[Pictured: The Doom Generation]

By Stephanie Ornelas

“Independent films have emerged as not only a unique art form, but as a significant means of chronicling our times. Preservation will ensure that this art form both endures and becomes an ongoing resource.” – Robert Redford

The preservation risks posed to independent cinema are dire. Supporters of the craft might not be aware that many beloved indie films are at risk of being lost and forgotten. Motion pictures of all types are deteriorating faster than archivists can preserve them, partially due to film lab shut downs, and independent projects are in jeopardy the most. But programs and organizations like the UCLA Film & Television Archive and Sundance Institute have worked to change that.

Preservation Week — a time to mark the importance of preserving historically significant materials — is observed during the last week of April, so there’s no better time to revisit how Sundance Institute and UCLA came together in 1997 to form the Sundance Institute Collection at UCLA in an effort to address the preservation risks facing the independent film industry. The collection works to track down films and reconnect with the artists, secure enough funding for the restoration projects, and coordinate with digitization/restoration vendors who then work on the actual film’s preservation. A copy of each project’s digital archive and a DCP (Digital Cinema Package) is then moved to UCLA’s archive, where they live forever.

Preservation Week — a time to mark the importance of preserving historically significant materials — is observed during the last week of April, so there’s no better time to revisit how Sundance Institute and UCLA came together in 1997 to form the Sundance Institute Collection at UCLA in an effort to address the preservation risks facing the independent film industry. The collection works to track down films and reconnect with the artists, secure enough funding for the restoration projects, and coordinate with digitization/restoration vendors who then work on the actual film’s preservation. A copy of each project’s digital archive and a DCP (Digital Cinema Package) is then moved to UCLA’s archive, where they live forever.

The collection has amassed 2,300 restored Sundance-supported titles and brought archival screenings back into focus for Sundance Film Festival audiences to rediscover. Gregg Araki’s The Doom Generation and Marc Levin’s SLAM joined that list when they screened in the 2023 Sundance Film Festival’s From the Collection section.

One remarkable outcome of the Sundance Institute–UCLA partnership is that it has not only brought these films to new audiences, it’s allowed viewers beyond the Festival to see this powerful work, since oftentimes projects that go through the collection are restored as part of a subsequent re-release. After its anniversary screening in Utah, The Doom Generation was re-released in select theaters in April and is still screening across the U.S.

“These films have not been available legally for years, which is why it’s so shocking that there’s still an audience for them, because they’ve just sort of lived on YouTube or some weird website,” says Araki during a Zoom interview. “But there are so many films from the ’90s that aren’t retrievable because they are lost.”

The Doom Generation meets a new audience

When the uncensored director’s cut of The Doom Generation screened at the 2023 Festival in its remastered state, Araki was stunned that the majority of audience members were younger viewers who had never seen his film on the big screen — but that didn’t mean they hadn’t seen his film at all. Many of them had watched pirated versions of The Doom Generation, so Araki was thrilled to be able to show this restored version to 2023 audiences.

“I remember it was like 80% new [viewers] and I was a little bit shocked,” says Araki. “It’s crazy to me that this movie we made 28 years ago has such an intense following.”

Marcus Hu, co-founder of Strand Releasing — who is spearheading the film’s preservation — was also surprised with the turnout of a younger audience as well as their reaction to meeting the film team.

“I thought there was going to be a fan base, I didn’t know just exactly how intense it was going to be,” explains Hu in a Zoom interview. “I saw basically teenagers who were meeting Gregg. These kids had become so connected to that movie, they were almost about to start crying.”

Chimes in Araki, “When you’re looking at some sort of pirated copy, you’re looking kind of through a window at a world. But seeing it on the big screen with an audience, it immerses you in the world, you’re a part of it, and it takes you away to this place. When you’re watching it on a laptop, you don’t have the same visceral experience of it. And that’s why I’m so excited. We’re screening in more theaters now than the movie did in 1995.”

A full-circle moment for SLAM

Like The Doom Generation, SLAM resonated strongly with 2023 Festival viewers.

“One of the things that was really moving is that somebody after the screening came up to me and said, ‘I was here at the premiere in 1998, and I think the film plays better now than it did 25 years ago,’” director Marc Levin says in a Zoom interview.

“Obviously with everything that’s happened in our country and certainly after George Floyd and all the massive demonstrations, the consciousness and the issues are more front and center. Although they were pretty front and center for us back then.”

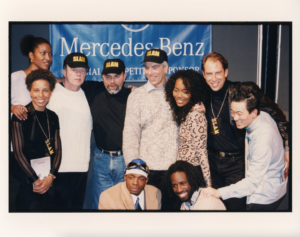

Levin was thrilled when John Nein, Senior Programmer and Director of Strategic Initiatives at Sundance Institute, reached out to tell him about the Institute’s partnership with UCLA Film & Television Archive and how SLAM could play a role in the 2023 collection. The opportunity with the Sundance Institute Collection at UCLA allowed Levin to reunite many of the cast and crew who hadn’t seen each other in over two decades, and he shared the inspiration behind SLAM with new audiences.

