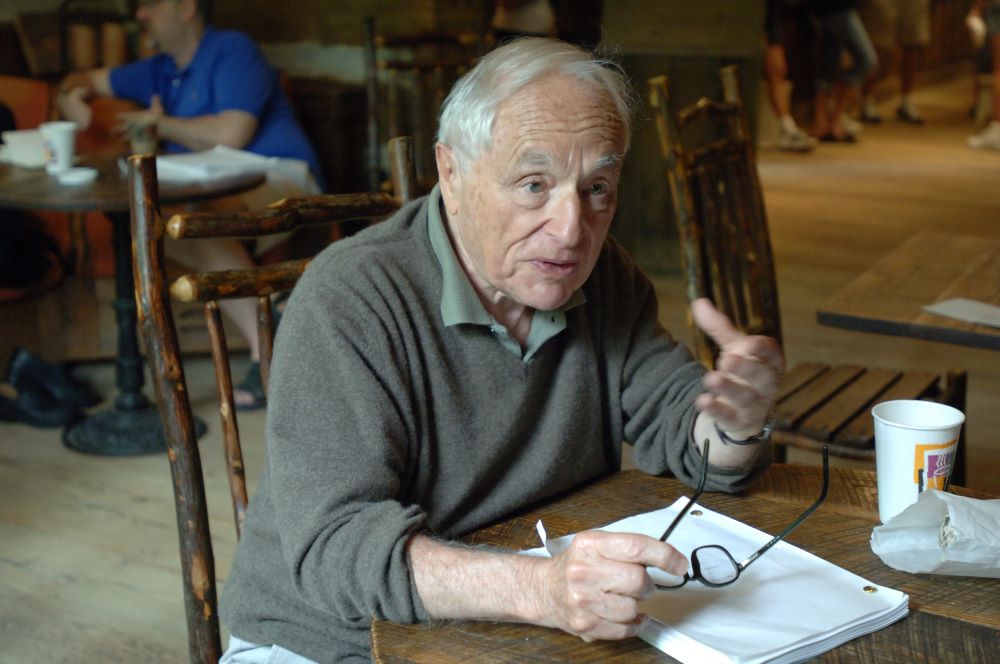

Walter Bernstein participated as an advisor at the 2005 Directors Lab at the Sundance Institute. He served as an advisor at the Sundance Labs for 25 years. (Photo by Fred Hayes)

By Vanessa Zimmer

Once upon a time in 1950s America, Walter Bernstein dared not sign his name to his screenplays.

Those were the now-surreal days of red hysteria, when actors, entertainers, and others who worked in film and television were blacklisted for leftist sympathies and denied jobs by the big studios.

Bernstein came through somehow without bitterness, reclaimed his career writing scripts, and took to mentoring young writers at the Sundance Institute. He even had a screenwriting fellowship named after him at the Institute starting in 2019.

“Erudite, political, and fearless, Walter’s words always mattered; his stories mattered and his truth mattered,” wrote Michelle Satter, the Institute’s founding senior director of artist programs, in a tribute to Bernstein after his death in 2021. “Walter was a powerful presence at the Sundance Institute’s Screenwriters Lab for over 25 years, and he made an extraordinary impact on the work of independent filmmakers and the stories they told, bearing witness and challenging the world we live in.”

But Bernstein struggled to live and to make a living for a decade during the witch hunt that was Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare.

Former associates walked across the street to avoid him. FBI agents followed him and rifled through his trash. He lived for a time with also-blacklisted actor-director Martin Ritt and his wife, recounted Bernstein to fellow screenwriter Doug McGrath at a Sundance Institute event in 2013 — Ritt using his prowess as a gambler in poker and on sports competitions to support them all. Like others in his situation, Bernstein took to using a pseudonym, eventually hiring a “front” who could meet in person with executives so Bernstein could continue writing for film and television.

Bernstein said it was true he leaned left politically. He joined the Young Communists while attending Dartmouth College, and he later joined the American Communist Party for a few years after fighting for the U.S. and serving as a war correspondent during World War II. He wasn’t looking to sabotage his country or overthrow it by violence, he said in an interview in the July-August 2021 issue of Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. He just thought socialism had some good ideas about equality and brotherhood, certainly better than the rising fascism he saw in pre-war Europe.

The unfairness of the blacklisting was striking: Could a man be punished for what he believes? Do thoughts make one disloyal? Even if one served as a soldier and a journalist lauded for his coverage of GIs? “Speech was now punishable,” Bernstein wrote in retrospect, as quoted in the Dartmouth article. “You did not have to do anything, you had only to advocate.”

Perhaps one of Bernstein’s most important scripts was for The Front (1976), based on his own experiences on the blacklist and directed by Ritt. Bernstein originally approached the story as a straight drama about an individual on the blacklist, but he and Ritt couldn’t get anyone interested.

“I had always wanted to do a comedy. Humor was very much a part of me,” Bernstein said in a 1997 interview with Patrick McGilligan for the book Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 60s. He got the idea of writing it as a dark comedy, with the front as the focus.

“And I felt we were able to make the points that we wanted to make,” he said to McGrath in 2013. “The political points were made, and in a much more audience-friendly way.” The screenplay was nominated for an Oscar.

“We screened the award-winning film The Front multiple times, and it was very powerful to hear how Walter’s personal story was the inspiration for the film,” wrote Satter in her tribute. “And for all the writers, often too young to really know the devastation of the blacklist, for them to understand the privilege of devoting a life to writing, free expression, and, of course, using your real name, this would be an unforgettable evening.”

Continually captivated by political issues — he left the American Communist Party in 1956, after the Soviet Union invaded Hungary — Bernstein also wrote Paris Blues (1961, co-written with Jack Scher and Irene Kamp), on American expatriates and racial tolerance in Paris and starring Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman; Fail Safe (1964), about an accidental nuclear crisis; and The Molly Maguires (1970), about Irish American coal miners fighting union busting and starring Sean Connery in a sympathetic role. Not-so-political films included Semi-Tough (1977), which spoofed New Age movements of the 1970s and starred Burt Reynolds and Kris Kristofferson, and Yanks (1979, co-written with Colin Welland), about American soldiers in the U.K. during World War II, with Richard Gere and Vanessa Redgrave.

The prolific Bernstein also wrote for television, including the scripts for the Emmy-winning Miss Evers’ Boys (1997), based on the true story of the U.S. government using Black men for syphilis research, and Hidden (2011), a crime drama miniseries.

He worked well into his 90s. “It was like watching a woodpecker in heat,” said Bernstein’s son Nick in the Dartmouth article. “Writing was his life force.” Bernstein died of pneumonia at age 101.

Bernstein held dear his memories of the camaraderie during the blacklist period, when writers helped and shared work with one another. His obituary printed in The New York Times recalls Bernstein’s thoughts on that time: “I look back on that period with some fondness in a way, in terms of relationships and support and friendships. We helped each other during that period. And in a dog-eat-dog business, it was quite rare.”

Past recipients of the Walter Bernstein Screenwriting Fellowship include Dina Amer in 2022 (Cain and Abel), Erica Tremblay and Miciana Alise in 2021 (Fancy Dance), and A.V. Rockwell in 2019 (A Thousand and One).