By Vanessa Zimmer

For Waldo Salt, writing a screenplay wasn’t about crafting a clever or witty piece of dialogue — although he could certainly do that. It was about writing in images, almost like composing poetry.

That’s not too surprising, considering he wrote the powerful scripts for Midnight Cowboy (1969) and Coming Home (1978), both of which won him Oscars, as well as Serpico (1973) and many others. His legacy — he died in 1987 — is recognized with the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award, presented every year since 1991 at the Sundance Film Festival.

His was not a legacy easily won, as told in Waldo Salt: A Screenwriter’s Journey, which played at the 1990 Festival. Unlike so many others, Salt returned successfully to the film industry following an 11-year absence after being blacklisted for belonging to the Communist Party during the McCarthy witch hunts of the 1950s. During that absence, he kept afloat by writing under a pseudonym, outside the hub of the industry, mostly for television and commercials.

He had debuted in 1938 at just 24 years of age with the screenplay for Shopworn Angel, with Jimmy Stewart and Margaret Sullavan, and followed with a bevy of projects, including Rachel and the Stranger, with Loretta Young, Robert Mitchum and William Holden, and The Flame and the Arrow, with Burt Lancaster and Virginia Mayo.

The blacklist experience profoundly affected his life, according to the documentary, endowing him the interest and introspection to develop characters rejected by society as outsiders, who were stubborn and eccentric, and who dared to suggest that the American dream was not perfect.

As John Schlesinger, the director of Midnight Cowboy, put it: Salt took his anger and turned it into wisdom. Midnight Cowboy is the story of the relationship built on the streets of New York City between a wannabe street hustler from Texas (Jon Voight) and an ailing con man (Dustin Hoffman).

“

I ended up at 50, over the hill, thinking I had no future

Waldo Salt

A major theme for Salt was the idea of family and home, and being separated from family and home, added Voight, who also starred as a paralyzed Vietnam veteran in Coming Home. “I think he understood that real well, that loneliness.”

The loneliness started with a difficult childhood, according to the documentary, with a right-wing extremist father and a suicidal mother. Salt’s mother would transform every Christmas into one “replete with terror,” said narrator Peter Coyote, by writing a suicide note to the family.

Salt belonged to the Communist Party for 18 years — daughter (and actress) Jennifer Salt believes he was driven in part by a longing for family, as well as a moralistic bent to make a better world. But he lost faith after a famous 1956 Khrushchev speech that revealed atrocities committed by Stalin.

Leaving the party left him further adrift, at one point losing trust in his ability to write. The first three films he wrote under his own name after returning to the industry were horrible, Salt jokes in the documentary, more damaging to his career than being blacklisted. He was living in a cheap room, sick with pneumonia, always feeling like the underdog: “I ended up at 50, over the hill, thinking I had no future,” he says.

Then he had an epiphany: No one else was to blame. He was to blame. He decided he needed to write better. “I think it’s a lesson for all of us, for writers, that we have got to allow ourselves to write as well as we possibly can.”

He recommitted to the work, to understanding fully and creating vivid images with his words. For Coming Home, for example, he talked to hundreds of Vietnam vets, winding up with 5,000 pages of transcripts.

“

When an independent film is made that breaks ground, whether in technique or content, it opens up a new field in subject matter

