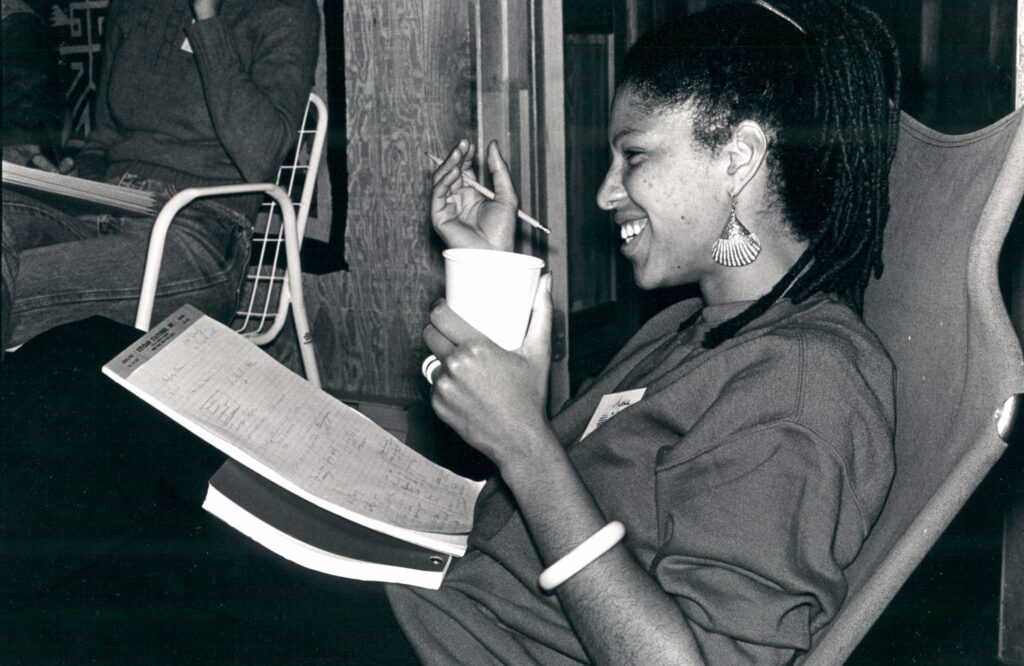

“Alma’s Rainbow” [working title was “Violette (Balancing Dreams)”] being developed in the 1984 Directors Lab.

by Aramide Tinubu

Well into the 21st century, Hollywood remains almost entirely white and mostly male — like most major industries in America. Women and people of color, specifically Black people, have undoubtedly made strides in various divisions, including acting, filmmaking, and countless other aspects of storytelling. Yet, seeing the contribution of Black women in the film industry requires cinema lovers to look a little bit more closely at what’s hidden beneath the apparent glittering surface of Hollywood and seek out that varied films and projects Black women have contributed to the medium.Taking a closer look will reveal just how the industry has continually stalled and shut out Black women filmmakers despite the quality of their work.

Three years after Julie Dash became the first Black woman to have a full-length theatrical release in the U.S. with Daughters of the Dust (1991 Sundance Film Festival premiere), Sundance Labs alum Ayoka Chenzira debuted her glittering coming-of-age drama, Alma’s Rainbow. Alma’s Rainbow is a mother/daughter love story that encompasses what it means to be on the precipice of womanhood. Set in the ’90s in Brooklyn, the film follows Rainbow Gold (Victoria Gabrielle Platt), a vivacious teenager who lives with her strict beauty-salon owner mother, Alma Gold (Kim Weston-Moran). A single mother who has always had a tight leash on her child, Alma’s influence over Rainbow begins to wane when her glamorous sister Ruby (Mizan Kirby) comes gliding back to town from an extended stay overseas in Paris.

Immediately enamored with her aunt, Rainbow begins to see womanhood from a different perspective. However, Rainbow’s awakening frightens Alma to her core. Alma’s Rainbow emerged when there was a renewed interest in Black life in Hollywood. However, that focus was primarily on Black men. Since Rainbow’s concerns were about boys, being seen by her mother, and valuing herself as a young Black woman, the film was dismissed. Instead, Hollywood favored grittier male-dominated stories like John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991) and the Hughes Brothers’ Menace II Society (1993).

