Chelsea Christensen (right) greets a Festival volunteer at the Park City building that houses official merchandise for the Sundance Film Festival. (Photo by Jutharat Pinyodoonyachet)

By Vanessa Zimmer

Where do you start to tell the story of 40 years of poster art at the Sundance Film Festival? At the beginning, some would say. No, I would reply, you start with the people.

Maybe you’d start with Chelsea Christensen, because, if you’re looking for a cheerleader for the independent film festival (and its parent Sundance Institute), she’s the one. You’ll likely find her in an unassuming warehouse in Park City, Utah, that houses the official merchandise for the Festival.

At the height of the Festival season, Christensen will be cheerfully packaging and sending out orders for coffee cups, hoodies, T-shirts, water bottles, beanies, puffer jackets, socks, everything — including posters.

Each year, the poster becomes a symbol of the January Festival. “Some people buy it for the year, as a souvenir, and some people buy it as a beautiful piece of art,” Christensen says in a Zoom interview. “And if we can combine the two together, where people love it as a souvenir and as a piece of art, I think that makes a perfect poster.”

Now a veteran of her “26th Festival” — funny thing, Sundance Institute staff tend to measure their employment by the number of Festivals rather than years — Christensen identifies some favorite designs over the years.

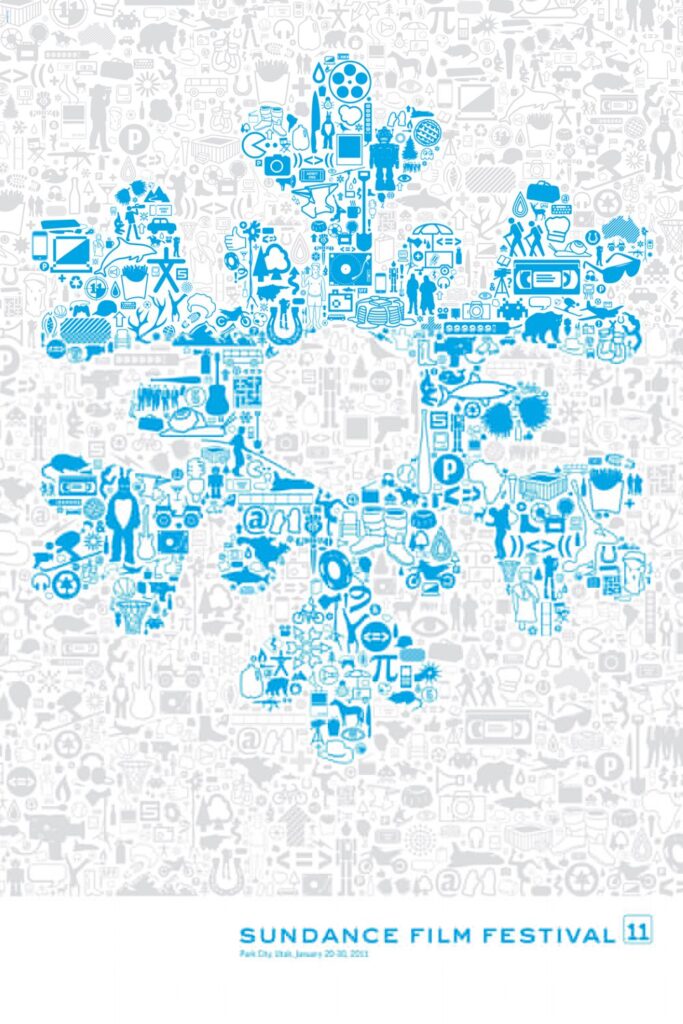

Her all-time favorite is the 2011 snowflake poster. At first glance, it’s a blue snowflake on a grayish background. Look closer, and the blues and even the grays turn into specific figures — all representing films that have come through the Festival over the years. There, at the left, the man in the rabbit suit, that’s from Donnie Darko. Above his head, a rat from Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop.

“It was interactive,” Christensen enthuses. “It was a game, it was fun, and it has a snowflake — it basically represents Utah. And I never get tired of looking at the icons and picking out the movies that each one represents.” It’s pure, never-ending entertainment, just hanging on the wall.

And it’s a true collectible: The poster sold out that year and has never been offered again.