Waldo Salt

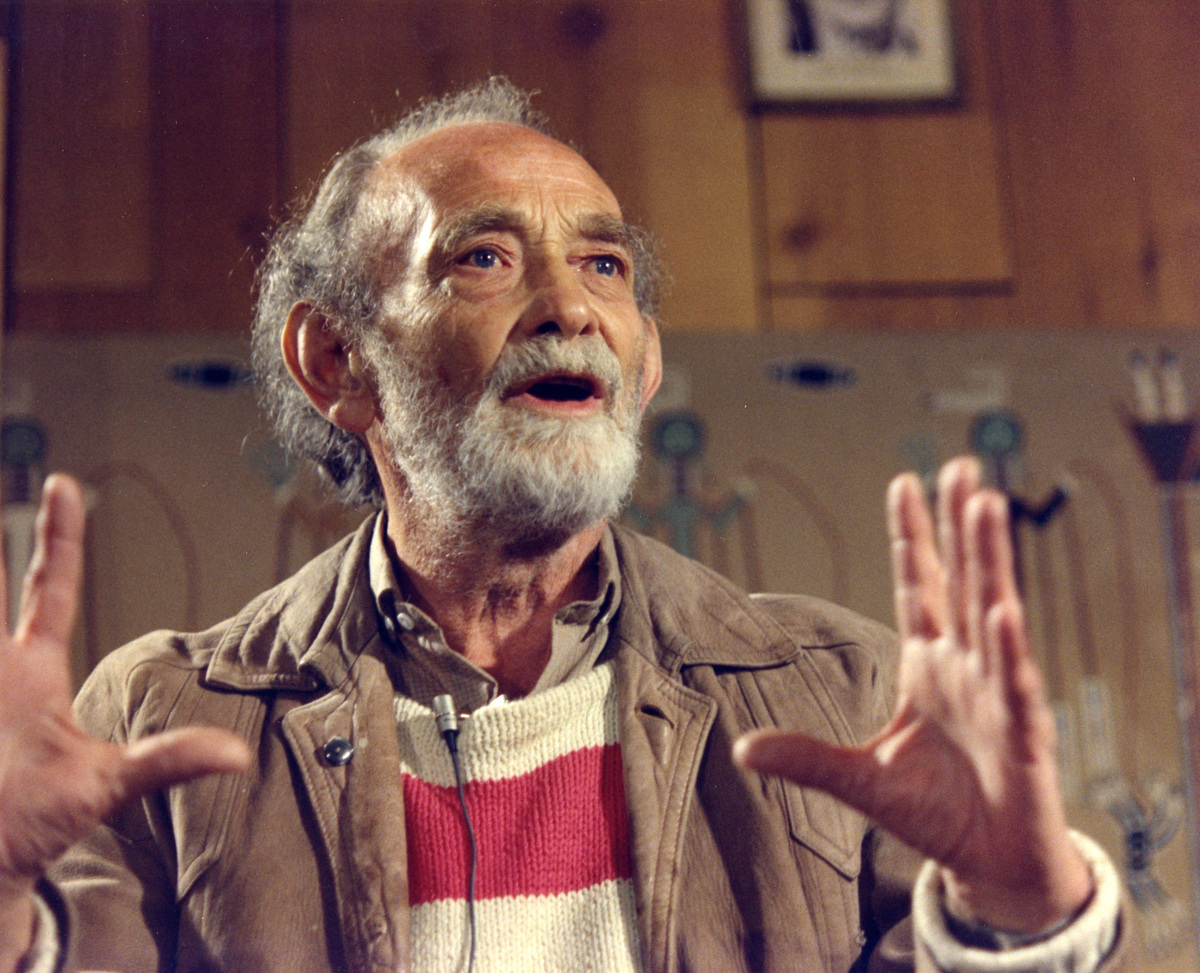

Salt was a slight man, with a crop of curly hair, and somewhat prominent ears. Jerome Hellman, producer of Midnight Cowboy, was always taken by Salt’s ears, which he described as tilted slightly forward. “Subsequently, I got to feel that’s why Waldo heard so much and absorbed so much information.”

Salt wouldn’t likely be insulted by Hellman’s observation. The screenwriter greatly appreciated humor. Comedy, he said, is the camouflage we all turn to as we cover up what’s really going on.

In the 1980s, Salt served as a creative advisor in multiple Sundance Institute Labs for directors and screenwriters, sharing his expertise with emerging filmmakers. He was inspired by the labs, he said in a 1983 video shot at the Sundance Resort in Utah: It frees up the imagination, he said: “It gives a rebirth to the industry, which I think has fallen on bad days.”

Ever the maverick, he objected to the commercial nature of the business at the time, which put movies “in the hands of people who have no interest or knowledge of making film.” He praised independent film: “When an independent film is made that breaks ground, whether in technique or content, it opens up a new field in subject matter,” he said.

Whereas commercial films are made in pursuit of money, “independent film is developed out of a need or passion.”

About six months before he died, Waldo Salt received the highest honor bestowed by the Writers Guild, the Laurel Award for Screen Achievement.

For a list of winners of the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award, click here.