“Some of the distributors had questions and comments because they had not experienced these characters or knew of a Black woman owning a beautiful home,” Chenzira told Shadow and Act. “Therefore, it could not exist. So there is this assumption of the all-knowing distributor, marketer, or PR person who seemed very unwilling to go on this different kind of journey at that time. [Alma’s Rainbow’s] lack of distribution told me more about the business and the people in the business than anything else.”

Alma’s Rainbow did not receive a theatrical release until 2022. Some three decades later, we stand in an era that has just this year spawned powerful, critically acclaimed films like Sundance alum Gina Prince-Bythewood’s The Woman King and Chinonye Chukwu’s Till. Yet, these films — and the Black women who gave years of their hearts, time, and labor to make them — are still being shut out of award spaces that claim inclusivity and diversity.

Set in the 19th century in the West African Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin), Prince-Bythewood’s historical drama, The Woman King, follows the fearsome General Nanisca (Viola Davis) and her all-female army, the Agojie. These warrior women have been tasked with keeping their empire safe from a rival kingdom and combating the horrors of the slave trade. Though the film is a thrilling action piece, the heart of the movie centers on the strength of Black sisterhood. Through her bond with her lieutenants, Amenza (Sheila Atim) and Izogie (Lashana Lynch), and a precocious recruit, Nawi (Thuso Mbedu), Nanisca and the women surrounding her learn to define strength and beauty for themselves. The film is a love letter to Black women, and Davis was just nominated for a Screen Actor’s Guild award, but was shut out of the Oscars Best Actress race.

Though it’s a very different example of the power of Black women, Danielle Deadwyler’s portrayal of Mamie Till-Mobley in Chukwu’s Till is searing. The film recalls the horrific murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till, who was killed in Money, Mississippi, in 1955. Though Emmett’s death is the film’s catalyst, his mother, Mamie, whose pain and strength helped spark the Civil Rights Movement, stands at the heart of this narrative. More than a historical drama, Till is a damning examination of continued white American violence against Black bodies and the anguish and terror of Black mothers who are left to pick up the pieces. Deadwyler’s performance was also recognized with a SAG award nomination this year, but not an Oscar nom.

Like The Woman King and Till, Alice Diop’s Saint Omer, which was also ignored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, is a story of Black motherhood. Based on a true story of infanticide, Saint Omer follows Rama (Kayije Kagame), a pregnant researcher who begins attending the trial of a young woman, Laurence (Guslagie Malanga), who is on trial for killing her baby daughter. The film examines the overwhelm of motherhood and the madness of racial trauma. Like the previously mentioned films, Diop places the nuances of Black womanhood at the center of her story. The Academy’s choice to ignore the quality and greatness of these films, just as Hollywood did with Alma’s Rainbow three decades ago, sends the message that these movies hold little merit within the industry.

For centuries, Black and brown people have flocked to the cinema enthralled with films like The Wizard of Oz, Titanic, and countless others where no one person of color appears on the screen. Yet, the stories and the characters have captivated and inspired us. To ask white people to do that for movies centered on Black women is apparently far too tall a task.

“We, Black women, do not get that same grace,” Prince-Bythewood writes in The Hollywood Reporter earlier this month. “So the question we need to ask is, “Why is it so hard to relate to the work of your Black peers?” What is this inability of Academy voters to see Black women, and their humanity, and their heroism, as relatable to themselves?”

It is not simply that white moviegoers refuse to connect with Black characters. In dismissing the films altogether, they deny Black humanity, perpetuating the cycle of erasure, racism, and contempt for our stories and history. Lack of recognition also bars Black people from positions of power in spaces like Hollywood, continually forcing us to toil against closed doors and glass ceilings.

Black women directors proved themselves and their stories “worthy” of representation decades ago. However, they continue to face an uphill battle. In the early 2000s, hardly any Black women filmmakers had films released at a major studio. Some twenty years later, directors like Prince-Bythewood, Chukwu, Ava DuVernay, Nia DaCosta, Numa Perrier, and many others have contributed to the cinema canon, but Hollywood continues to move the goalpost for the accolades they so richly deserve.