By Vanessa Zimmer

A single Māori mother who saw inequities in New Zealand, who had experienced oppression, racism, and sexism, Merata Mita (1942–2010) picked up a camera to speak for her people. She had no formal film training and she didn’t invent new techniques. She simply told the stories.

In the process, she emerged at the forefront of Indigenous cinema, both in her native country and internationally. She remains the first and only Māori woman to write and direct a feature film — 1988’s Mauri, a love story exploring cultural differences and tensions in her homeland. Mita spread her community-centered style of storytelling as an advisor and artistic director of the Sundance Institute’s Native Lab between 2000 and 2009. In 2016, the Institute created the annual Merata Mita Fellowship in her honor.

Instilled from a young age with the history of her tribe, an identity that gave her strength and security, Mita originally followed her heart as an activist for the Māori (and also for women). “What underscores our culture is who we are and where we come from,” Mita said in a 1997 interview on Hawai’i Public Television. “Our elders say that, unless we know that, we’ve got nowhere to go in the world.”

She was among the nonviolent protesters at Bastion Point in Auckland, where natives challenged the takeover of traditional Māori lands. They occupied the land for 507 days. On the 506th, one of the occupation leaders told Mita the army and police were coming to remove them and someone needed to record the proceedings. Mita somehow scrounged up a camera. “Overnight, I became a filmmaker,” she muses in the public television interview.

She converted the footage into the short 1980 documentary Bastion Point: Day 507. Years later, the Māori got their land back. “I still haven’t gotten over the bewilderment of finding myself being part of this area (filmmaking) that I didn’t choose to be in,” she said. “It was chosen for me.”

Still, in a way, filmmaking was a logical leap. She grew up surrounded by oral storytelling traditions. And: “Film is very close to oral tradition.”

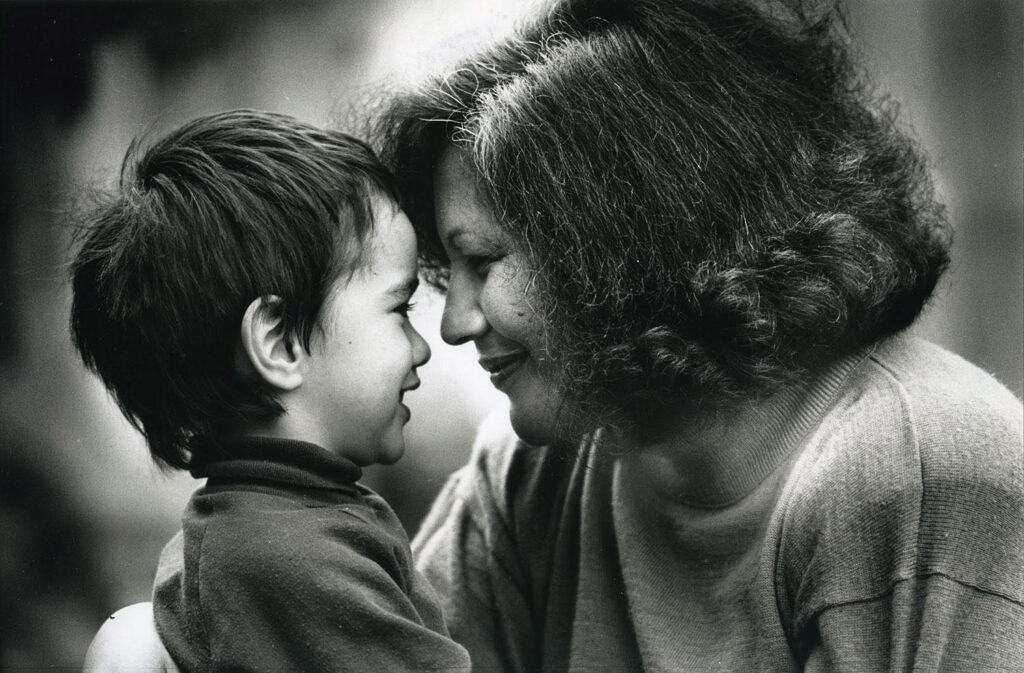

Youngest son Hepi, who made the 2019 Sundance Film Festival’s Merata: How Mum Decolonized the Screen, has recalled his mother often saying that being born Indigenous is itself a political statement. She also spoke of the imperative of investing in her children’s future.

Mita’s children helped her film at protests and served as crew. Their mother fervently believed the Māori — and the Indigenous in every country — should tell their own stories. That’s what it means to decolonize the screen.

One of Mita’s landmark documentaries, 1983’s Patu!, reflected the overwhelming native opposition to South Africa’s rugby tour of New Zealand in 1981, which resulted in violent clashes between anti-apartheid protestors and the police.

“Mita unflinchingly captured brutal racism and police violence, even as she was also experiencing them in private,” according to a 2019 British Film Institute article covering Hepi’s film. “Her older sons remember police raids with dogs on their family house while she was shooting; they were beaten and their mother was strip-searched. When the footage was in the can, the police tried to remand it as evidence. ‘We called it evidence, too, but of police brutality,’ her son Richard tells his younger brother behind the camera.”

In recorded interviews, Mita comes across as well-spoken and calmly earnest. “To me, the truth has always been radical,” she reasoned on public television. At the Sundance Institute, the New Zealander struck Adam Piron (present-day director of the Sundance Institute’s Indigenous Program) as a loving person with a warm energy, sort of like an aunt. She exhibited a “tough love” approach to new filmmakers, he says, a level of scrutiny that inevitably made their work better.

The Mita style followed an “Indigenous mind-set,” says Piron in a Zoom interview — a collective view implying a responsibility to the community. Piron considers her a mentor, but: “Her legacy extends beyond those who knew her.” She inspired others regarding Indigenous storytelling around the world.

When the Institute created the Merata Mita Fellowship for Indigenous filmmakers in 2016, Bird Runningwater, Piron’s predecessor, made a point of emphasizing Mita’s impact. “Throughout her career, she identified the lack of training for Māori people in the New Zealand film and television industry and, therefore, an underrepresentation of her community’s stories,” he said. “Merata dedicated her life to addressing these areas. She was a global advocate for Indigenous voices and we are proud to continue her efforts through this new fellowship.”

The fellowship has been awarded annually since then. In 2020, Leya Hale, of the Dakota and Diné nations, received the fellowship and lamented that she’d never met Mita, who left behind a wealth of wisdom and lessons for filmmakers. But she said she watched Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen at least 15 times.

“Every time I watched it, I found something new and inspiring that she said. One of the sound bites that really resonated with me was when someone asked her, ‘Why don’t you make nice films?’ Her response was, ‘I can’t make nice films because they’re doing ugly things to my people.’ ”

“Those words really meant a lot to me. Sometimes, as a filmmaker, we have to tell hard stories,” said Hale, who was working on a project addressing the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women. “So her words comfort me and give me strength to tell some of these tough stories that are happening in our communities.”

Just like Merata Mita would have wanted.

Give Me the Backstory: Get to Know Mathias Broe, the Director Behind “Sauna”

By Jessica Herndon One of the most exciting things about the Sundance Film Festival is having a front-row seat for the bright future of independent

Give Me the Backstory: Get to Know Shoshannah Stern, the Director of “Marlee Matlin: Not Alone Anymore”

By Jessica Herndon One of the most exciting things about the Sundance Film Festival is having a front-row seat for the bright future of independent

Give Me the Backstory: Get to Know Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez, the Co-Directors of “Sujo”

By Jessica Herndon One of the most exciting things about the Sundance Film Festival is having a front-row seat for the bright future of independent