more, and I don’t think you can make real meaning, emotional meaning, with words alone. If you go that route you are left with nothing but text; the subtext never rises to the surface. You show what’s happening, but you don’t reveal what’s really happening. And the audience will be locked out. So that’s how I started, but what shaped me?

Who am I? I’m the child, as I’ve said, of foreign service parents. I have no American roots. I’ve always had other people’s stories rubbing up against my skin—in Turkey, Germany, Washington, D.C., and London. At age four, I watched through a basement window a baby being born in Turkey, until someone noticed me and shooed me away. I picked apples from a tree in the courtyard outside our apartment building, until the angry owner stormed out, pulled me down, and slapped me hard. My mother came out in a rage and marched the man down to the police station, making him walk in front of the car as she drove. I’m pretty sure I got lost in the shuffle, the high drama, and so I became a watcher… always a little bit detached.

In some ways I think the films we make are like the foreign service life I lived. Each time you move, or start a new film, you enter a different world. Everything is strange. The smells are different, the sky is different. Everything is new and you don’t understand the way things work because all the rules are different, too. Then little by little, because you have no other choice, you start to make sense of the chaos. You understand something and you’re exhilarated; and then you realize you understand nothing and you’re depressed. This cycle of despair and exhilaration happens time and again as you begin bringing things together until finally you find connections and uncover the logic of the place. And then you move on. You pack up your stuff, get on a boat, and you’re off again to a new place which will be home for the next four years. Then four years later you move again.

So why do I keep doing it? Because each film is different. Because it makes me think and it keeps me young. Because it’s really hard and asks a lot of my brain, my heart, and my hips. I don’t always succeed. I’ve gotten fired or quit more than once—incredibly painful in so many ways. But even in the films I don’t finish, I leave a part of myself somewhere in the film (although sometimes it’s hard for me to find). I believe in laughter… the absurd… the incongruous. [I believe] in complexity. And I love ambiguity. I also love wasting time… daydreaming… noodling. My favorite post-it is the one I wrote that says ‘FUCK exposition’—the place I think you should never start. I‘m suspicious of perfection when it comes too fast and I’m also suspicious of happy endings.

When we sit in that chair, we have extraordinary power and a great responsibility. We are “playing” with someone else ‘s life and we need to be careful. We owe it to the people whose stories we tell. Much has changed as we have moved from this…

To this….

The old analogue world was not better. It was inefficient, expensive, and inaccessible. Drudgery in so many ways. But the films were just as good.

Finally—here’s my multiple ending—I want to end with something Agnès Varda said a few years ago:

“I don’t believe in inspiration that arrives like a bolt from the blue—if it doesn’t also arise from your body and your immediate lived experience. That’s why I always refer to ‘subjective documentary.’ It seems to me that the more motivated I am by what I film, the more objectively I film.”

And, of course, the more objectively we edit.

Thanks.