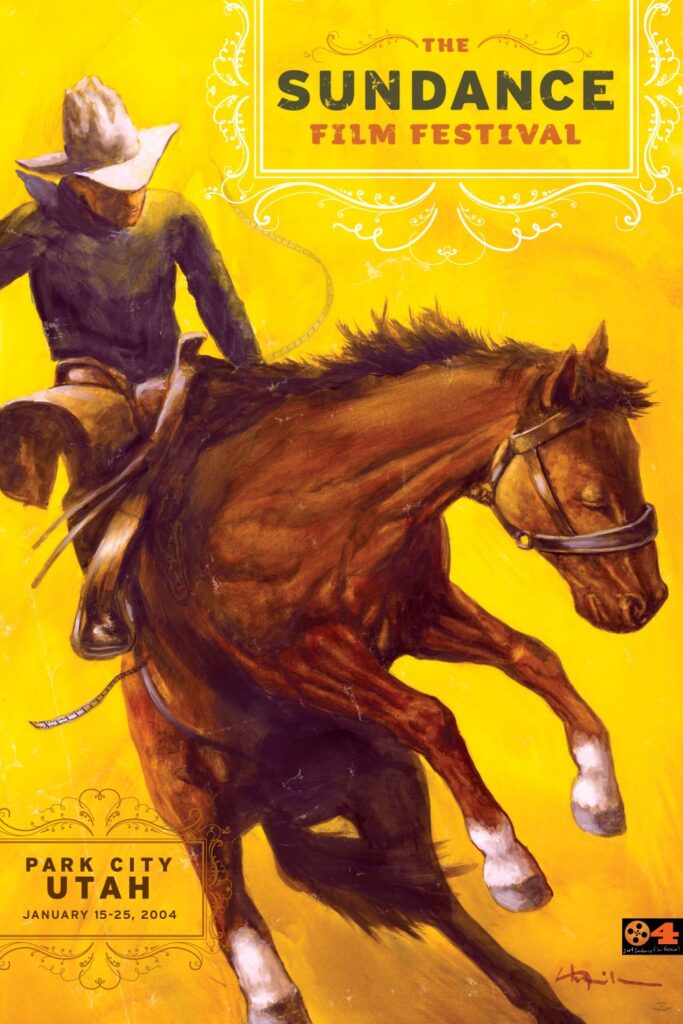

The same is true of the 2004 Limited Edition poster — many years, the Institute produces a Limited Edition version in addition to the regular poster. Christensen calls it “the cowboy poster,” and it’s another of her favorites. It features a cowboy with a white hat and flapping chaps on a bucking bronc.

“It’s just a giant cowboy,” Christensen says. “It’s like we are in the Wild West. We are in a mining town [Park City became a booming silver mining town in the 1870s]. [Festival founder] Robert Redford wears his cowboy boots every day. … Even in his 80s, he’s still wearing those cowboy boots every day.”

To her way of thinking, the Sundance brand is tantamount to “the Wild West of filmmaking.”

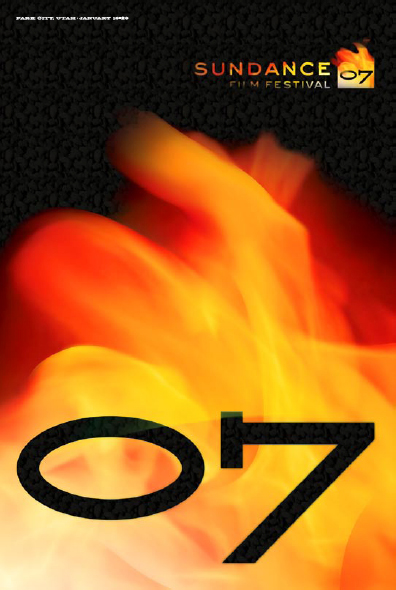

Probably third on Christensen’s list of favorites are the regular and Limited Edition 2007 posters — “the year of the fire.” Not as in a destructive fire, but a flame that symbolizes the spark of creativity.

Christensen was running the Festival Headquarters that year in a Park City hotel. Inspired by the posters, she asked hotel maintenance to help her change out the light bulbs in the ballrooms and replace them with the bulbs that resembled flickering flames. “I was just so into the theme of sparking the flames.”