“I was aware that we were approaching our 25th anniversary, but I hadn’t really given it much thought to what could happen, so the call from John Nein was incredibly fortuitous.”

It was important to Levin to bring the SLAM family together for this momentous screening. He brought as much of the team as possible to Utah — including special guest Momolu Stewart, the freestyling inmate who makes an appearance from his prison cell next to protagonist Saul Williams in the film. During the time of filming, Stewart was a 16-year-old serving a life sentence. But he showed up to the Festival a free man. It was a powerful moment for audience members to witness.

“He was the icing on the cake for the whole weekend,” says Levin of Stewart. “To see someone who went through what he went through for 22 years inside the belly of the beast who somehow discovered his own humanity, his own creative abilities, his own vision, his own commitment to helping other young people not repeat the mistakes he made, it was just really powerful. It moved us all.”

And as for the updated version of SLAM, which was digitally restored from the 35mm interpositive, it’s safe to say that Levin was pleased with what he saw.

“[The restoration team] did a great job in terms of cleaning it up and making it more vivid, more alive — the color, the richness, it just popped,” Levin explains. “I went through it with them for a final round and it was great.”

The search for film elements: a cautionary tale

Citing his own journey with The Doom Generation as a prime example, Hu strongly encourages filmmakers to prioritize knowing where their negative materials are. And if they don’t know, there are ways to try to track them down.

“Independent filmmakers need to be aware of where all their elements are,” stresses Hu. “Have those producers been keeping track of things like the IP (interpositive) and IN (internegative)?” Hu asks, referring to master materials for creating HD transfers for today’s standard.

Araki explains how easy it is for these important films — many of which artists spend years creating — to be lost forever.

“These [film] labs are out of business now because of digital technology,” says Araki. “So they’re just throwing negatives away, they’re throwing IPs away, and [the filmmakers] don’t even know about it. This footage that’s so precious and a huge, important part of film history is literally just going into a dumpster. We were lucky, but there’s a lot of people who aren’t going to be so lucky.”

“The lab had shut down and disposed of the negative materials. When you think about the sheer volume of film out there, someone’s paying for the facility, the storage fees, and it’s really expensive because it’s got to be temperature-controlled otherwise it gets vinegar syndrome, so they just start destroying them.”

And The Doom Generation could have been totally destroyed within the year too, according to Hu. The search for the film’s elements began when Nein reached out about wanting to restore it as part of the 2023 Sundance Film Festival’s From the Collection section. And its recovery was no easy feat, as they had to search multiple locations for their materials.

When Hu and Araki were unable to recover all that they were looking for — they had the IN, but not the IP — they drafted Todd Wiener, Motion Picture Curator at UCLA Film & Television Archive, to do a deep dive for their materials. Wiener contacted the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and as many film labs as he possibly could. Finally, one lab technician at Technicolor responded saying the lab had what Hu and Araki were looking for. But there were more challenges to come.

“Apparently, someone did some printing of that IP and Trimark [Pictures] had no idea. They were the last owners of the film. So we went through the process of trying to prove who we were as owners,” explains Araki.

Despite the challenges attached to an evolving industry of acquisitions and new technology, Araki and Hu received access to all the film elements they needed and eventually moved everything over to the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences, where Araki has an agreement to house his entire library.

“I’m a better filmmaker now than I was 28 years ago,” Araki laughs. “To bring all of that to the new copy and make The Doom Generation new again is something that I’ve been dying to do for years. I’m just so grateful and so moved by the idea that there’s such a passion for [the film] and such love and support for it.”

But, as Araki warns, not all filmmakers have been fortunate enough to recuperate the necessary elements of their projects. Such was the case for Levin, who, to this day, is still unable to locate the original negative for SLAM.

“We never found the super 16,” says Levin. “But we did find the 35mm interpositive, which other prints were made from. Lionsgate was, thankfully, very cooperative and helpful.”

It’s a grim thought to consider that the industry is in danger of losing many of the films that defined crucial movements in independent cinema, but if filmmakers are able to heed the lessons learned by Araki, Levin, and other artists before them, they can minimize the risk of losing something so invaluable. And with the help of initiatives like the Sundance Institute Collection at UCLA, more lost films can be found and protected.

“We often are very focused on discovery and new artists and new work, but at the same time, the reason why we are who we are is because of this history,” says Tanya De Angelis, Associate Director, Archives & Collection for Sundance Institute.

“Some of these artists didn’t get the attention that they deserved at the time for a variety of reasons. There’s so much dialogue that can happen and conversations that need to happen by resurfacing and bringing this work to light.”