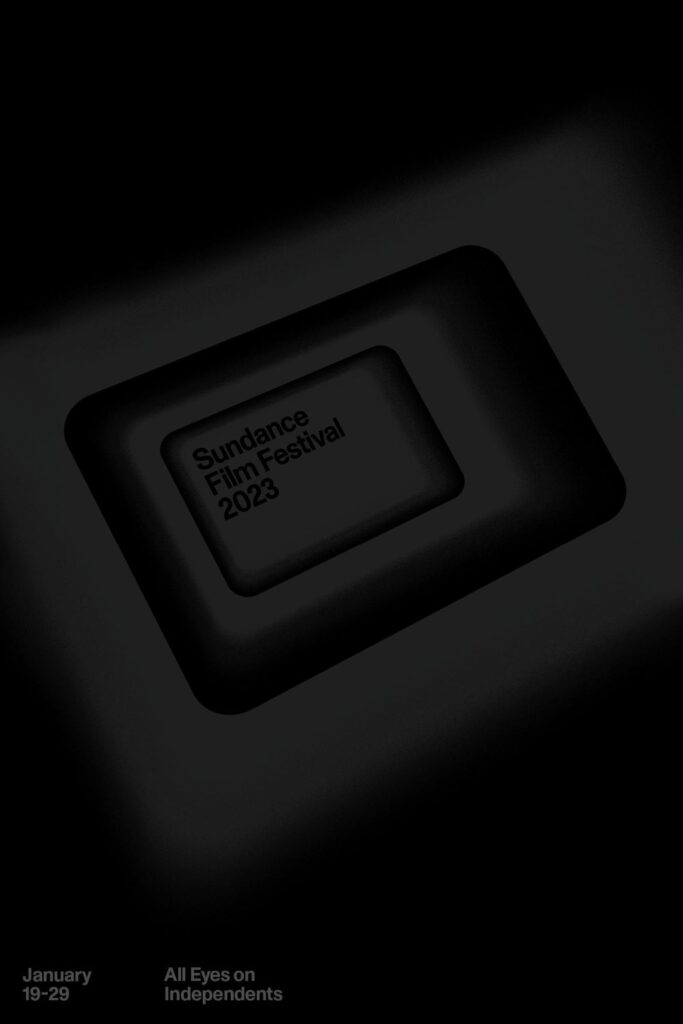

Christensen and Sundance Institute graphic designer Sonja Anderson (“This was my sixth Festival”) both worked with a Utah printer to capture an effective ink rendering of the unique PORTO ROCHA–designed poster for the 2023 Limited Edition version. Sundance types refer to it as a “tunnel” design, pulling the eye inward.

“It draws you in, it totally does, because it’s very subtle,” Anderson says in a Zoom interview, calling it one of her favorite posters. “I like things when they’re a little bit intriguing versus in your face.”

Anderson also admires the 2020 Limited Edition poster, likewise among the more subdued, colorwise, of the Festival posters. “I’m a minimalist, I guess,” she shrugs.

Studio Lowrie, a two-man company operating out of a shipping container in London, designed the 2020 poster. The concept arose from the idea of light beams coming out of a projector, as well as the reaction of the human eye to light, according to an article in It’s Nice That magazine.

The Limited Edition, with its subtle and basic colors, was Anderson’s favored version. The regular 2020 poster has a deep orange background. Studio Lowrie also paired its simple geometric shapes and centers with bright, rich backgrounds of green, yellow, and purple for banners and signs that stood out against the snowy January landscape of Park City.

Perhaps like-minded on the minimalist scale is longtime Sundance Institute archivist Tanya De Angelis (“2005 was my first Festival”).

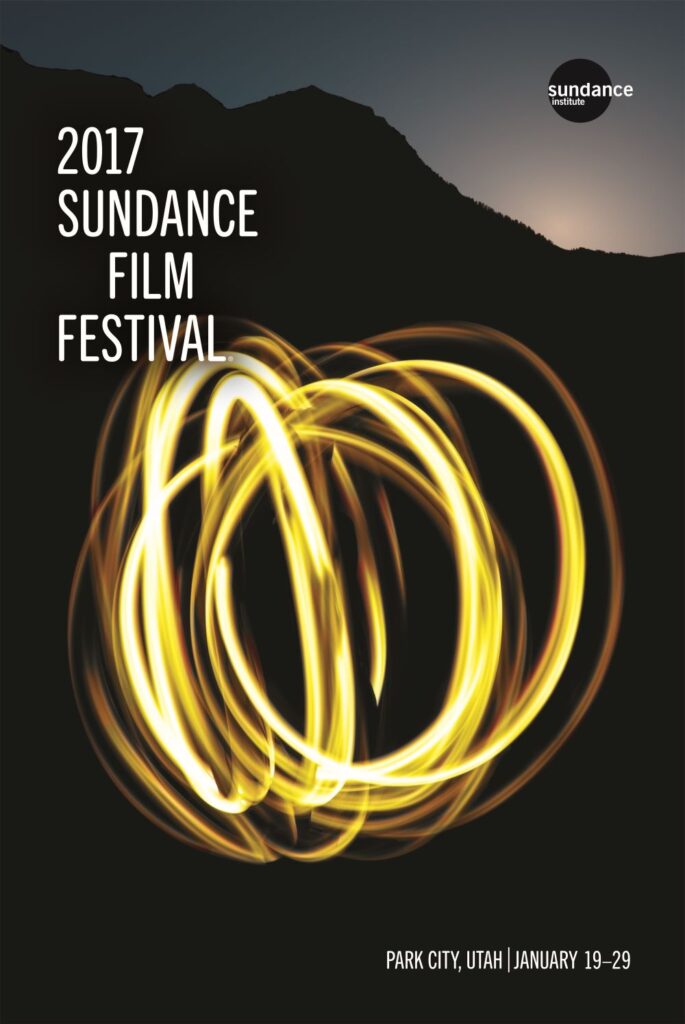

Consider the 2017 poster, which involved the Institute content team accompanying photographer Jonathan Hickerson to the Sundance Resort, where they proceeded to play with flashlights and the camera shutter.

“I think I enjoy that one a lot because it’s one of the only ones in the last 10–15 years that was actually a photograph and people were technically in the photo, you can’t see them, but it’s something that was created in real time.” An extra boost is the mountain skyline in the background.

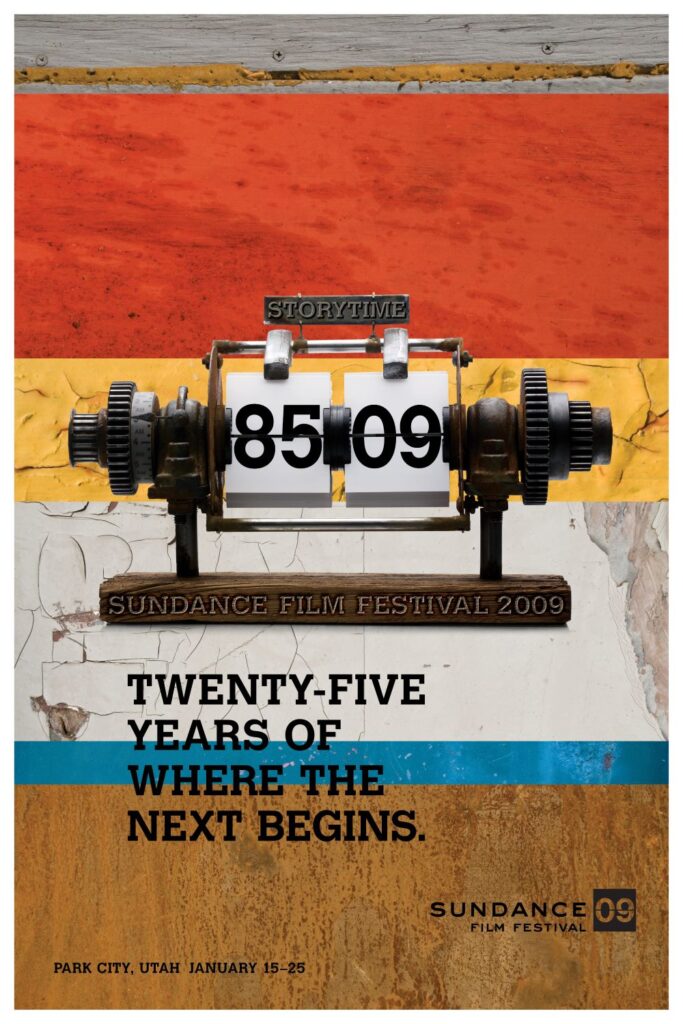

The steampunk clock of the 2009 poster also appeals to De Angelis, in part because she remembers the clock was re-created in three-dimensional form for the awards statuettes passed out that year.

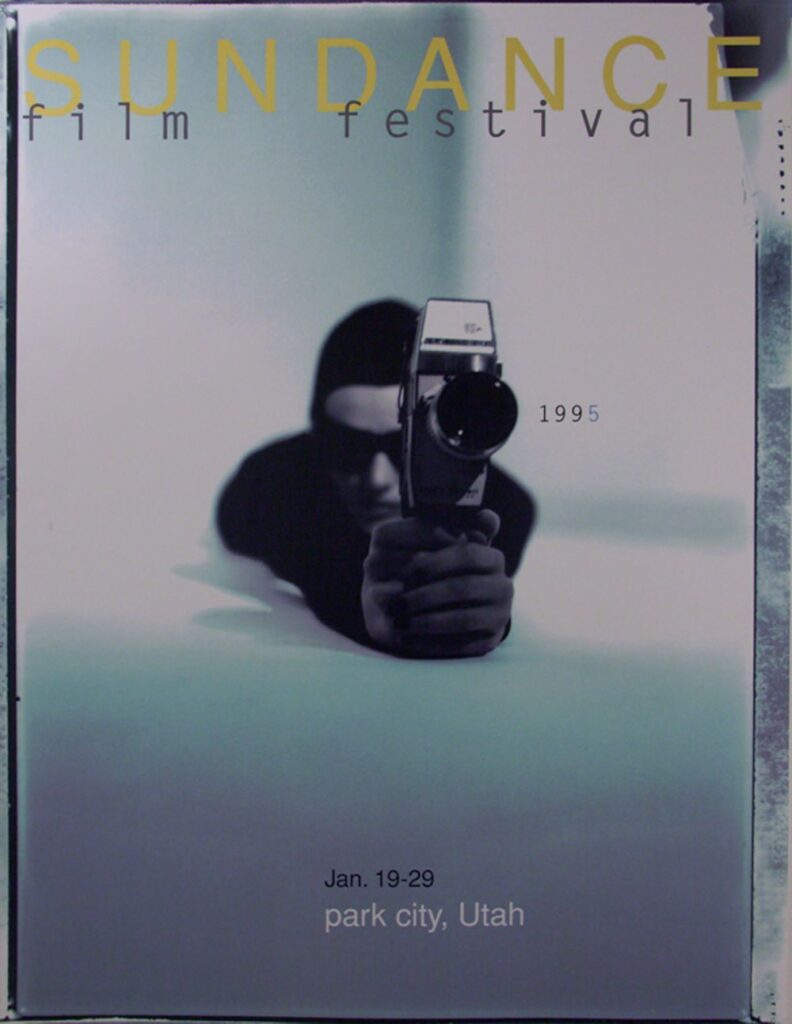

Two other De Angelis selections also use human figures: 1) the 1995 poster of a person lying stomach-down, pointing what appears to be an 8mm movie camera at the camera that actually recorded the shot, and 2) the 1987 poster of a man “who looks a little like David Lynch… and there’s a film reel kind of circling around his head.”

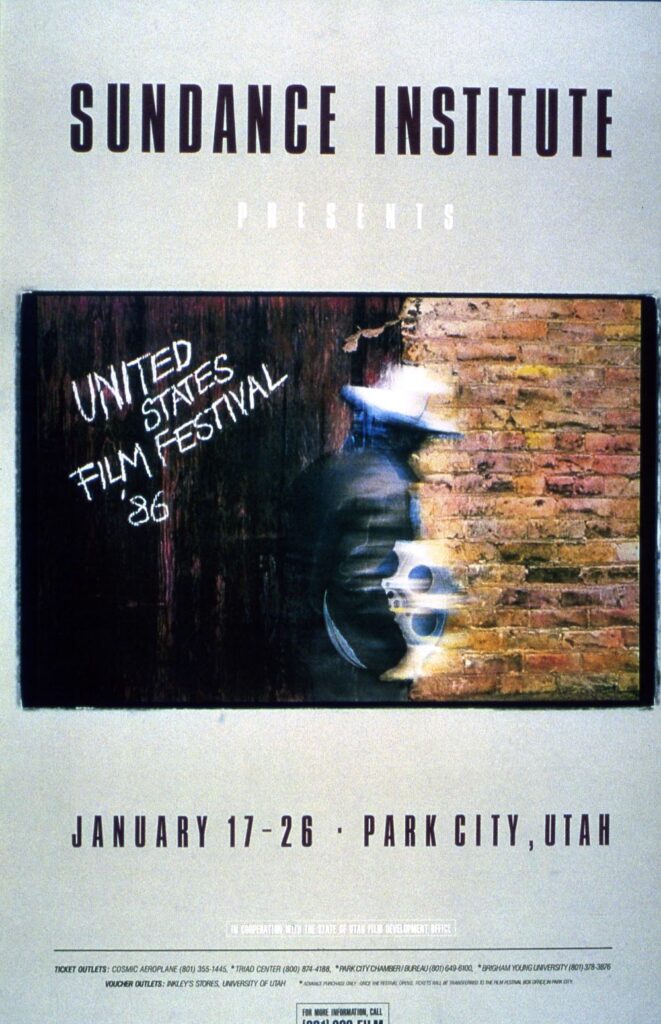

“It’s very like: This is a film festival. But also just kind of fun and very, very ’80s-feeling,” De Angelis says of the latter. That’s fitting, because back then the Sundance Institute was just getting its start.

Redford established the Institute in 1981 with the intention of nurturing emerging storytellers with new and distinctive voices, apart from the rigid Hollywood studio system. Redford and the Institute assumed control of the Park City-headquartered U.S. Film Festival in 1985, and by 1991, it was called the Sundance Film Festival.

Gilberto Schaefer was a new Salt Lake City businessman back then, not too long after arriving from his native Switzerland. He and a partner were trying to get their graphic design business off the ground, and some branding work they did for the Deer Valley ski resort apparently caught the eye of Redford’s group.

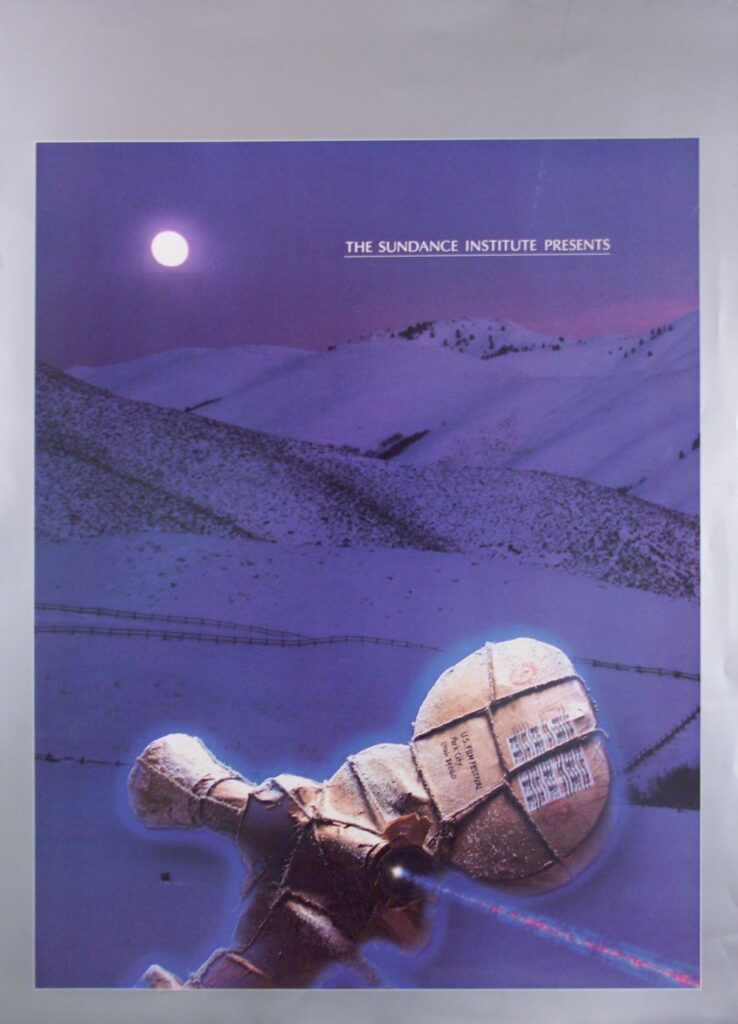

As a result, Schaefer’s company, Innovation, designed the 1985 and 1986 posters, under the U.S. Film Festival moniker.

Schaefer recalls how he and his wife wrapped up a borrowed movie camera in their kitchen, much like the artist Christo did with his art, for part of the 1985 image. Schaefer and his partner then came up with the blue/lavender mountain for the background. The concept was to convey the idea: Something is coming.

Redford was looking for something more abstract after that, and Schaefer’s vision of hiding a movie camera in each year’s poster didn’t fit the bill. Schaefer was disappointed, but he maintains a heart full of respect for Redford and his mission for independent film.

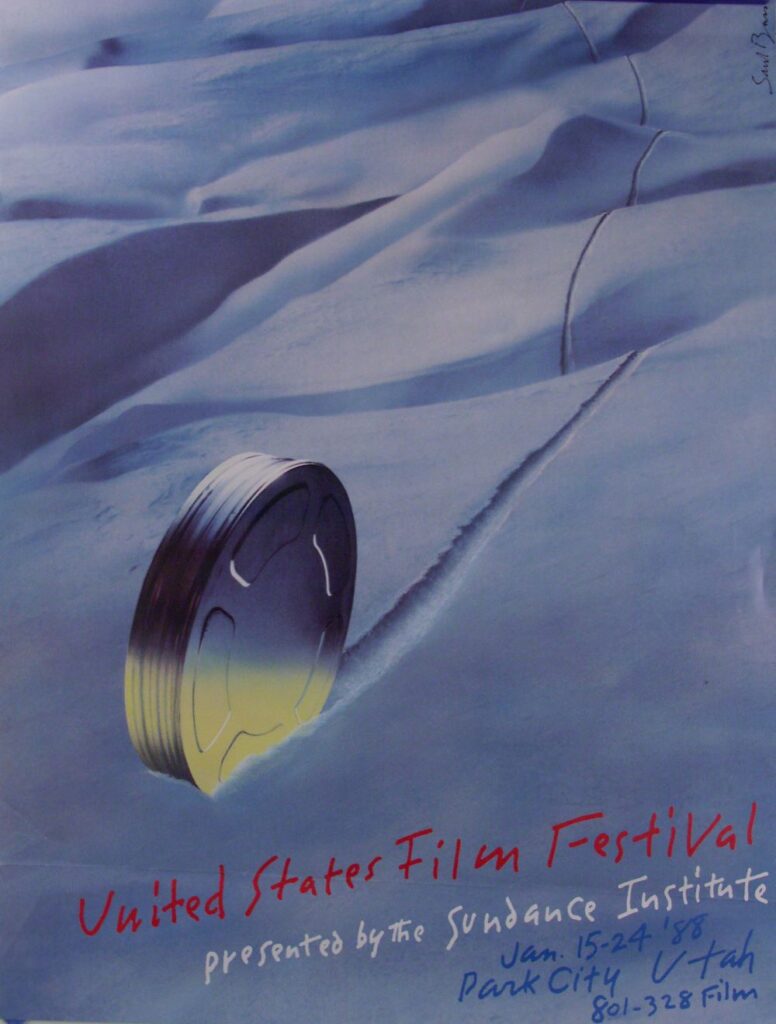

The 1988 poster was designed by the legendary Saul Bass — take note of his signature at the top right corner. Bass designed iconic logos for corporations like United Airlines, AT&T, and Hanna-Barbera, but was probably best known for movie-title treatments, like the cutout of the arm of a drug addict with the title and opening of Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm. Bass and Redford were good friends, colleagues say.

All of which means we’re ending with the beginning. See what we did there? So much for starting at the beginning and following chronologies.

And, yes, it’s still all about people.